What is happening with Gianni Agnelli's inheritance Private investigators, lawsuits and a disputed art collection

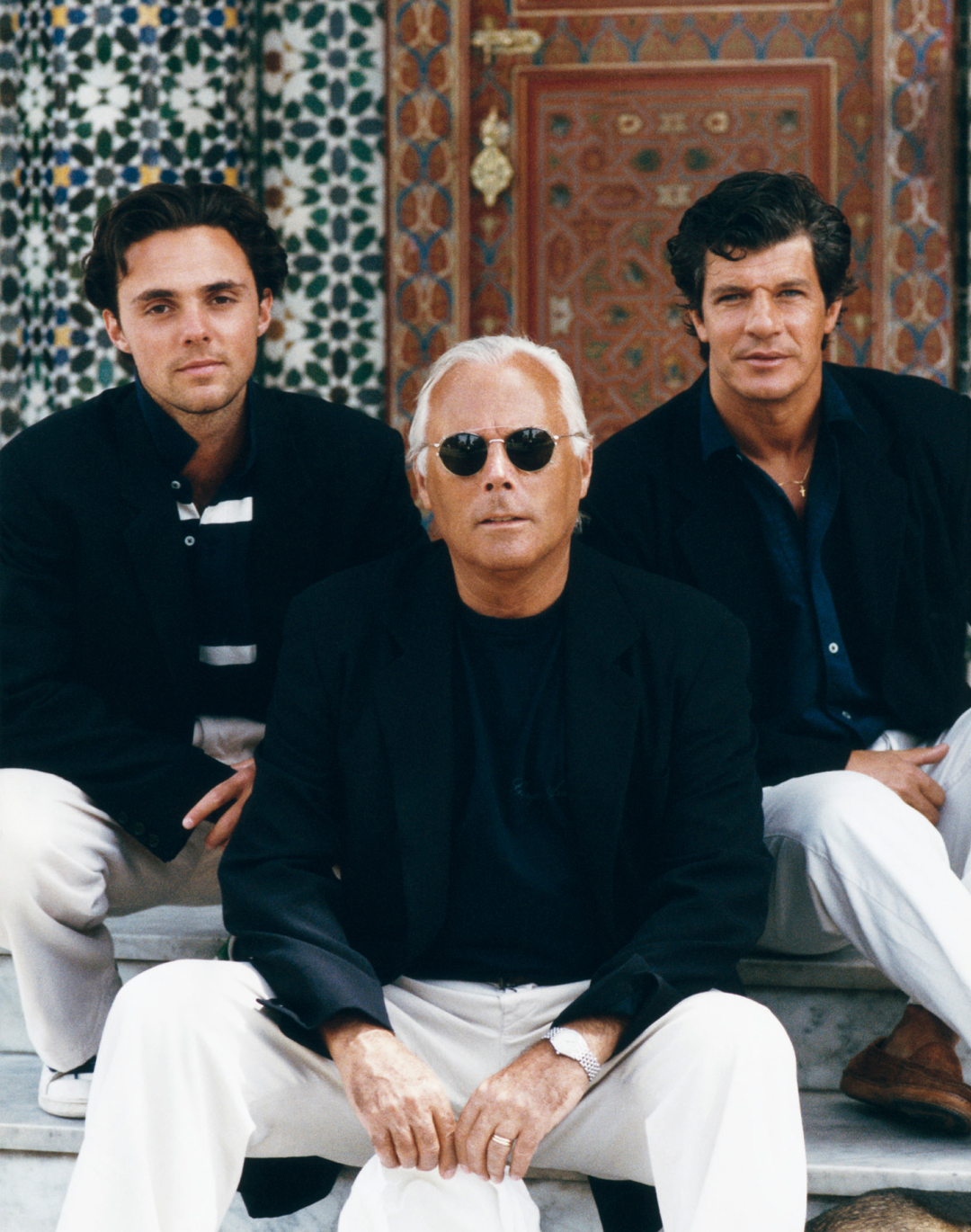

Last Thursday, the Italian Court of Cassation rejected the ruling that dismissed Margherita Agnelli's lawsuit against her own children, shedding new light on the tumultuous legal dispute involving the Agnelli family, one of Italy's most prestigious industrial dynasties. The case, deeply rooted in succession law, corporate control, and a multi-billion-dollar estate, is a complex web of events spanning several decades. The family dispute within the Agnelli family traces back to years of family history and the fervor of Gianni Agnelli's leadership. On one side is Margherita Agnelli, Gianni's daughter, and her children from the second marriage to Serge de Pahlen. On the other side are the three children from Margherita's first marriage to Alain Elkann: John, Lapo, and Ginevra. The main issue is control of Dicembre, the major shareholder in Giovanni Agnelli BV, which, in turn, controls significant companies like Exor, Stellantis, Ferrari, Cnh Industrial, and Juventus—a key company serving as the family's "safe." Some time ago, the Turin court decided to suspend Margherita Agnelli's lawsuit against the Elkann children, awaiting the outcome of similar Swiss legal proceedings. However, the Court of Cassation overturned this decision, requesting further clarification and ordering the resumption of the case within three months. This controversy, beyond financial matters, also revolves around the custody of an invaluable art collection.

The mystery of the missing paintings

The contested properties include real estate in Turin and Rome: Villa Frescot, Villar Perosa, and a large penthouse near the Quirinal in Rome. According to Agnelli's 1999 will, at his death, these properties were to be assigned with "lifetime usufruct to my wife Marella and naked ownership to my two children Margherita and Edoardo," the latter unfortunately passing away by suicide in 2000. However, in 2004, Margherita, Agnelli's daughter, signed a settlement agreement and a succession pact with her mother in Geneva, waiving her future inheritance in exchange for about 1.4 billion euros. Upon Marella's death in 2019, Margherita acquired the three properties, previously granted for use to her children. According to Margherita's lawyers, 636 highly valuable works were missing from the properties, including pieces by artists such as Canaletto, Tiepolo, Goya, as well as Francis Bacon and Monet. The Elkann brothers argue that the inventory of "objects in the Rome property," signed by Marella and Margherita, intentionally omitted page 75 where these paintings were listed. The reason given is that the works belonged to Marella, who had purchased them, and not to Gianni; therefore, they should have passed to the three grandchildren as stated in Gianni Agnelli's wife's will. However, Margherita contested this narrative, accusing the Elkann children of concealing artworks in 2019.

In her quest to locate the art collection, Margherita Agnelli hired private investigators. This summer, on August 31, the Milan Public Prosecutor's Office and Swiss magistrates had planned a targeted search at "box no. 253 of the extraterritorial cabins at the Magazzini Generali with Punto Franco Sa of Chiasso," as reported by Il Corriere. This space, rented by a Swiss art consulting and trading company, was indicated by Margherita Agnelli and her private investigators as the presumed location of the stolen works. However, in the specified customs cabin, neither the paintings nor any relevant traces were found through camera examinations, analysis of computer records, or badge access checks. Customs documentation showed that every movement of the works was conducted under strict customs supervision, making it difficult to attribute any illicit conduct to the suspects. In light of these circumstances, the Milan Public Prosecutor's Office requested the closure of the theft hypothesis. Not only were there no traces of the paintings, but the owner of the company renting the space and its carriers were not implicated in any illicit activity. However, Margherita Agnelli did not give up, opposing the archiving together with her lawyer Dario Trevisan at the GIP Office of the Milan Court.

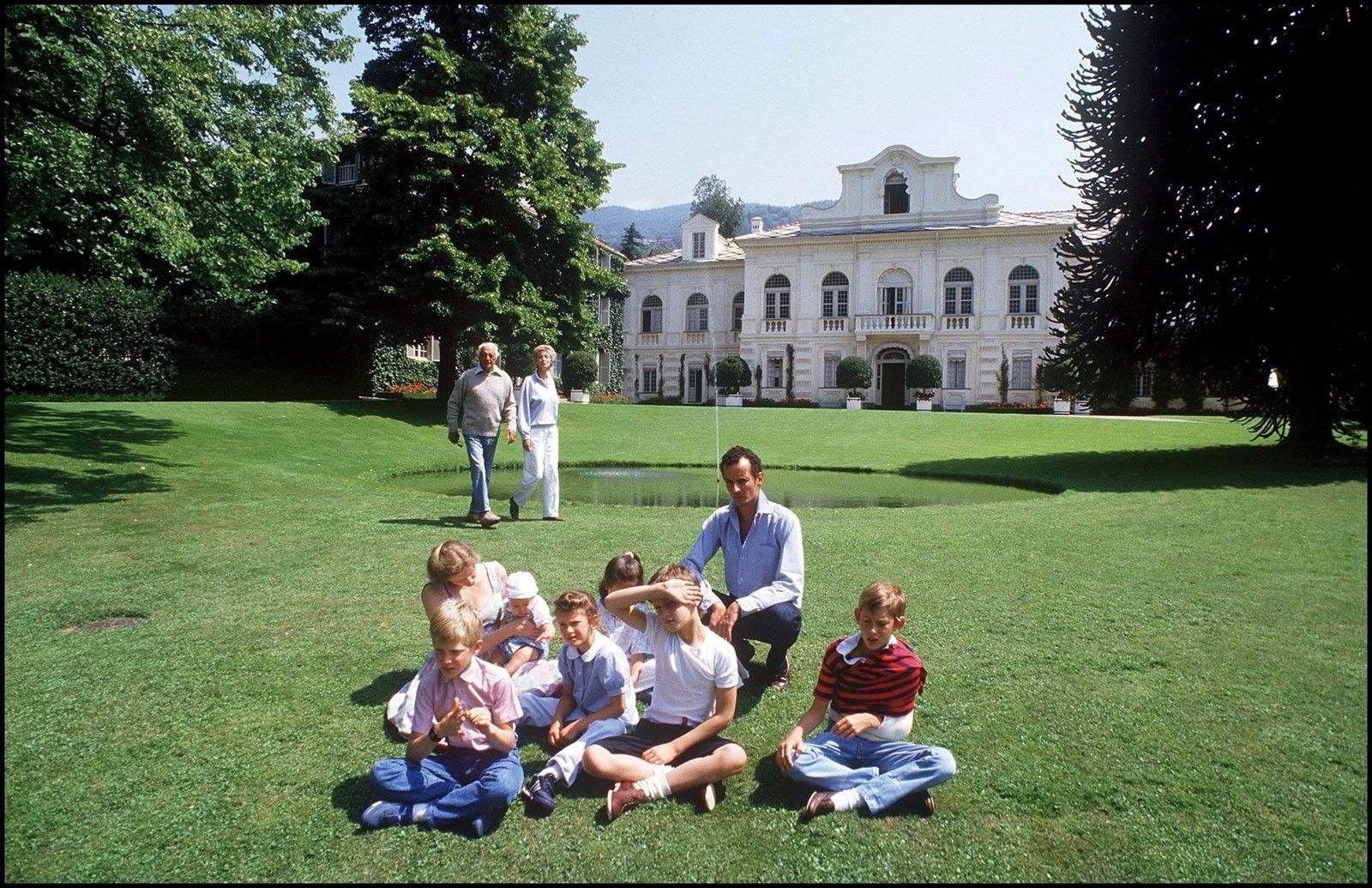

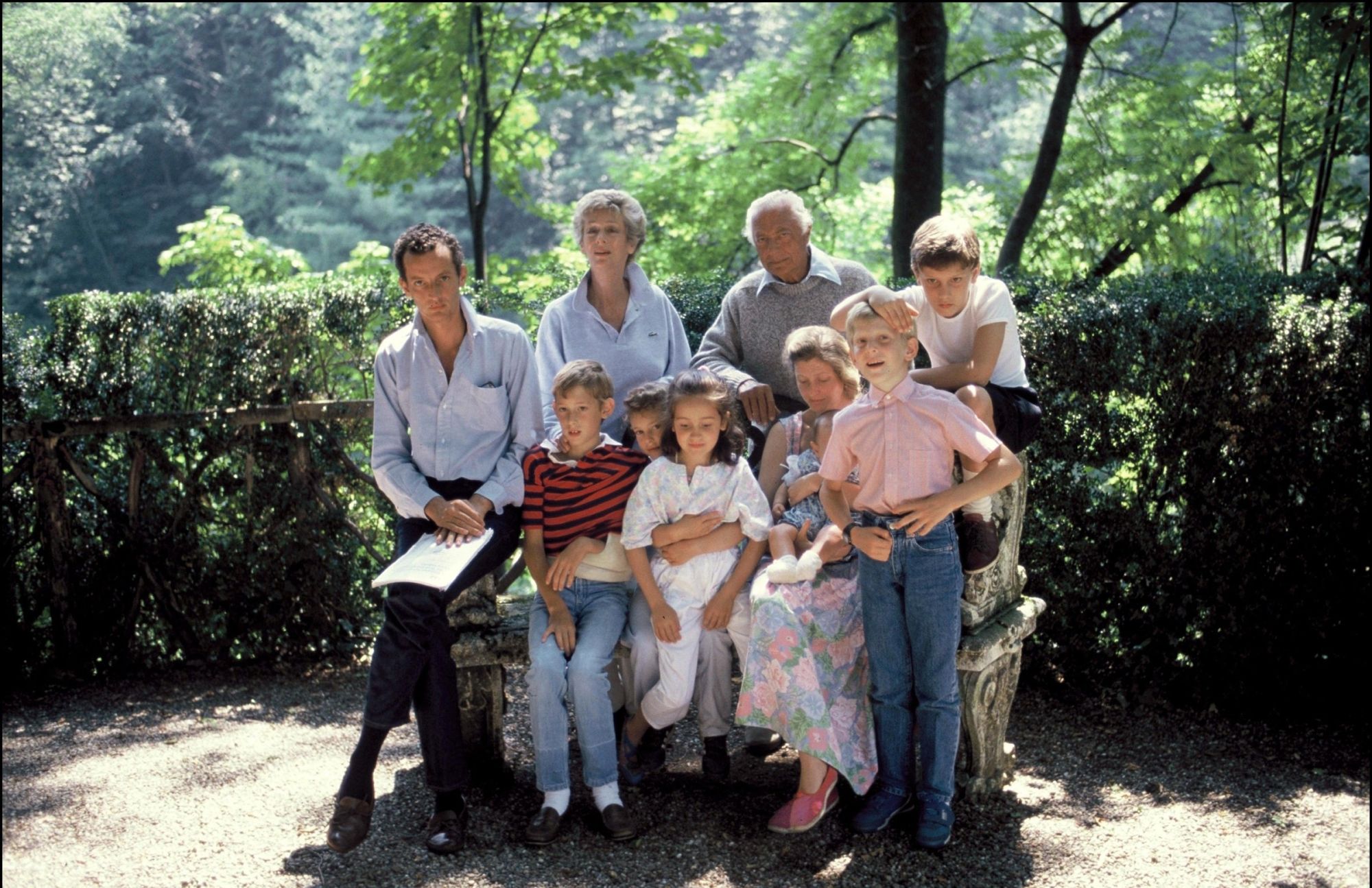

The Agnelli clan's heritage

To understand the reasons behind the legal dispute involving Margherita Agnelli and Gianni Agnelli's children, John, Lapo, and Ginevra Elkann, we must go back to the roots of the problem—a principle always advocated by Gianni Ag nelli himself: that in the family, there should be a single leader. After the tragic suicide of Edoardo Agnelli and the death of the other designated heir, Giovannino Agnelli, due to intestinal cancer in 1997, the mantle of the heir fell on John Elkann, Margherita Agnelli's eldest son, with the approval of the entire family. In 1997, John Elkann already owned 24.87% of Dicembre's shares, and with Gianni Agnelli's death in 2003, that stake increased to 33.3% and 58.7% with Margherita's exit from the shareholder group. When Margherita ostensibly withdrew from the game and took her cash-out, renouncing her mother's future inheritance and, consequently, rights to the Dicembre company. But in 2020, Margherita Agnelli initiated a new legal action, arguing that the 2004 agreement was void because renouncing a future succession is not provided for by Italian law. Margherita Agnelli's lawyers, led by attorney Dario Trevisan, argue that Turin is the competent jurisdiction, as the mother died in Italy and had her habitual residence in the country. The Elkann children, however, claim that the Turin judges should abstain under the 1933 Italo-Swiss convention, as a similar proceeding is ongoing in Switzerland, and the grandmother had residency in the country—a claim contested by Margherita. At the moment, Thursday's Cassation decision leaves things hanging. If Margherita Agnelli prevails, she will be allocated 50% of the assets, creating a profound imbalance in Dicembre—as a reminder, Margherita's faction also includes her children from the second marriage with Serge de Pahlen. The complexity of the issue is heightened by the ongoing disputes in Switzerland, where the validity of the 2004 agreements and the succession pact is being discussed. The decision of the Italian judges, based on which law to apply—Swiss or Italian—will be crucial. Margherita Agnelli has submitted a detailed memorandum to the Turin court, a result of the work of both Italian and Swiss private investigators who reconstructed the last 15 years of Marella Caracciolo's life. The mother reportedly spent most of her time in Italy, not in Switzerland as claimed by the Elkanns, making the case even more intricate.

Cassation's Decision

Last Thursday, the Cassation partially annulled the order issued by the Turin judges in the previous June, which had suspended the case pending the resolution of three ongoing legal proceedings in Switzerland. The Cassation highlighted that the Turin order did not fully explain the decision and violated Article 7, paragraph 3 of Law 218/1995, which allows the suspension of domestic judgments only if the foreign process is still pending. The Supreme Court emphasized that once the foreign process is concluded, the Italian process must resume. In this case, there were three pending processes in Switzerland, but that did not exempt the trial judge from carefully examining each process, considering that each, starting from the first to be concluded, would influence the ongoing process in Italy. The Cassation noted that the order not only failed to conduct an investigation in this regard but also ordered the suspension in a way that excluded any verification of the persistence of the suspension prerequisites, until the conclusion of the last process in Switzerland. This decision was deemed outside the scope allowed by Article 7, paragraph 3 of Law 218/1995. In summary, the Supreme Court ruled that the suspension of the process in Italy must be proportionate to the status of the foreign process and cannot extend beyond its conclusion. The resumption of the case will be scheduled within three months.