Leave "Blonde" alone Some reflections on the controversy triggered by Andrew Dominik's film on Marilyn Monroe

A lot has been said about Blonde, from Indie Wire, which called it a «pornography of pain», to Esquire, which defined it as «unfair and arrogant», to the scrutiny of the fetishization of female pain in The Cut, while on twitter there were even those who were disgusted by the film's inherent 'anti-abortion message'. In addition to fan outrage on social media, the film has also been panned by several film critics, including Manohla Dargis of The New York Times, who wrote in her review: «Given all the humiliation and horror Marilyn Monroe endured during her 36 years, it's a relief that she didn't have to suffer through the vulgarities of Blonde, the latest necrophiliac entertainment to exploit her.» Well, after two hours and forty-five minutes of the film directed by Andrew Dominik from Joyce Carol Oates' 775-page magnum opus, I felt no outrage whatsoever. But reading the reviews, I have often wondered when exactly we came to believe that morality is a prerequisite for a film, how we could expect a film adaptation set in 1950s Hollywood not to be profoundly patriarchal, and when we became such fine connoisseurs of Marilyn Monroe's life that we could think of making diktats about what should or should not be included in her biography, which is not even a biography.

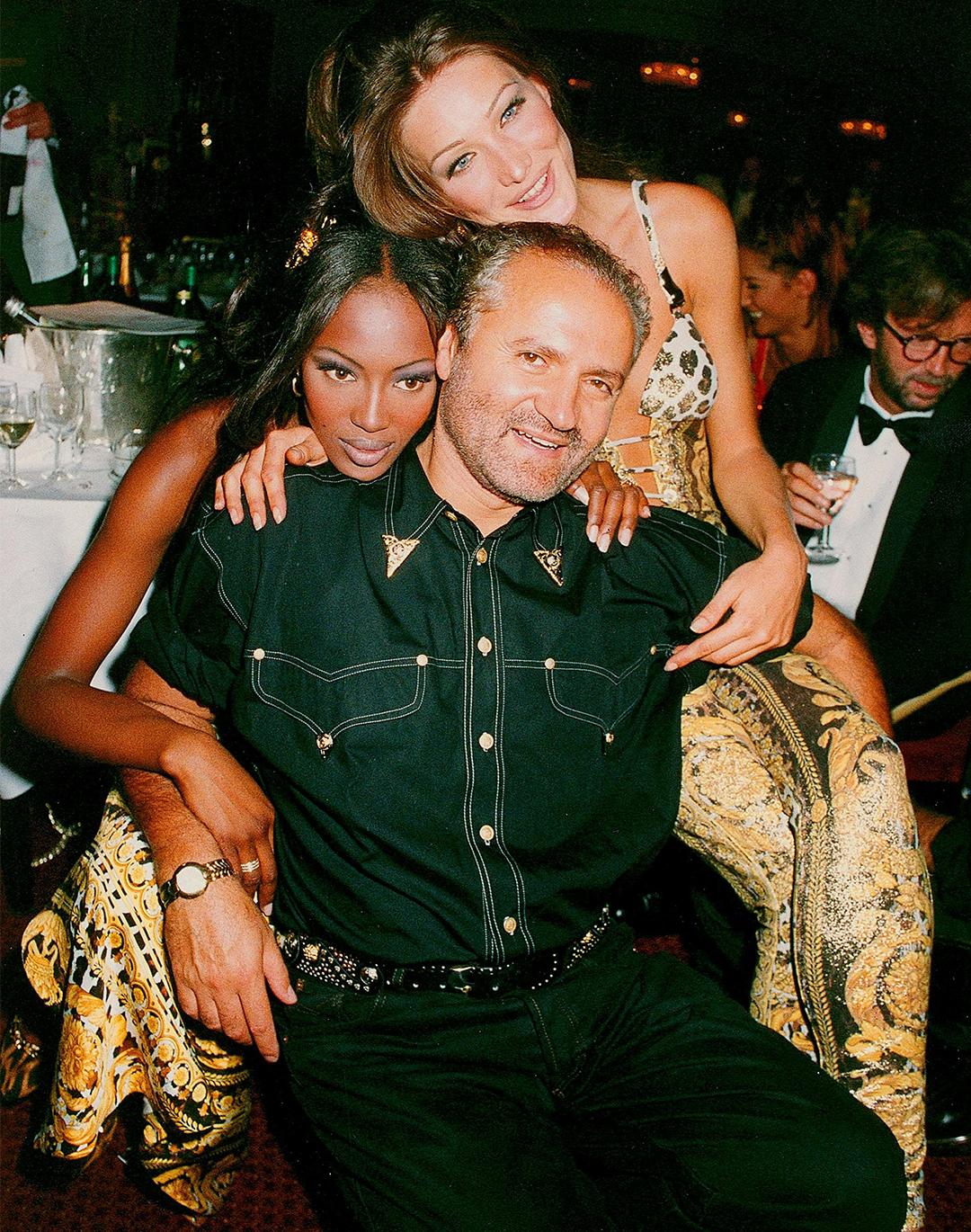

Basically, Blonde is the (admittedly fictional) story of a trauma that Norma Jean Baker really suffered at an early age, when an absent father and a schizophrenic and abusive mother laid the foundations of a life spent chasing male approval, but even more so trying, and failing, to build the family unit she never had. Out of this unbridgeable lack is born Marylin Monroe, almost a dissociated personality who comes to Norma's rescue if the pain is too intense to bear, as when, after what could be described as a psychotic crisis and a massive injection of sedative, she sees herself smiling in the mirror or repeats, during a forced abortion, to 'enter the circle of light', to act, so that everything will pass. A succession of abuses and men (whom Norma rigorously calls 'daddy'), in which the only consensual relationship portrayed is a manage a trois, in a psychedelic alternation of past and present, black, white and vivid colours - iconic the scene in which, during an acting lesson, Norma starts screaming like an obsessed and, when questioned about the reason for such a state of agitation by her teacher, replies 'I was just remembering' All the characters that present themselves to her seem like a lifeboat from self-destruction, all of them exploiting her for something: Darryl Zanuck of 20Century Fox for whom an audition amounts to rape; the two sons of old Hollywood - Charlie Chaplin Jr. and Edward G. Robinson Jr. - who taunt her with fictitious letters from her father that have never been found; her second husband, Joe DiMaggio, who considers her film career little more than prostitution; her third husband, Arthur Miller, played by Adrien Brody, who cares more about what being married to a sex symbol does to his intellectual status and exploits her as an inspiration for his work; JFK who only appears for the time of a fellatio and, of course, the audience, who like a uniform, voracious, animalistic mass, welcomes her as if she were a human sacrifice in the making.

just watched #Blonde ... it puts norma/marilyn in a box that only allows to her be abused, sexualized, or call people daddy. extremely strange. maybe we stop letting misogynistic men try to make groundbreaking films about women- of which they know nothing about.

Asked about her review of the film, Oates - who was not involved in its production - tweeted: «I think it was/is a brilliant piece of art cinema obviously not for everyone. Surprising that in a post #MeToo era the raw exposition of sexual predation in Hollywood was interpreted as 'exploitation'. For young starlet Norma Jeane Baker, there was no chance to 'tell'/'report' rape. No one would have believed her, no one would have cared; and she would have been abandoned by the studio and blacklisted. So, the film 'Blonde' exposes rape, 50 or 60 years later» Oates wrote. «The cruel exploitation of Marilyn Monroe by, among others, John F. Kennedy is well known to biographers of MM and Kennedy; but its transposition to the screen is difficult for some viewers to see.»

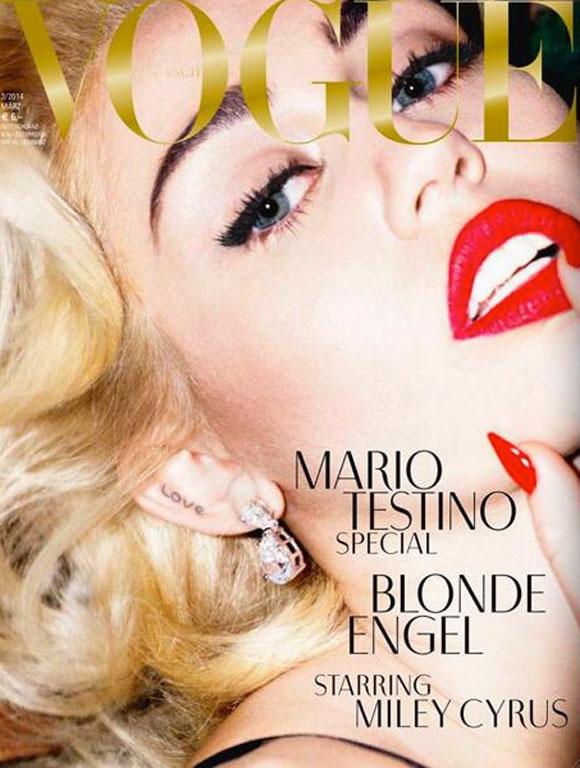

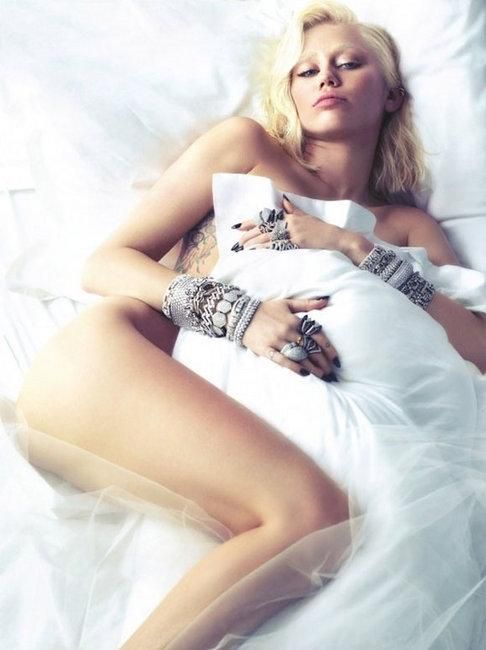

Andrew Dominik's intent was not to faithfully transpose Marylin's biography, nor to provide an uplifting portrait of her, arguably not even to elevate the background of Hollywood's most iconic diva to a universal parable about the exploitation perpetrated by men against women. The intent is to tell a disturbing story in a disturbing way. The result is aesthetically sublime in both Anna De Armas' flawless performance and cinematography, a film that in the midst of a rabble of dull, pulseless cinematic products, is able to stir something in the viewer, be it revulsion, outrage or simple reflection. The representation of pain, female or otherwise, is a recurring trope, a gateway to artistic expression and an integral part of everyone's human experience; fetishization is often a way of accepting suffering by aestheticizing it. To think that every form of art must be moral in itself and created by people who are themselves moral is misguided and profoundly dangerous for artistic production in a decade in which we try to reduce everything to a polarizing ideological manifesto to be tweeted on social media.