Pros and cons of paying in instalments Risks and dangers for those thinking of bypassing the system

Buy now, pay later in three installments—or perhaps don’t pay at all. In the era of deferred consumption, the very concept of credit access has transformed: are we truly wealthier, or just more indebted? Not long ago, paying in installments was a lengthy and bureaucratic process, tied to financial institutions and paperwork worthy of a Kafkaesque novel. Today, that has radically changed. Payment deferrals have become instant, requiring just a swipe—almost automatic—encouraging a consumption model reminiscent of the American approach to debt. In the United States, the economy is traditionally built on encouraging private debt, with consumer credit accounting for over 30% of the national GDP, according to the Federal Reserve. This model is now spreading in Europe as well, turning the concept of economic availability into a mere matter of credit access. More and more consumers are being driven to purchase goods and services far beyond their actual means. But adopting this mindset might be more dangerous than it seems.

Doordash and Klarna have signed a deal where customers can choose to pay for food deliveries in installments. pic.twitter.com/8tfYByPJwz

— Pop Crave (@PopCrave) March 21, 2025

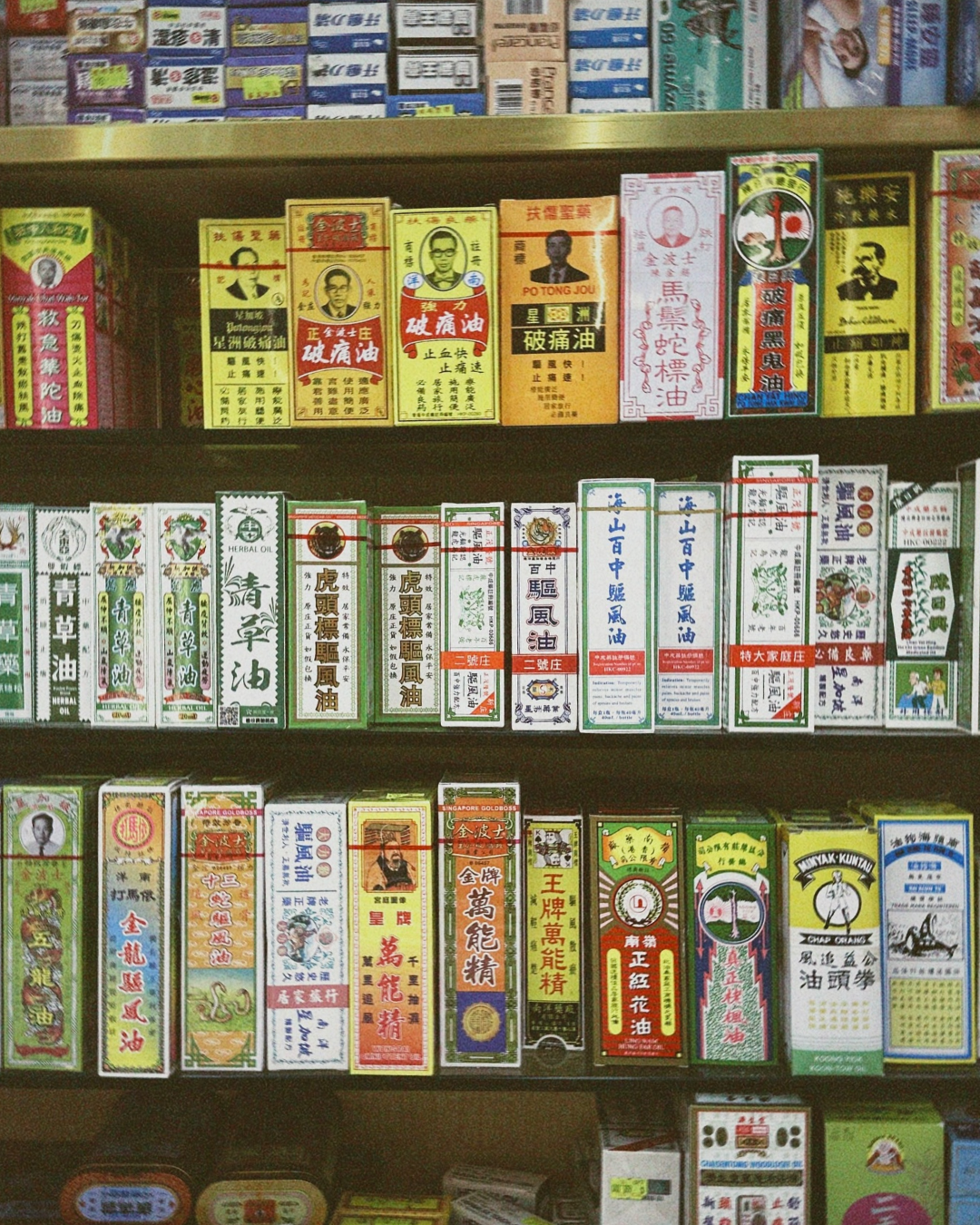

With the exponential growth of e-commerce and the digitalization of payment systems, the Buy Now, Pay Later (BNPL) model has emerged as the new frontier of consumption. Companies like Klarna, Scalapay, and PayPal have revolutionized how consumers interact with money: according to a report by Worldpay FIS, BNPL accounted for about 5% of global e-commerce transactions in 2023, with double-digit growth projected in the coming years. However, this ease of purchasing also brings risks. More and more users, especially young people, accumulate expenses that exceed their actual ability to repay. In countries like the United Kingdom, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) has already launched investigations into the sector, highlighting that 1 in 10 BNPL users is already struggling to pay off their debts.

While social media consumes every trend in the space of a scroll with the ease of a click, some trends prove more insidious than others. On TikTok, users joke about «not paying Klarna»: more and more people post screenshots of their outstanding balances in a defiant tone, turning debt into a trophy to gather hundreds of thousands of views. This narrative has led the Chinese video platform to intervene directly, introducing explicit warnings to discourage improper behavior. Now, searching for «What happens if I don’t pay Klarna» brings up a lengthy and explicit warning to inform and dissuade users from adopting unethical practices. A necessary move, considering Klarna processes about 2 million daily transactions and monitors its users' financial status in real-time.

Ryanair ora permette di pagare a rate, questa sarà la mia fine pic.twitter.com/eZNfylmgS6

— (@inomniapparatus) November 14, 2024

But is it really that easy to cheat the system? In reality, those who don’t pay may face severe consequences: failing to repay can result in a credit report entry in CRIF (Central Credit Register), risking classification as a "bad payer." This status can jeopardize the ability to obtain future financing, from buying a car to securing a mortgage. On the other hand, BNPL companies claim to operate with risk mitigation policies. Klarna, for instance, states that less than 1% of its users are delinquent and has implemented tools to monitor customers' financial behavior in real-time. «If a customer misses a payment, we limit their access to services to prevent them from accumulating debt», said Klarna’s Country Manager for Italy & Greece, Luigi Traldi. «Klarna evaluates each transaction based on hundreds of parameters, including our internal creditworthiness analyses and external data from a light credit check in collaboration with Experian. As a result, access to Klarna’s services is never guaranteed, not even for regular customers. For new users, we start with low credit limits, increasing them gradually only if they demonstrate responsible repayment behavior.»

In short, those who think they’ve found a loophole by paying the first installment and ignoring the rest may have underestimated the consequences. Facta lex, inventa fraus—the principle that for every law, there is a way to circumvent it—may not apply in this case. The financial repercussions are real and potentially damaging, from the inability to obtain future loans to serious credit issues. Perhaps it's time to reflect on a broader question: is BNPL an opportunity for the democratization of access to goods, or the prelude to a society where debt is the norm and creditworthiness a privilege?