How Sanremo became a showcase of alternative masculinity in Italy A process of redefinition that began with Renato Zero

If we think of Sanremo it is quite common that the first thing that comes to mind is a host of agè singers wearing a very formal white tie suit on the stage of the Ariston theater. But the history of the festival is also made up of exceptions, fluid, modern performers, histrionic outfits and impactful personalities that have challenged the public to question the male ideal, disregarding the patriarchal and macho dictates with which past generations have grown up. Maneskin, Achille Lauro, in some ways Morgan and before that Renato Zero, who for artistic needs, who for marketing, who to follow that trail of American singers who have made the history of world music: all have said no to the white tie suit, literal divided of man in society, with all its connotations of decorum and social roles and therefore direct symbol of heteronormativity.

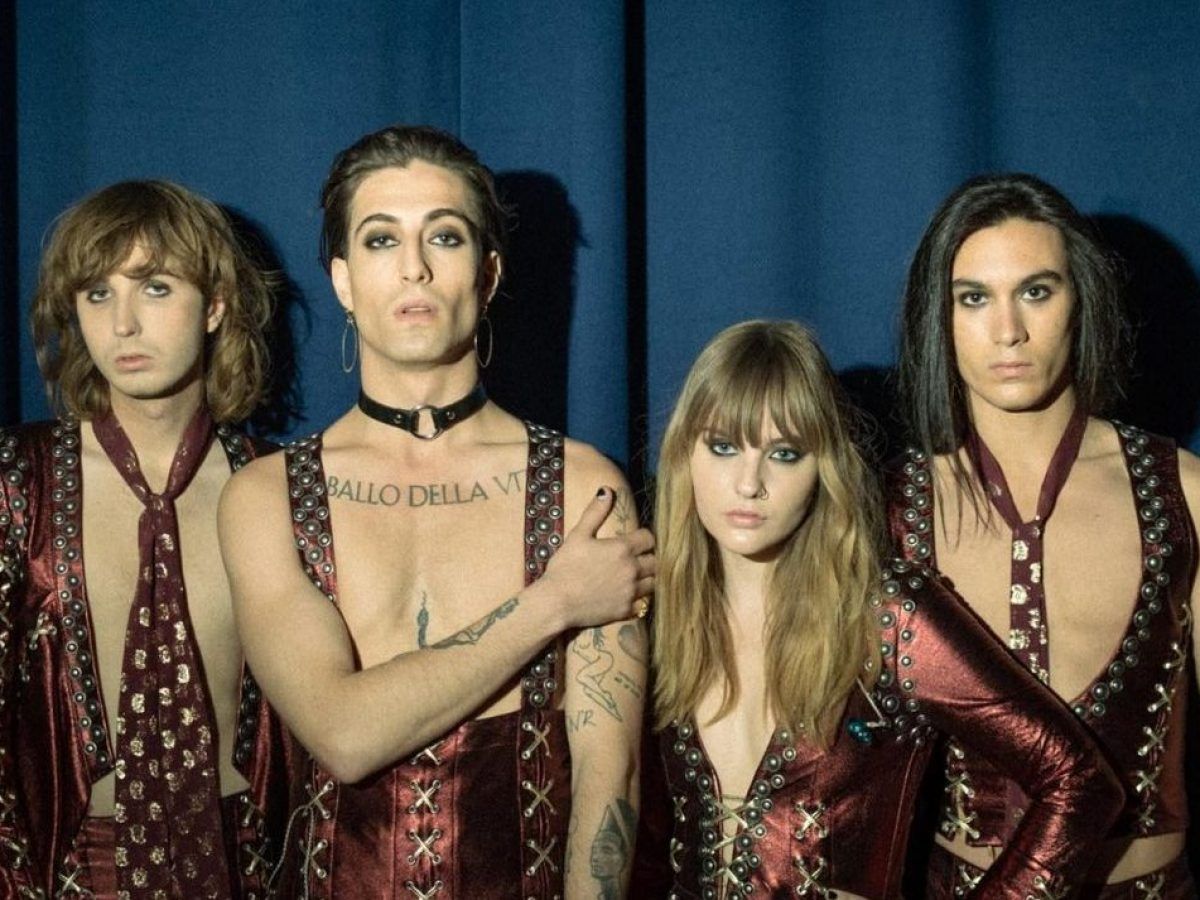

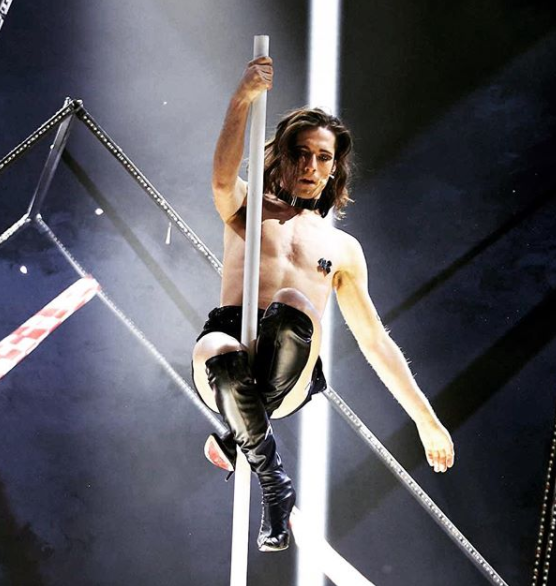

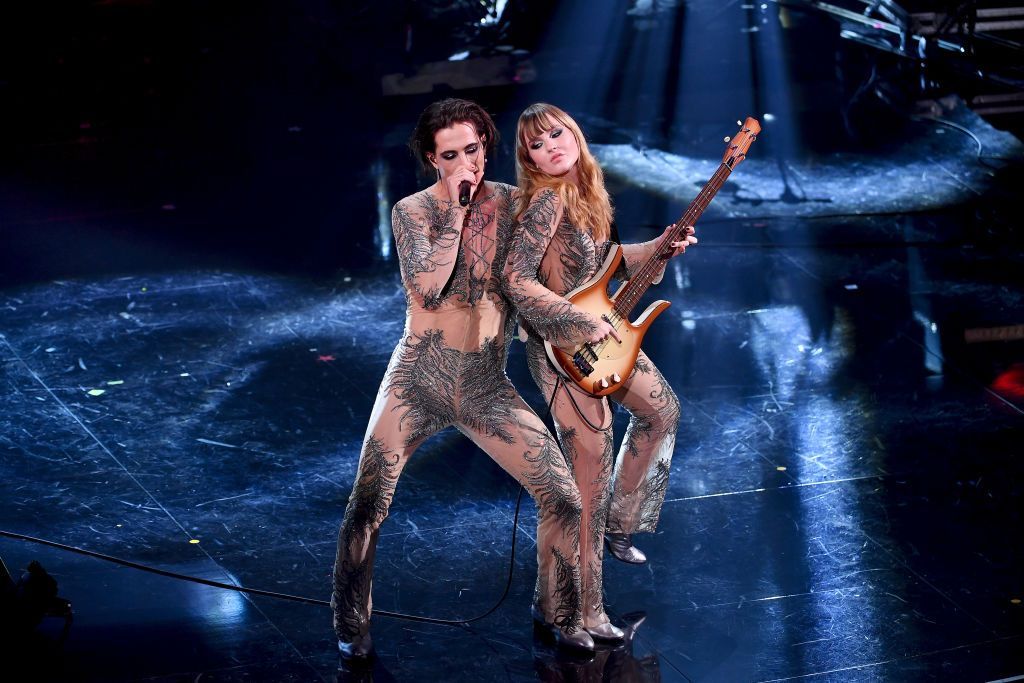

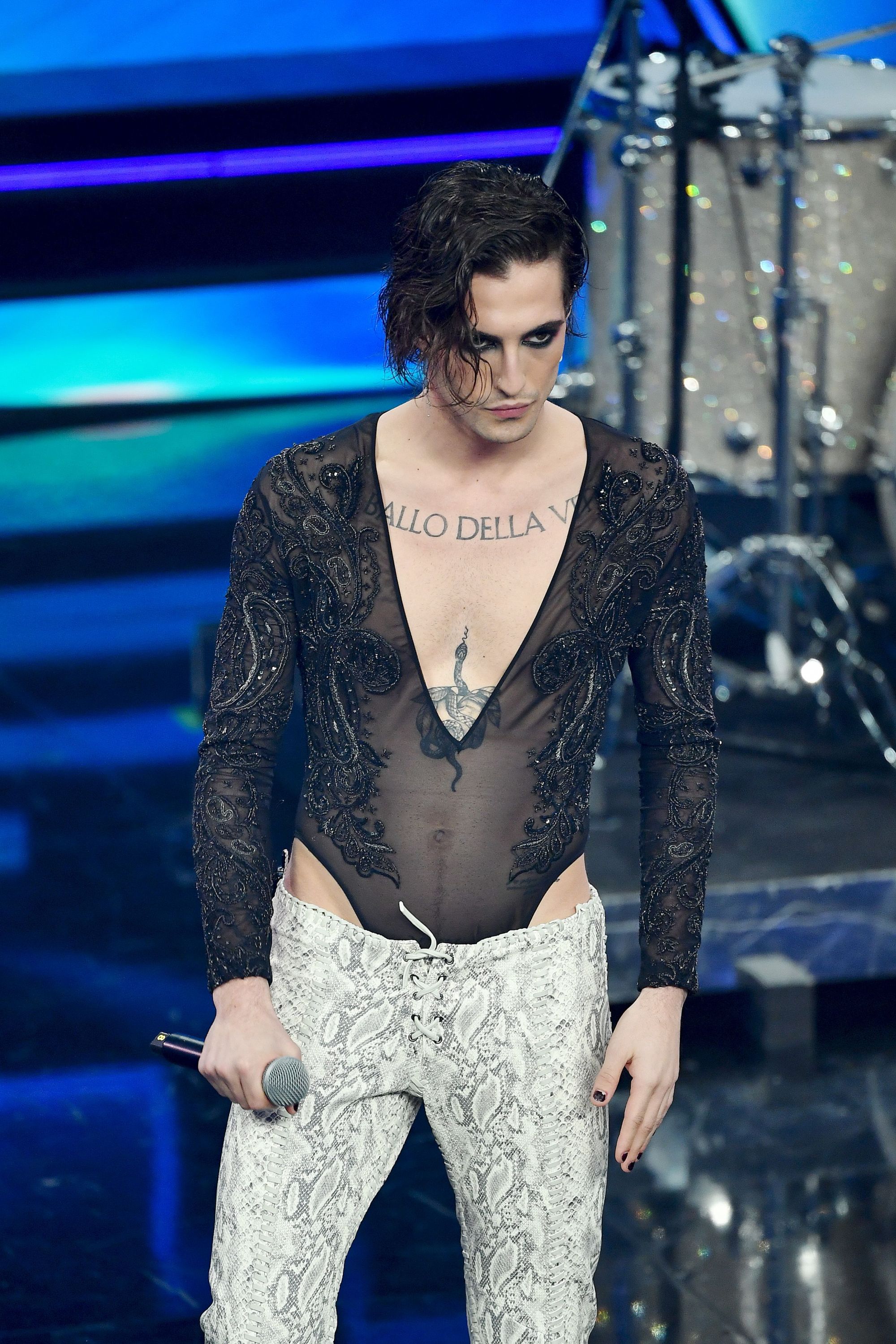

A milestone was reached when the festival was won by Måneskin, the first Italian band in the last twenty years to be propelled to international success in a very short time, winning X-Factor, Sanremo, Eurovision, and earning a spot on the Coachella stage. The Roman band, through collaborations with Etro and Gucci, had normalized a glam, openly sensual aesthetic, where masculine and feminine elements harmoniously blend without the need for distinction, monopolizing headlines with titles like "Even moms go crazy for Damiano." Sexual liberation represents the thematic core of Måneskin's stage persona, paradoxically, though, it was not they who were targeted by controversies but the guest Achille Lauro. The singer's outfits seen during the last two editions of the festival (unfortunately missing last year) stood out for their complex scenography, theatrical costumes born from the collaboration between Gucci and stylist Nick Cerioni, special effects, irreverent and provocative messages, and kisses with colleague Boss Doms. And let's not even talk about last year's episode between Fedez and Rosa Chemical. That the image of a young man engaging in homoerotic displays on the Ariston stage could make some of the audience frown in a country where the rejection of the DDL Zan was applauded was quite expected. Yet, the fiercest and unexpected criticisms came from the LGBTQ+ community, accusing the singer of queerbaiting.

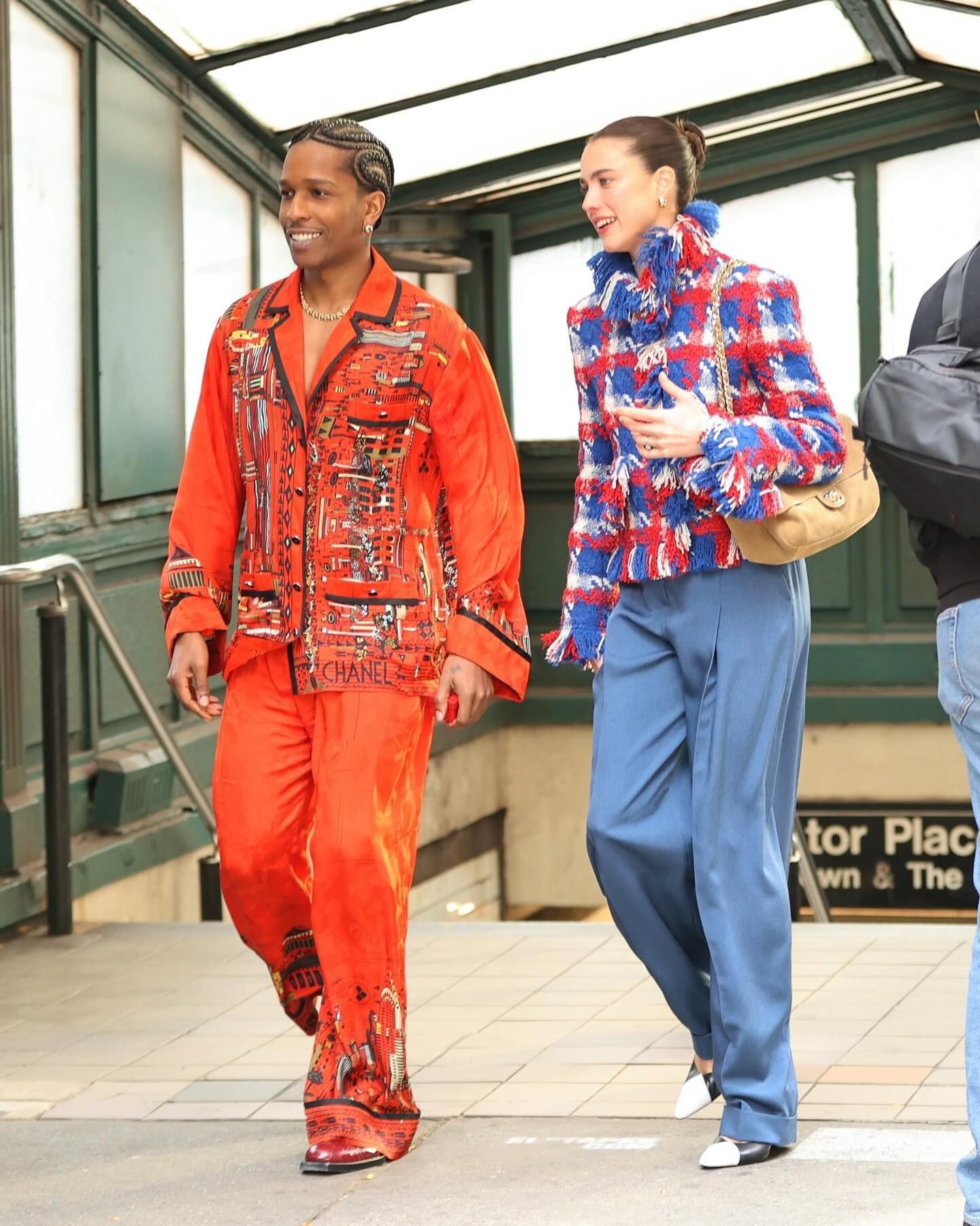

The accusation that the LGBTQ+ community has addressed to Lauro has been that of queerbaiting in the sense that the values he expressed, such as the fight against toxic masculinity, the praise of sexual freedom and full self-expression, would be a mere marketing gimmick because he who makes it spokesman is an openly heterosexual white man. The hypothesis that the artist has built an ad hoc character over time seems even more plausible if we think of his stylistic evolution, from the trapper aesthetic of the beginning, made of braids, teeth grills and loud jewelry, to an androgynous look and a chameleonic transformationism more reminiscent of a David Bowie or a Freddie Mercury. The artistic partnership with Alessandro Michele, the undisputed spokesman of the genderfluid aesthetic that included Lauro in Gucci's Pre-Fall 2020 lookbook as a character who was at the confluence of pop culture, music and aesthetic experimentation, has certainly contributed to this evolution.

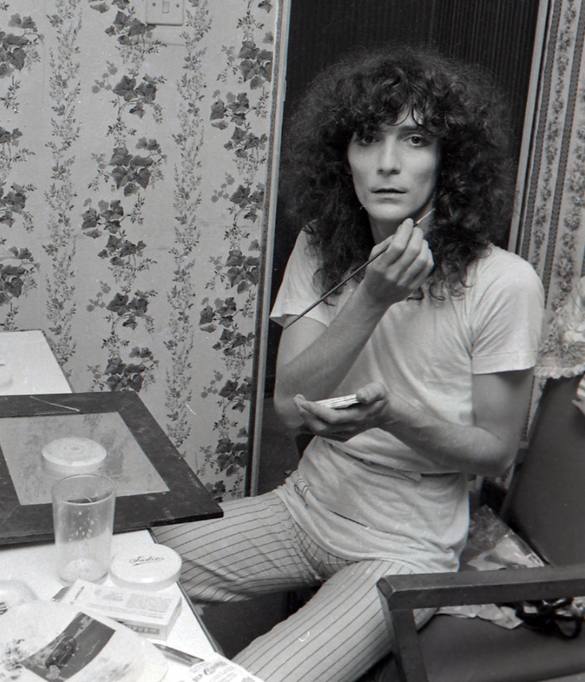

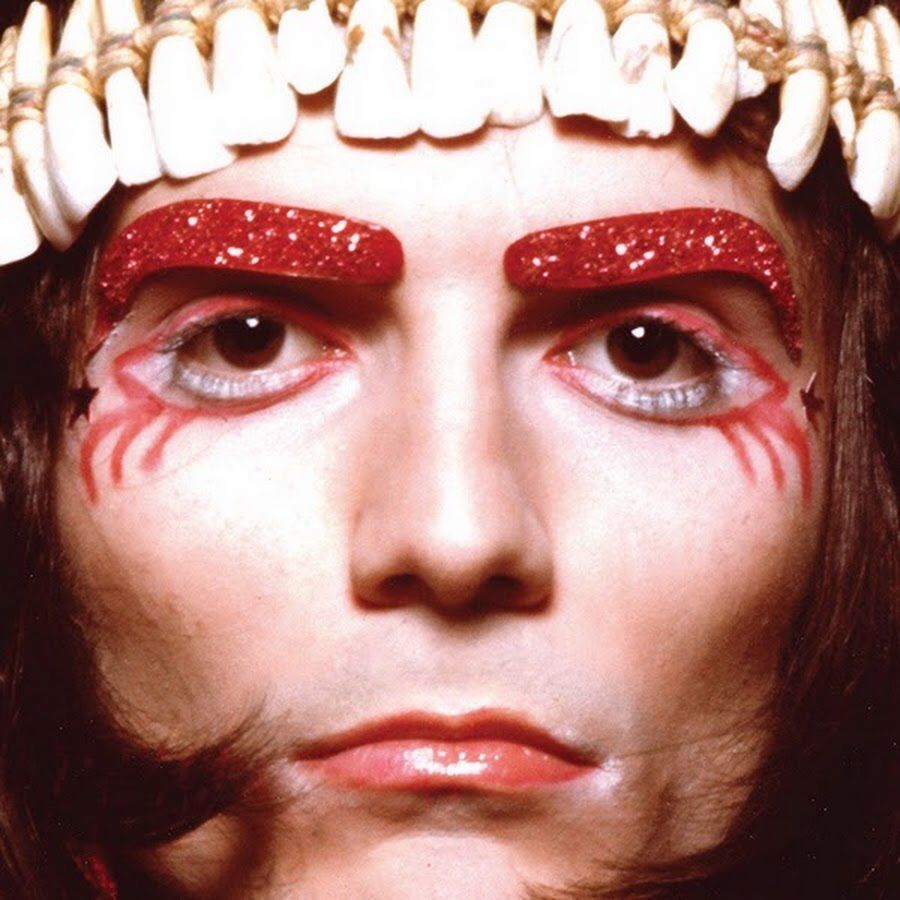

But the only true forerunner of gender fluidity in Sanremo is Renato Zero, the man who preferred music to military service and who, to escape it, presented himself at the medical examination wearing a pair of very thin red briefs. Whether you consider him a revolutionary transformist icon or an incognito conservative, Renato Zero and his cultural heritage have remained a point of reference with which all subsequent generations of singers had to confront. His fans will always be grateful to him for bringing home a glam dream that only England with David Bowie or America with Lou Reed seemed to be able to afford. From rock to the evil queen of fairy tales, from the Pellerossa to the Mad Hatter, from the tribute to the circus to the geisha, the Pierrot version with those red apples on the cheeks, angel version, devil, from the total white look to the total black of recent years. A contradictory character, in some ways irreverent that with Sanremo and the institutionality that it represents has always had frictions precisely because of his way of being and dressing. A break that started in '91, when he finished second on the podium after Cocciante despite the opinion of the public and then culminated with the rejection of the career award in 2009.

This year we will see again the Maneskin and Achille Lauro, but among the participants there are those who embody an even different type of masculinity: San Giovanni, the young talent who from the stage of Amici has climbed the Spotify charts, is certainly one of the most representative exponents of the soft boy aestethic, a new way of narrating virility that embraces and promotes the freedom to express fragility and introverted and sensitive attitudes. This type of style, made of pastel colors, semi-formal outfits, diamond sweaters, loose pants and intellectual poses legacy of hipster culture is going very strong in recent years: on TikTok the hashtag #softboyaesthetic has 1 billion views. In the era of the deconstruction of the binomials, between masculine and feminine, strength and weakness, the male subject who must constantly worry about the image he gives of himself, his social and public role, which must show himself perpetually dominant and winning, finds an alternative in these modern figures that allow a greater degree of self-expression and authenticity. A new way of perceiving masculinity in Italy that has forever changed every pre-existing mindset perhaps also thanks to the pioneering of Renato Zero and Sanremo.