Why does the Pride merch look so shoddy? The colors of the rainbow, perhaps, are not enough

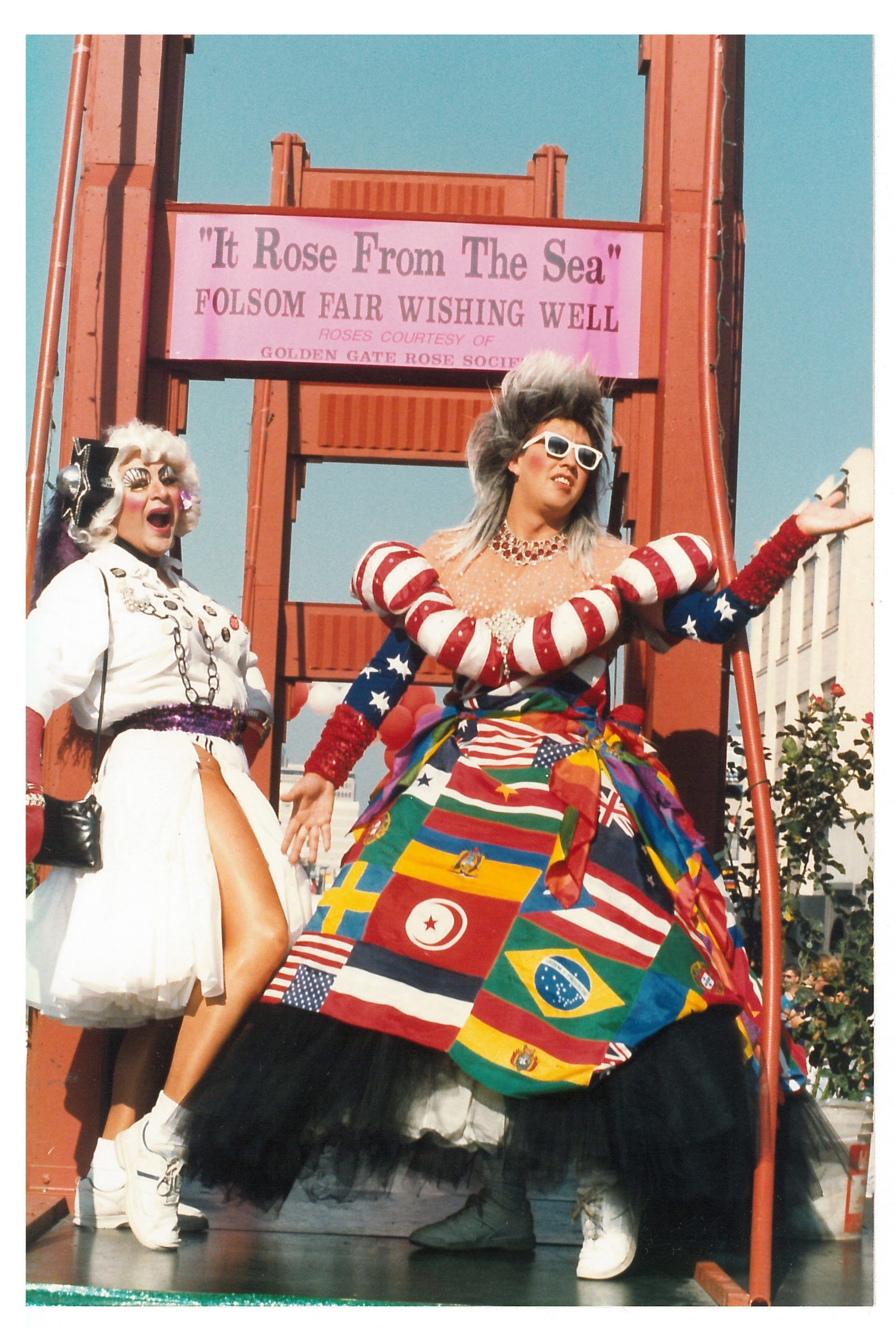

At the dawn of June, as Elon Musk's controversial tweet reminded us, our feeds are beginning to be tinged with rainbows. And along with them, so do store windows, t-shirt prints, corporate logos, and cosmetic and fast food packaging. On June 27 and 28, 1969, following a New York City police raid on the Stonewall Inn, a notorious gay nightclub in Manhattan, the homosexual community was the protagonist of a growing movement of riots, which resulted, the following year, along the streets of Chicago with the first Pride in history. Stonewall Riots are celebrated throughout June with LGBTQIA+ pride marches and parades, claiming less discriminatory legislation and promoting principles of social acceptance. Inclusive and egalitarian values that have come together under one symbol since 1978, when Gilbert Baker The Gay Betsy Ross (gay activist and former Army veteran) and Harvey Milk (the first openly homosexual U.S. politician) painted and sewed a rainbow flag for the San Francisco Gay Freedom Pride Parade.

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) May 31, 2022

Sex, life, healing, sunlight, nature, magic, peace, and spirit: the colors of the rainbow encapsulate in their pigments a message of universal love, which came to life through the beautiful handmade drag dresses made by Baker and a team of thirty activists. But what remains today of these garments of the highest craftsmanship is a multitude of products of dubious taste and quality, grouped under the highest common denominator of rainbow washing. From well-known furniture companies displaying "bisexual" sofas in limited editions, to fast fashion giants with basic collections declined in rainbow colors, to sandwich and snack packaging with accommodating messages printed on the labels: merchandise dedicated to Pride is becoming less and less credible, circumventing the concept of "gay friendly" with superficial and hasty marketing strategies. And along with superficiality also comes a kind of cultural appropriation, as in the emblematic case of Act Up, the first militant group in support of HIV patients, whose protest slogans have been swallowed up and repurposed by ready-to-wear fashion giants in the form of prints and pop decorations on T-shirts and sweatshirts.

After pinkwashing and blackwashing, now it's the turn of rainbow washing, which in addition to being a futile corporate tactic devoid of pragmatic implications, would seem to run counter to the concepts of variety-identitary but also aesthetic-of the LGBTQIA+ community. The creative industries' mad rush to June reveals a lack of care for collections dedicated to Pride, and it spills over into a series of maximalist and glittery products that leave less and less room for creativity and innovation. It is as if, for the past few years, the common imaginary of queer aesthetics has been shaped around a bunch of mass-produced items, whose message becomes increasingly weak and banal while the visual impact becomes increasingly violent. A double-edged sword that only reinvigorates prejudices against sexual minorities, as well as triggering a series of hashtags and explanatory memes about how a queer person really dresses-or would like to dress: not so much with the brazenness of Borat in a technicolor mankini, but rather with the nonchalance of Harry Styles in a lace blouse. What emerges from the impact of these products is that, in fact, the average target audience for a T-shirt whose print reads phrases such as "Love is Love" or "I Am Gay And I Slay," is not the gay community itself, i.e., the "pink money," but all those heterosexuals who somehow wish to show solidarity with the cause. For this reason, coupled with the fact that many corporations have no interest and/or time to delve into the history of queer culture, Pride merch has done nothing but arouse the outrage of the LGBTQIA+ community in recent years, benefiting from the "superficial" interest of a cis-heterosexual public.

Yet gay iconography is peppered with interesting and meaningful historical symbols that go far beyond the classic rainbow flag. Just think of the green carnation, i.e., "the flower of love," which gave its title to Robert Hitchens' scandalous novel about the relationship between Oscar Wilde and Lord Alfred Douglas, or the Hanky Code in which a bandana is used to make one's sexual preference known. Also, violets given to the woman for whom one feels Sapphic desire, the leather subculture, and the bisexual double moon. The research work should be much more thorough for anyone who wants to authentically address the LGBTQIA+ community during Pride month: at a time that is as celebratory as it is expected, protesters should feel free to brazenly display pride in who they are, but also in what they wear. But the desire to sell pushes more and more brands to adopt reductive, mainstream slogans, which in most cases have a repulsive effect on the communities represented, but provide very high visibility for the company and the wearer. And at midnight on June 30, as if by magic, it's all over to make way for the summer sales.