Is rap still for 'real men' only? The parabole of Drake and Andrew Tate

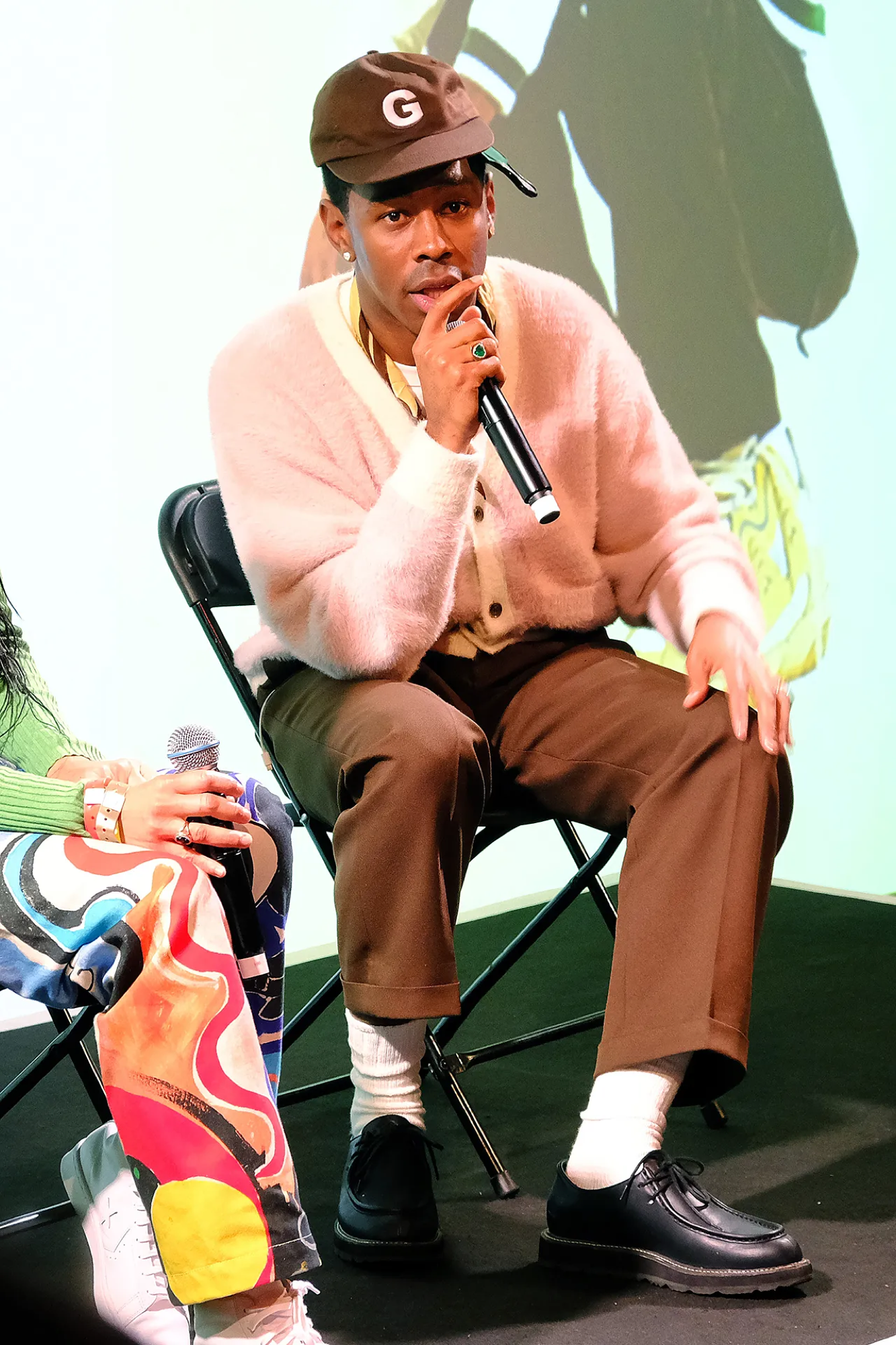

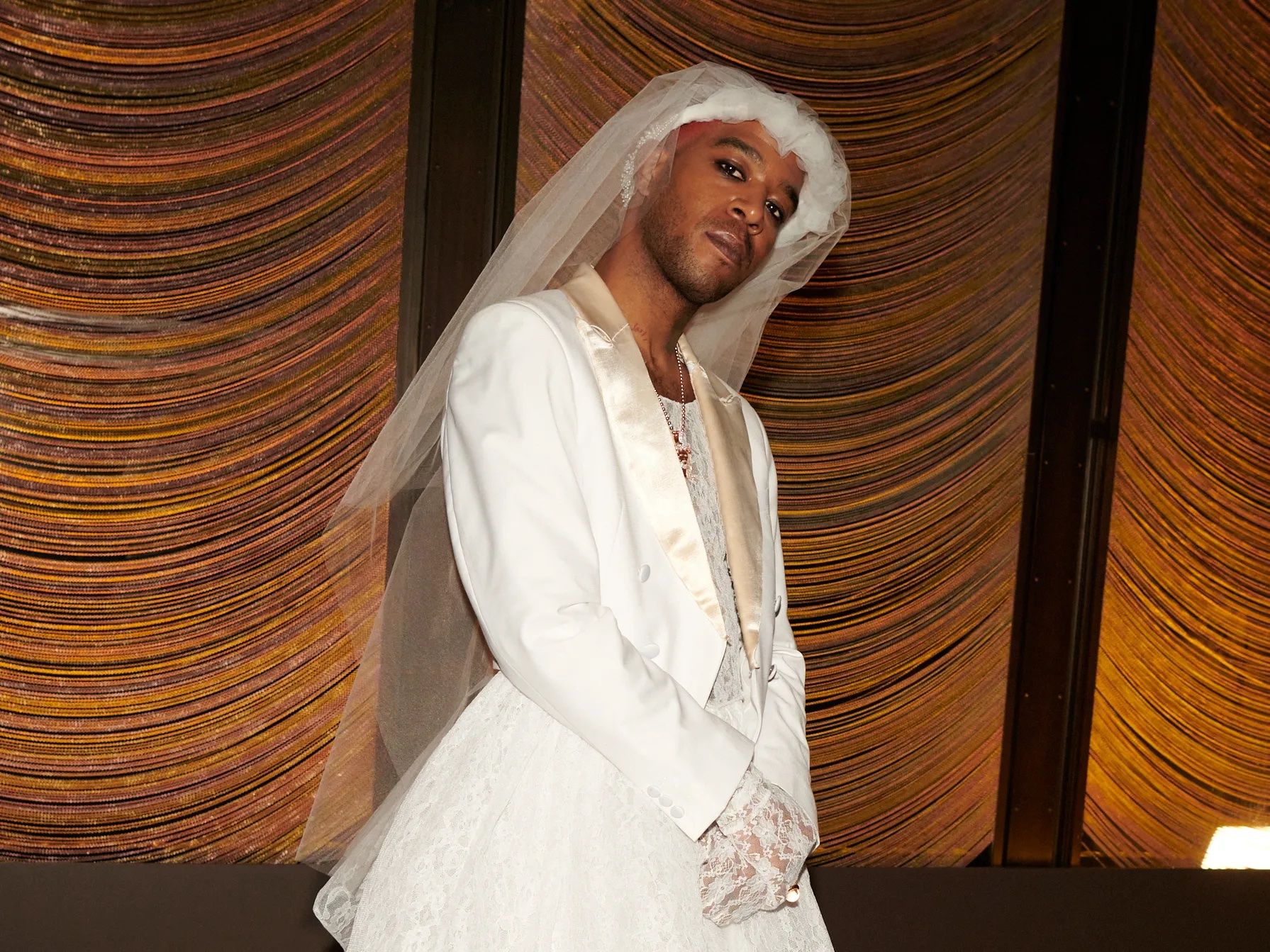

Among the most famous tropes of the music world is surely that of the rapper, a type of artist who for social, historical and cultural reasons has conventionally been associated with a tough, rude, masculine, sometimes gangster, but above all virile personality. Considering that the rap world has long since tried to shake off these connotations, shining a spotlight on this topic does not carry any positive omens. Recently, an old diatribe involving Andrew Tate and Drake has returned to hit the headlines, opening up a previously archived debate. In an episode of his podcast Tate Speech, the host threw a dig at the Canadian rapper, stating: «Imagine being Canadian. Imagine saying, "I'm a man." From where? "From Canada." What? That doesn't fit, what are you talking about? Wait, you're a man? From Canada? No, it can't be. "No, no, I'm a man." No, you're not, dude, of course you're not. There are no men in Canada. You're kidding.» In recent years, artists such as Tyler, The Creator, Brockhampton and Frank Ocean have rewritten the history of hip hop music by expanding its themes and pushing the genre beyond stories about sex, drugs and crime, but given the strong traction of Tate's thinking online, a herald of toxic masculinity with 8 million followers, it raises the question of whether the rap scene is still a victim and creator of a chauvinist view of manhood.

Andrew Tate's attack on Drake

Theres a reason I deny meeting all the famous people who try to meet me. https://t.co/zMVaGkmchY

— Andrew Tate (@Cobratate) July 4, 2023

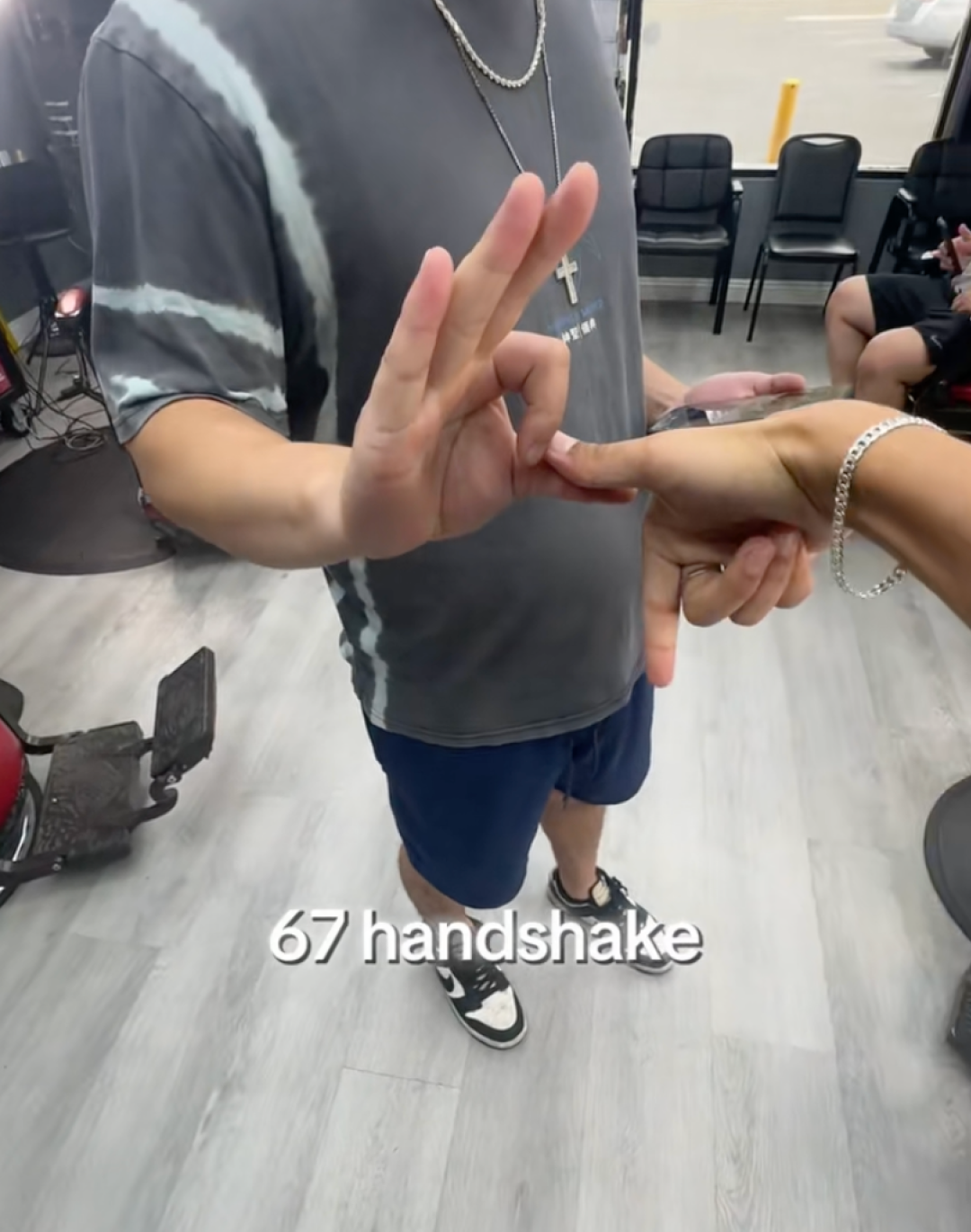

Andrew Tate's affront to Drake has a precedent dating back to this summer, specifically to the days before the rapper's It's All a Blur tour began. For the occasion, Drake had a pink manicure done, and posted the end result on social media. The shots made the rounds on all platforms, X (first Twitter) included, thanks to a repost by Tate who commented on the artist's stylistic choice with the caption: «There's a reason I refuse to meet all the famous people who try to meet me.» Judging by the responses, Drake doesn't seem to have been too upset by the heteronormative inferences of the former kickboxer - now being investigated for sex trafficking. Despite the fact that Tate's is a meme-character that one can take seriously with great difficulty, his words must still be measured, because despite being incredibly retrograde, they continue to influence a considerable number of listeners, often very young ones.

How has the image of rappers changed?

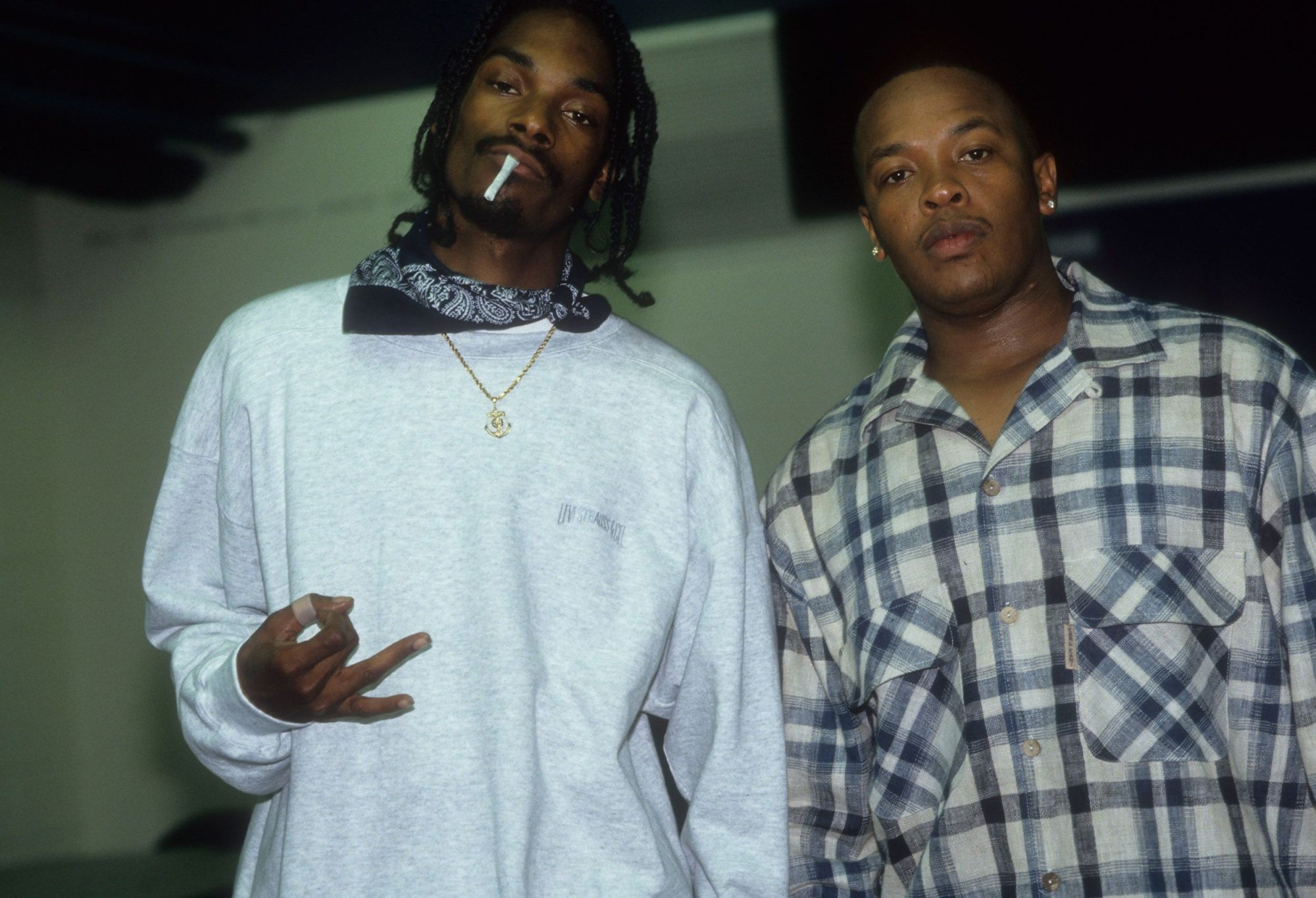

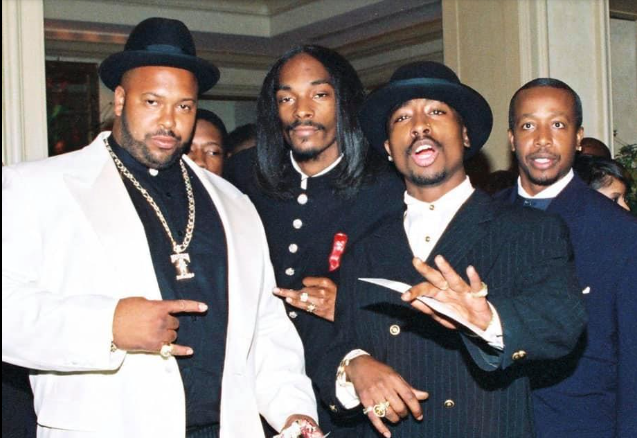

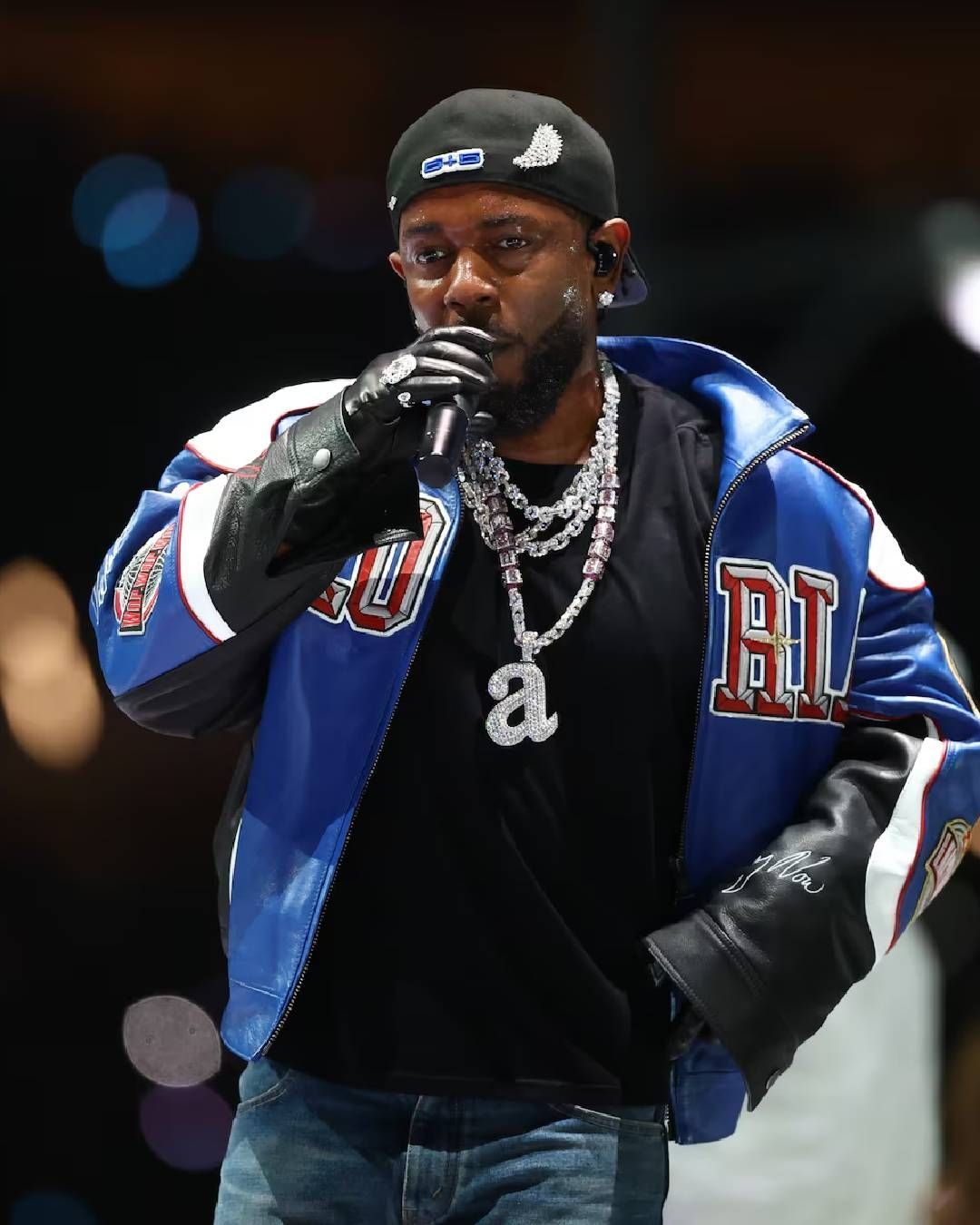

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, artists such as 50Cent, B.I.G., Dr. Dre and Snoop Dog painted a well-defined image of rap in the imagination of their listeners, triggered by songs centred on street crime, but a specific aspect of their thematic choices reveals their motives. Although many after them tried to imitate their style, evoking their own imagery out of goliardia rather than art, the ultimate aim of 90s rap was not to incite fans to hatred, violence against women or drug use, but rather to narrate their everyday stories. Evidence of this was the discography of 2Pac, a progressive artist, active for women and justice, who nevertheless used to expound on the most disparate themes, also related to a life of transgression and danger. For a long time, fans and the very young confused songs about murder or disrespect for women with rap songs as verses to be inspired by, but now this world has only remained in the hands of the likes of Tate, while real rap artists have preferred to favour a paradigm shift.

2017, a year in which hip hop saw the release of projects such as BROCKHAMPTON's Saturation II and Tyler, The Creator's Flower Boy, was not enough to make rap lovers realise the genre's cultural shift towards a conscious and contemporary openness, far removed from misogyny and transgression. In 911 / Mr. Lonely, featuring Frank Ocean and Steve Lacy, Tyler tackles the theme of loneliness, in Boredom he offers an even more vulnerable view of himself by recounting how boredom devours his days, while in the track SORRY NOT SORRY, released this year as a single from CALL ME IF YOU GET LOST: The Estate Sale, the rapper has produced a song that allows the listener to take a closer look at his introspection and self-reflections addressing sensitive issues, from the injustices suffered by the Black community to the invasion of privacy. Adding to these examples also that of Kid Cudi, who with 2009's Man on The Moon paved the way for the narration of dynamics that are soft in terms of terminology, but hard in terms of the delicacy of the subject matter, it is really hard to believe that the intense work of many artists has failed to change the minds and perceptions of many listeners. Yet, if the aforementioned Tyler, The Creator has managed to be credible in the eyes of his fandom by going from appearing as a 'cockroach-eating' misogynist to being the emblem of the metrosexual rapper, why are there still those who create controversy in the face of a Drake who wears pink nail polish? One of the answers we can give to this seemingly nonsensical question lies in the communication of Drake's self-image.

Far from being a justification for the words spoken by Tate in recent months, if Tyler has received fewer attacks from men like Tate than his Canadian colleague, there must be a reason. The sudden change in Drake's musical and personal style may have shocked his fans with the release of the 2022 house album Honestly, Nevermind. At the time, the record accentuated and exacerbated criticism from those who claim to want «the old Drake back.» Drake is an artist who has failed over the years to accustom his listeners to a possible stylistic change. He has not worked on the refinement of his character's storytelling, thus making the hard core of his fans tremendously nostalgic for the first version of himself he provided. That is not to say, however, that his more recent experimentation with fits far removed from the stereotypically masculine view of the rapper should be vilified by uneducated people. In short, in the face of Andrew Tate's deplorable phrases, there needs to be an extra effort from rappers who need to convince the public that rap is not just about a masculine narrative of firearms and slices of street life.