In the digital age, even the death of a pope becomes content From “Conclave” streaming boom to memes to conspiracies, the Internet loves the Vatican

Within a few hours of Pope Francis's death on April 21, 2025, the global reaction was not one of collective mourning or silent spiritual reflection, but a cultural phenomenon fully immersed in the digital ecosystem. Symbolically marking this shift was the boom of Conclave, the 2024 Oscar-winning film for Best Adapted Screenplay, which saw a 283% increase in views on Prime Video on the day of the Pope's passing. A spike that turned the film into a viral hit and made the Vatican a global trending topic. Cinema has long held a deep fascination with the rites, mysteries, and contradictions of the Holy See. From esoteric thrillers like Angels & Demons to the melancholic irony of Habemus Papam, and the decadent pop aesthetic of Sorrentino's The Young Pope, the Vatican has always been imagined as a stage for power, intrigue, and contrasts. But Conclave succeeded where others had, to varying degrees, failed: the film became a viral phenomenon for online cinephiles, whose edits and ironic slang turned the process of choosing a new pope into something akin to a RuPaul's Drag Race competition—celebrated yet reduced to entertainment, spread through heavy trivialization. Essentially, the film gave the Church the allure of Game of Thrones, though many viewed its message as somewhat anti-Catholic. Nevertheless, its success laid the groundwork for the virality that the news of Pope Francis’s death would reach online—at a time when the death of the Pope, in short, became content. And as such, it was immediately absorbed, reinterpreted, and reposted on social media: in a full-fledged “commemorative post competition”, dozens of celebrities—from actors to singers, from politicians to influencers—shared photos with Francis, many taken years earlier. The tone often felt more promotional than spiritual, as if the real grief expressed was over the missed opportunity for a selfie with the pontiff.

@otiyato Grant us a Pope who doubts. #conclave #popefrancis #catholic #filmtok #fyp #fypシ゚ #radiohead #cinephile original sound - otiyato

Upon the news of the Pope's death, conversation on X (formerly Twitter) took a darker and more surreal turn. Conspiracy theorists scrutinized every frame of the images showing the Pope’s body on display at St. Peter’s, searching for “signs” and hidden details. The prophecy of the “Black Pope” resurfaced, with hundreds of threads attempting to prove the next pontiff would be an apocalyptic figure. The succession process was discussed with the same language used for a reality show: “Who will be the next Pope?”, “The favorites of the conclave”, “What the bookmakers say”. Strange bots, likely deployed by some shadowy foreign force aiming to destabilize public trust in the Church (already low, though it had risen significantly during Francis’s papacy), circulated videos of a hooded Easter procession, claiming with a very American naivety—lacking a clear understanding of European history—that there was something deeply sinister about these rituals. The reappearance of former bishop and now-excommunicated Carlo Maria Viganò, a favorite among conspiracy fans, QAnon, and Pizzagate believers, did not go unnoticed. In less concerning corners of the Internet, likely cardinals were discussed as “contenders” in a show or competition—yet another unfortunate but effective attempt to strip meaning and seriousness from a solemn and important process, with people even starting betting pools and reinventing themselves as Catholicism experts after spending two hours or less on Wikipedia.

Users, both large and small, turned Pope Francis’s death into an excuse for newsletters, retrospectives, praise for progressivism, and accusations of traditionalism. Others mocked these attitudes with memes, adding commentary and analysis to commentary and analysis—but essentially reaffirming that at the center of all this talk there wasn’t truly a matter of faith, but rather pure, morbid media curiosity. It seems the entire Internet pounced on the sad event of the Pope’s death to squeeze out interactions and views. Amidst this chaos of fake news, political interpretations (balanced or not), and cries of “pick me” from every corner of the web, the genuinely religious dimension—belonging to those who saw the Pope not as a public figure but as a spiritual leader—was largely sidelined. Even the New York Times coverage seemed less inspired than the forecasts about the next Pontiff, or the explainers about how a conclave works, and so on. It’s unlikely the world rediscovered its Catholic roots overnight—more likely, every media outlet in the world, as well as every media personality on this side of the planet, saw in the Pope’s death, carried by the viral wave of Conclave, a generous well of engagement to draw from freely.

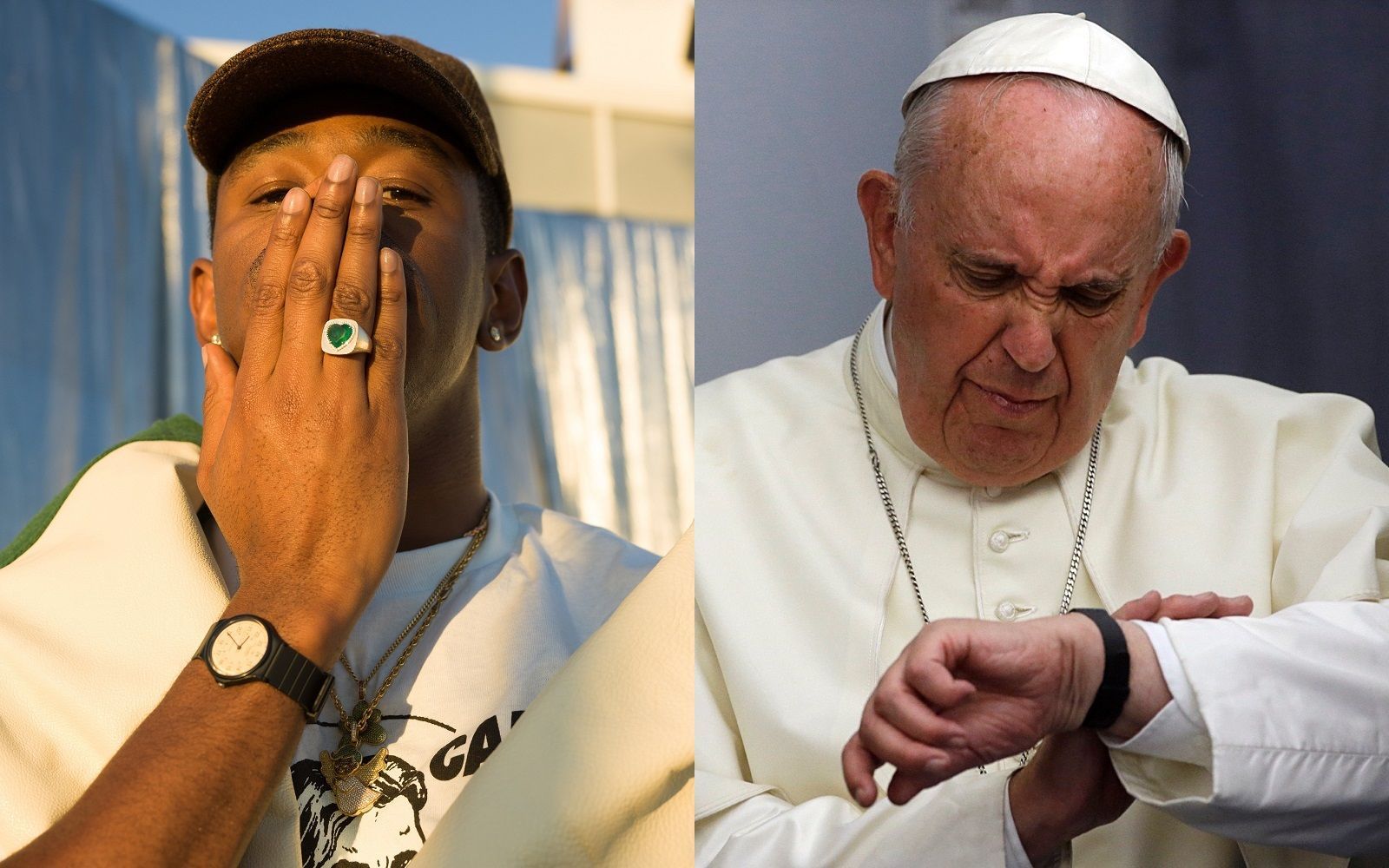

One of the images of Pope Francis that will always be remembered is this one:

— Today In History (@historigins) April 21, 2025

Crossing St. Peter's Square alone, empty due to the pandemic, in the rain and silence. No words were needed to capture the moment. pic.twitter.com/1McjEH0e32

And then there was the J.D. Vance case, Vice President of the United States, who had met with Pope Francis just hours before his death. That alone was enough to spark the most absurd and viral meme of the week: “J.D. Vance killed the Pope.” A theory as grotesque as it was irresistible to Internet logic, which turned it into a festival of dark humor: from memes depicting him as the Antichrist to jokes about how every visit he makes causes a catastrophe. In this case, the digital world didn’t just report the news: it manipulated it, reinterpreted it, made it go viral and finally turned it into entertainment. The death of a Pope in 2025 is not (only) a religious or political event, but a complete, accelerated, participatory narrative cycle, and above all, fully postmodern. It’s the first time such a phenomenon has occurred: Benedict XVI died after abdicating, and John Paul II died too early. Meanwhile, social media has evolved to give rise to streams of folkloric and neo-mythological narratives, Christian fanatics (Catholic and otherwise) have emerged on the Internet in all their alarming frenzy, and even the Trump government established a “Faith Office” led by televangelist Paula White, engaged in the most bizarre displays of idolatry and political-religious collusion seen since the Lateran Pacts. In any case, however useful religion may be as an “instrumentum regni,” Trump spent his Easter Sunday playing golf and not in church—not that his followers seem to care.

From official tributes to shitposts, from theological commentary to live reactions, every phase of the Pope’s death was documented, commented on, and remixed. What Conclave portrayed as fiction has now become amplified reality: an ancient ritual, steeped in solemnity and mystery, watched and distorted through the lens of our time—where even the most sacred moment can go viral, and every prayer can look like a post, and every coincidence the next meme to repost. Yet we are reflecting less on who the next Pope will be—likely to be appointed by May—about whom bots on X have already begun spreading misinformation, and where showdowns between the Church’s progressive and ultra-conservative factions are expected.