Rise and shine of Fake Tanning Has Y2K gone too far?

Trends come and go, but our dedication to a summer tan is something perennial. No matter how many times magazines try to convince us that paleness is more interesting, sophisticated or at least healthy, tanning remains one of the guilty pleasures of summer. Hence the secret of fake tanning's success, not only as a practice of artificial tanning, but also as a real aesthetic that evokes bleached blonde hair in the clubs of the 2000s, the healthy girls of Los Angeles or even the tanning bed mishaps of David Schwimmer in Friends and Anne Hathaway in Bride Wars. St Tropez, one of the leading self-tanning products in the UK, sells three bottles of tanning mousse per minute worldwide. Yet there seems to be a serious risk that the products that allow us to sport fake sun-kissed skin all year round will disappear from the market: «manufacturers are experiencing a shortage of the chemical solvent ethoxydiglycol, which is used to improve the consistency of skincare products and help them spread evenly over the skin, especially in self-tanning products» - reports The Guardian. A disruption in the global supply chain that has affected pharmacists and manufacturers, as in the case of Stockport-based Sunjunkie, and that mainly influences the UK, where the Chav aesthetic, similar to the Geordie Shore one, is still a living reality and around 41% of women use self-tanning products.

«If I had to choose a religion, the Sun as the universal giver of life would be my God Napoleon Bonaparte once said», but not all his contemporaries felt the same way. Until the 1930s, tanning was considered terribly démodé, tanned skin was for farm workers, while ladies of the aristocracy sheltered under parasols and hats during afternoon promenades. Tanning only entered the mainstream in the 1930s, when «Coco Chanel made tanning the height of fashion in the 1920s, as a key component of Riviera chic - says Justine Picardie, author of a biography of the French designer - in this way, she turned fashion on its head, so that tanned skin became the emblem of glamour rather than the peasant, of a wealthy life rather than outdoor work.» The arrival of the first bikinis in the 1950s and the first (almost) full-body tan did the rest, and it was in those same years that the first fake tanning product hit the market. It was called Man-Tan and it contained dihydroxyacetone (DHA), a chemical that some say was discovered by accident in the 1920s, when a nurse accidentally poured it on one of her patients' chests while hooking up an IV, only to discover the next day that the substance had coloured his skin. Little more than a brown dye, nothing like the sophisticated formulas we are used to today, so much so that it was only with the boom in tanning salons and cabins in the 1980s that tanning became popular with those who could not afford to winter in the Caribbean but wanted to pretend they had.

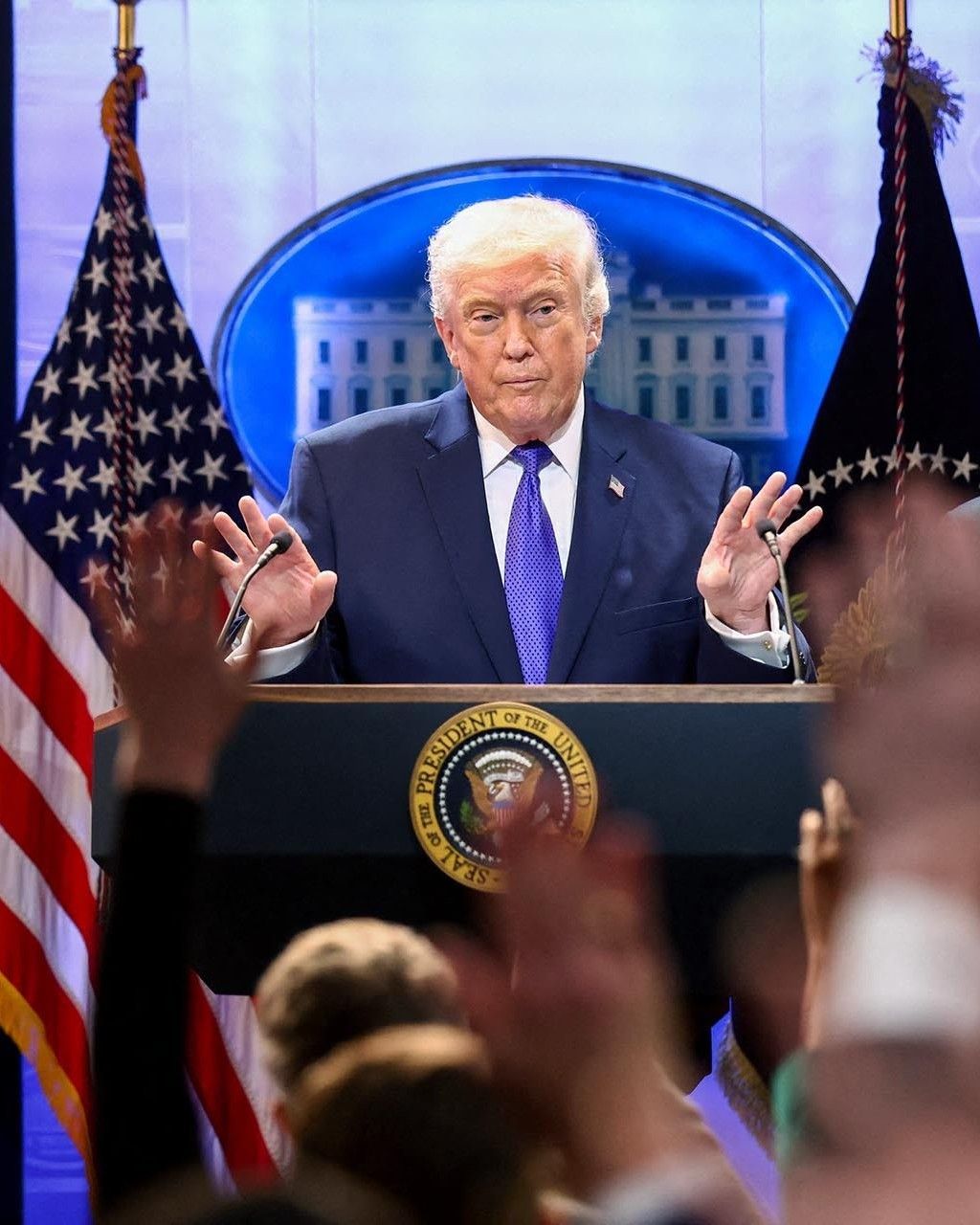

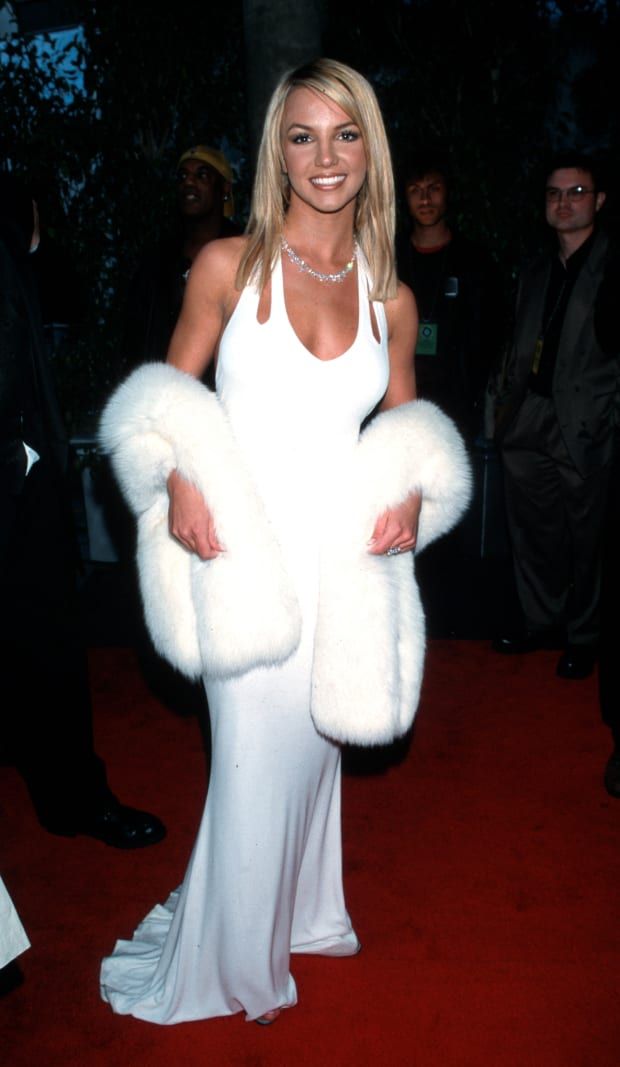

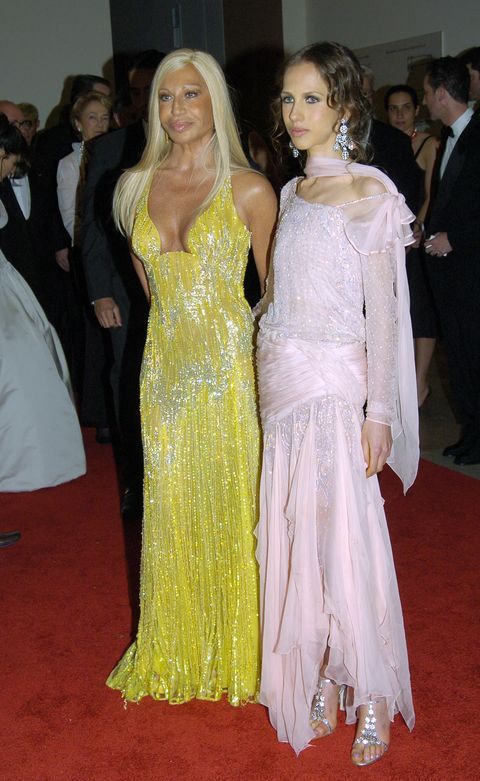

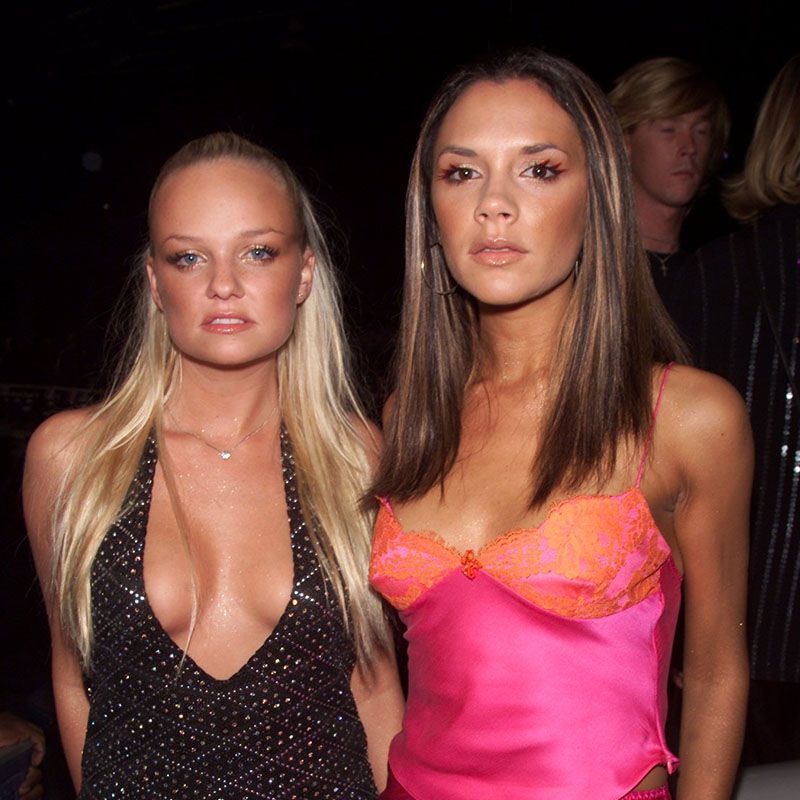

Although tanning beds were a must in the 1980s, it wasn't until the 2000s that the trend became, as an article in The Guardian in 2010 put it, 'the new normal'. These were the years of the skin show, of showgirls, Britney Spears, Shakira, Paris Hilton, Kim Kardashian and Nicole Richie, but above all they were the years of the Spice Girls and Victoria Beckham, who in 2001 had reached the same degree of saturation as a ripe orange, so much so that the Evening Standard called her "the original Tango'd woman", a brand of suntan oils famous in those years. Between Juicy Couture velvet jumpsuits, crotch-hugging jeans and rhinestones on your teeth, if there really is a revival that challenges common sense, it's the orange tan. In fact, in a Superdrug poll, overdoing it with fake tan was voted 'the biggest beauty mistake of the 20th century', and the organisers of Royal Ascot, the most important event in the social calendar where you can see many of the Queen's horses competing, have published a guide to discourage spectators from orange self-tanners. Back in the '0s we still had the excuse of unawareness, it was a new trend that we hadn't yet had time to digest and critically analyse, caught up as always in chasing celebrities in their latest (questionable) style choices. But now that Y2K is back in fashion, despite the years that have gone by and the notion that fake tanning is in some ways the epitome of bad taste, nothing can keep us away from tanning salons anymore, not even Elizabeth I's bans, if not a leak in the supply system of self-tanning companies. Could it all be a conspiracy?