When Martin Margiela was the creative director of Hermès And the unexpected chemistry between two worlds at the antipodes

It was in April 1997 that the Belgian designer Martin Margiela was appointed the new creative director of Hermès. Many wondered at the time how an avant-garde, pioneering creative, a fashion iconoclast, could have 'landed' at Hermès, and especially what had prompted Jean-Louis Dumas to make such an unlikely artistic connection. It was the 90s, Martin Margiela lived in anonymity: he refused to be photographed, he communicated with the press only by fax and at the end of the fashion show he kept the crowd waiting because, after all, his work was already quite eloquent. From tops made of plastic bags to waistcoats made of broken plates and wire, from human-sized doll wardrobes to dresses made of candles, Margiela's creations went beyond any avant-garde of the time, often even beyond the limits of the material. Between absolute anonymity and a production far removed from the minimal elegance of the Hermès family, the appointment of such a subversive figure at the head of a fashion house synonymous with traditional luxury made the press curious: how would Margiela interpret the Hermès classics? Was a compromise between the two really possible? But above all: what had prompted the conservators at the top of Hèrmes to make a decision that seemed (or perhaps was) a head-scratcher? The credit goes to Sanrdine Dumas.

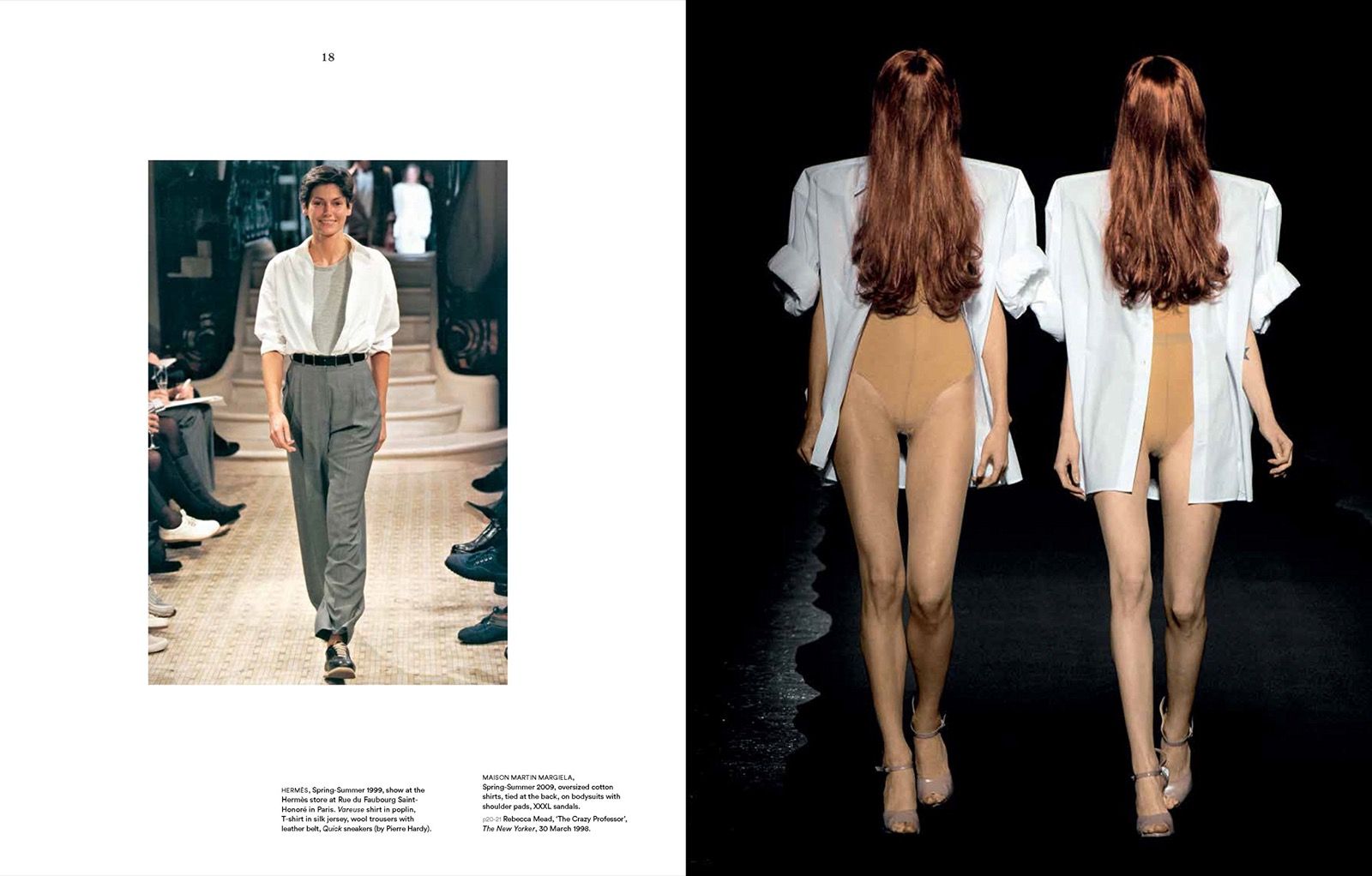

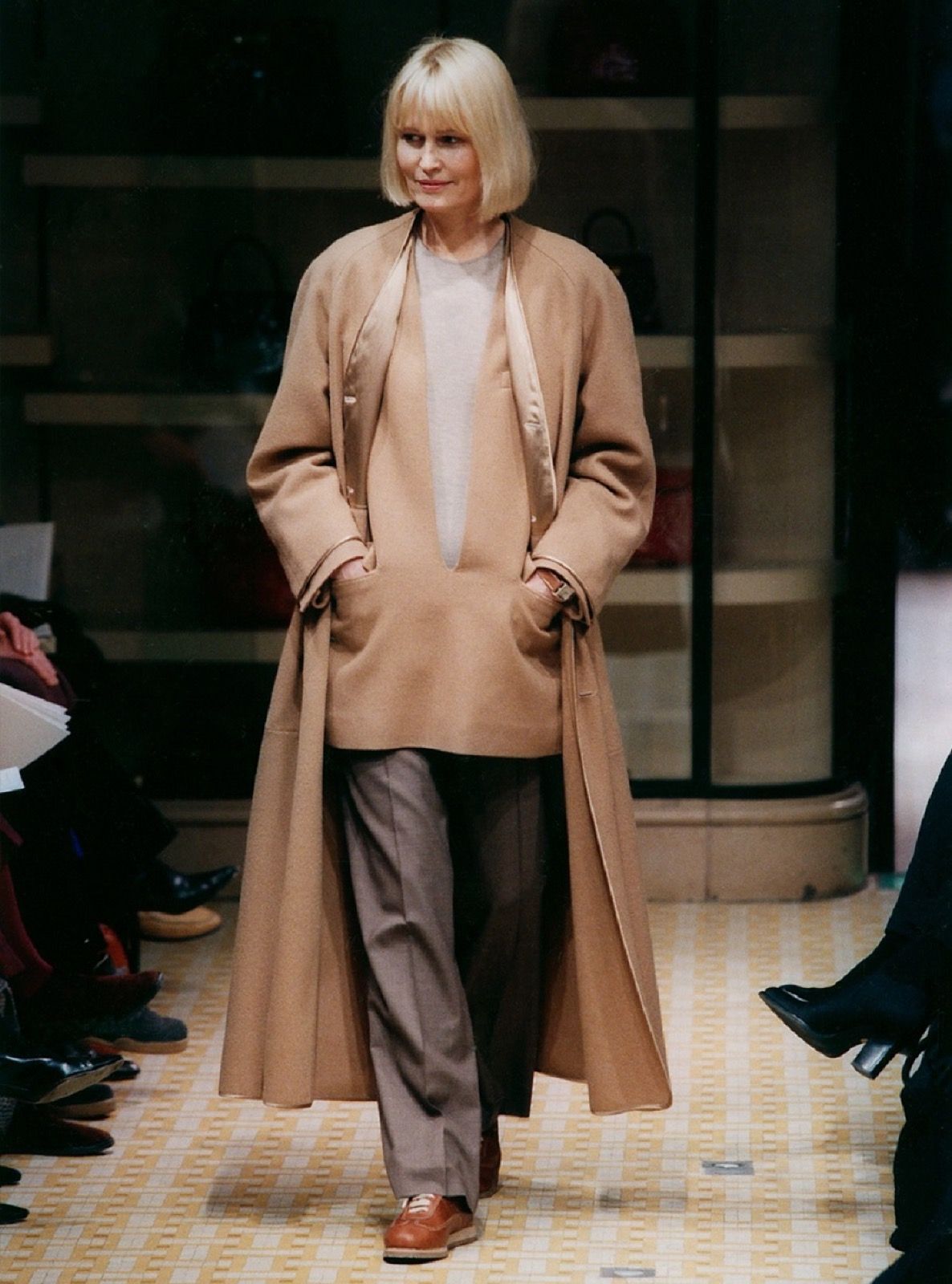

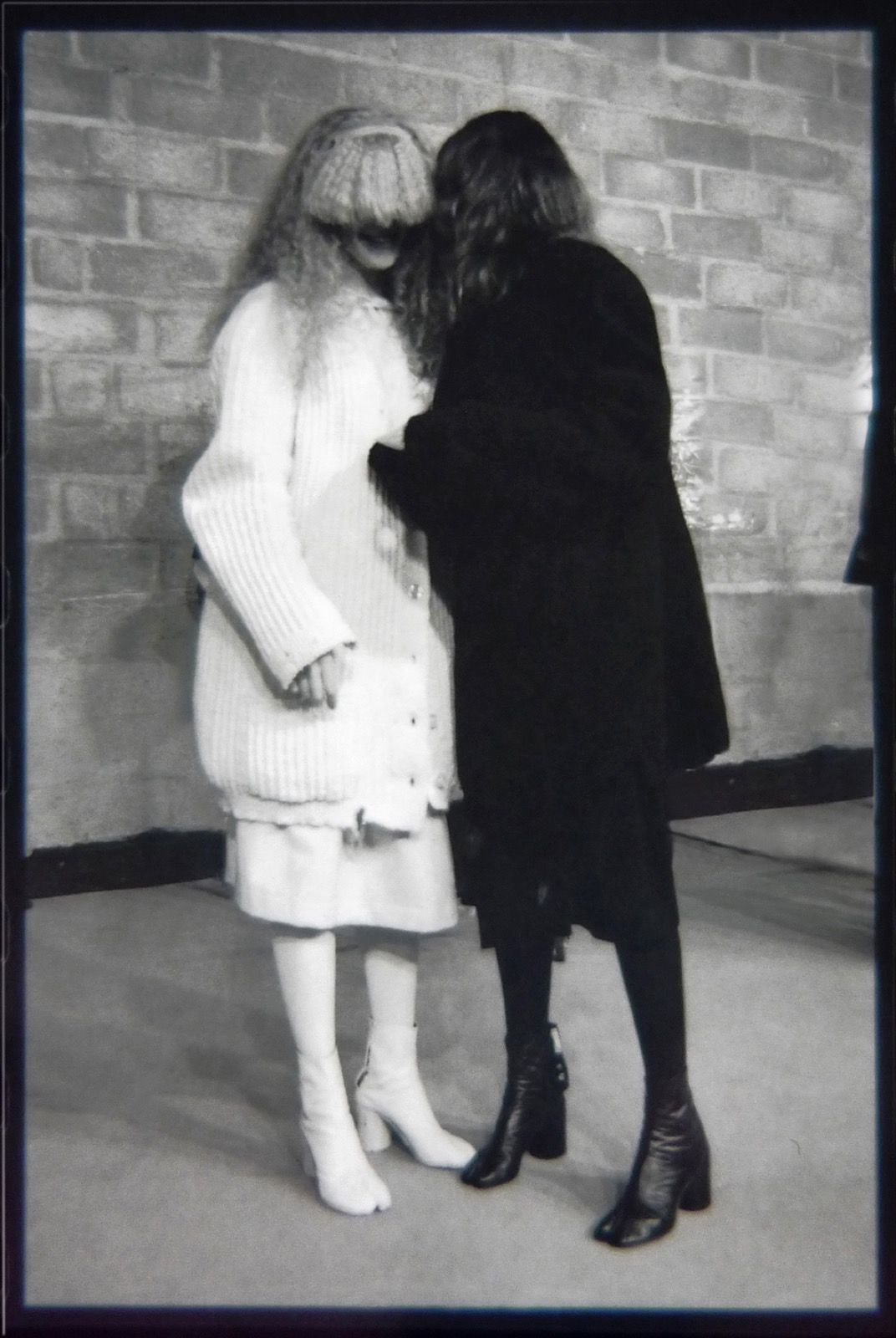

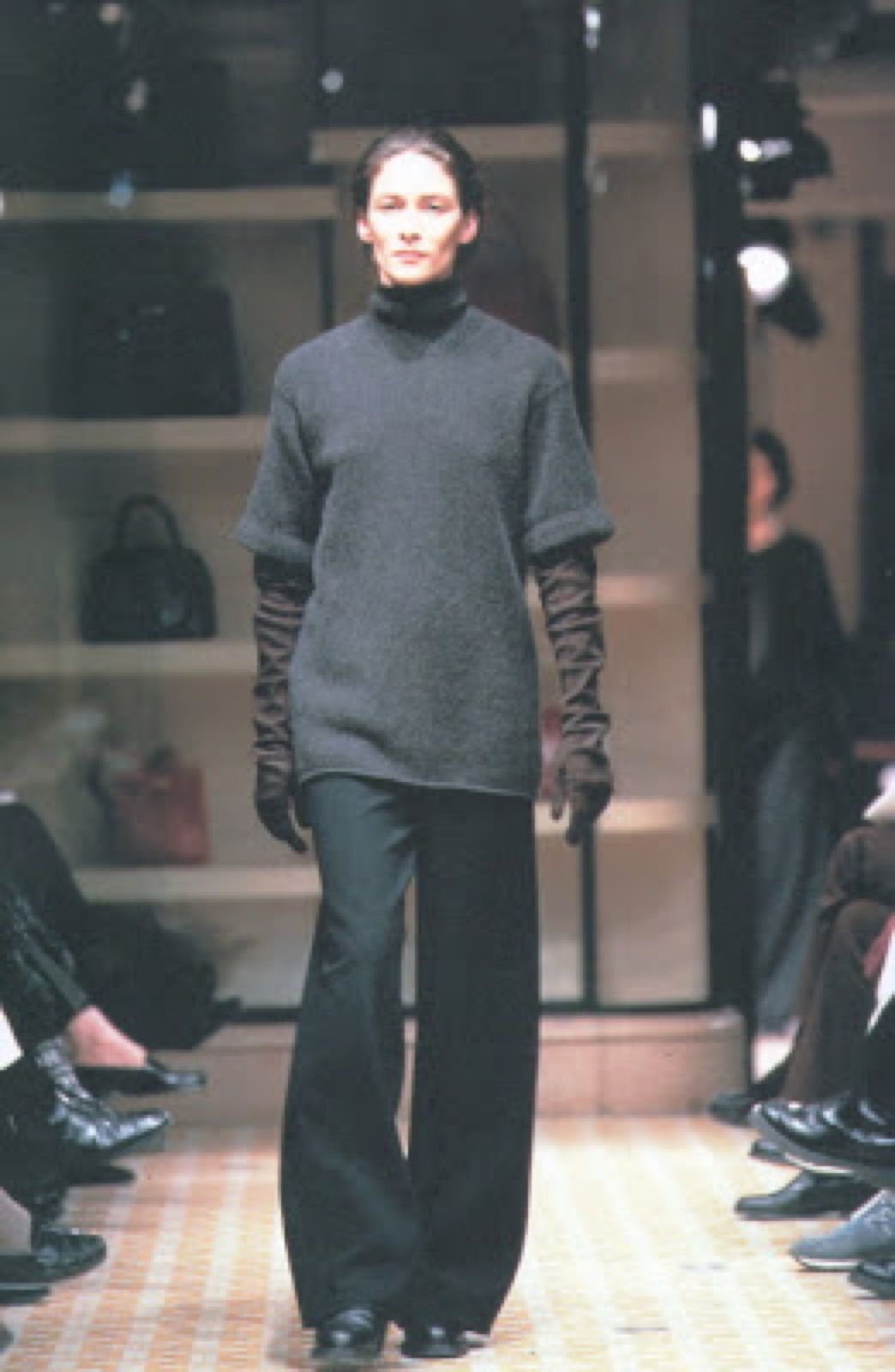

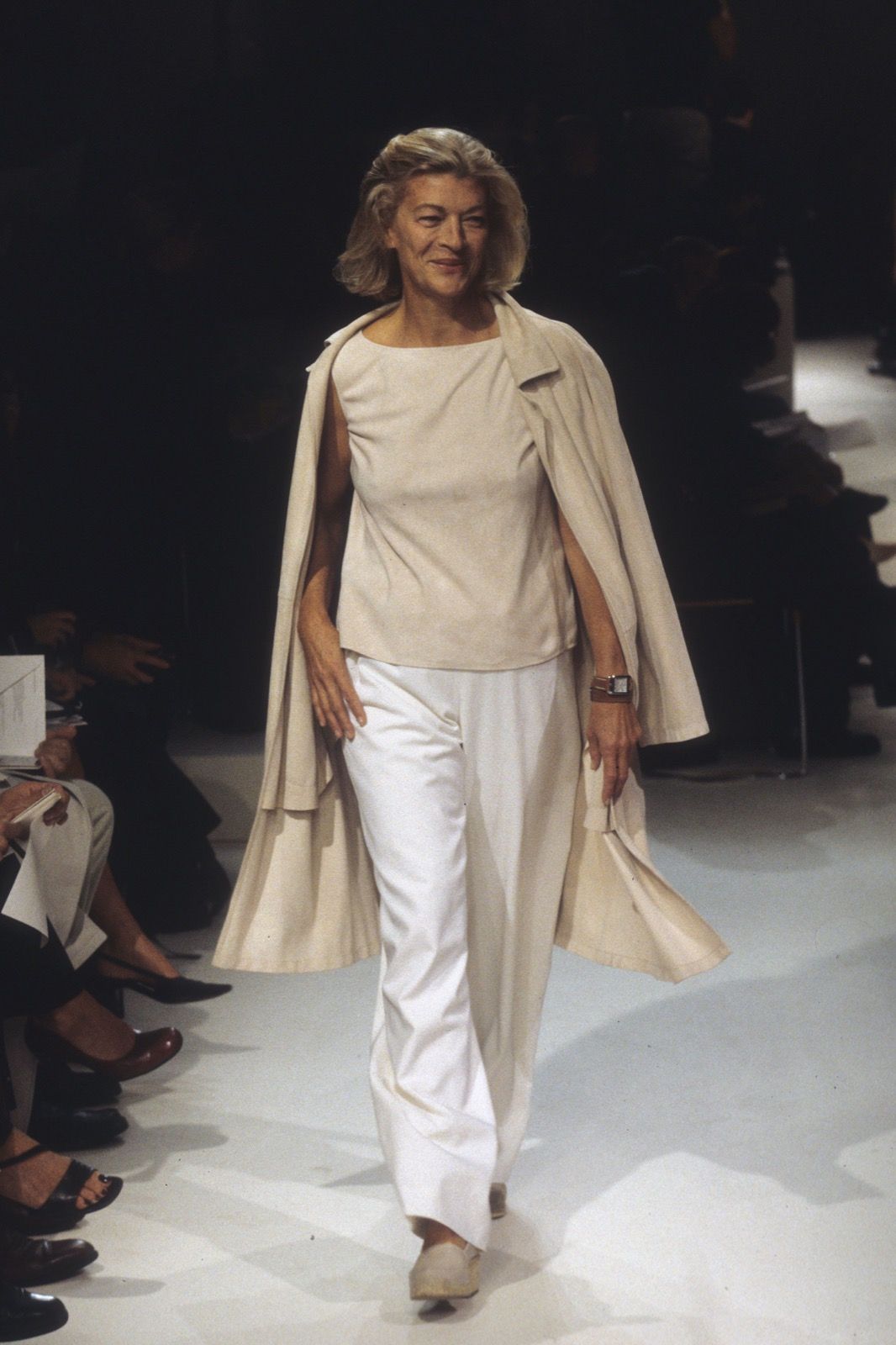

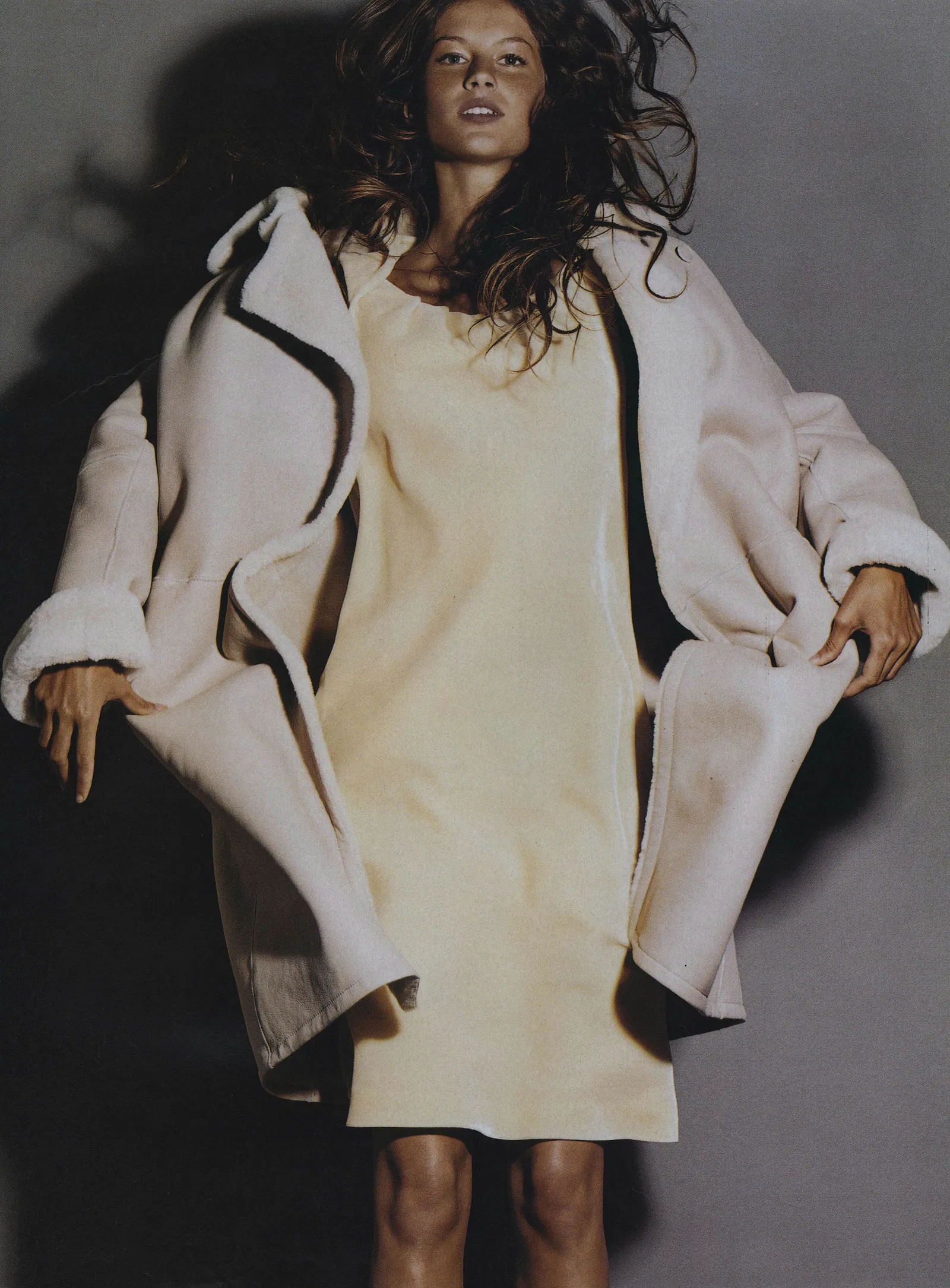

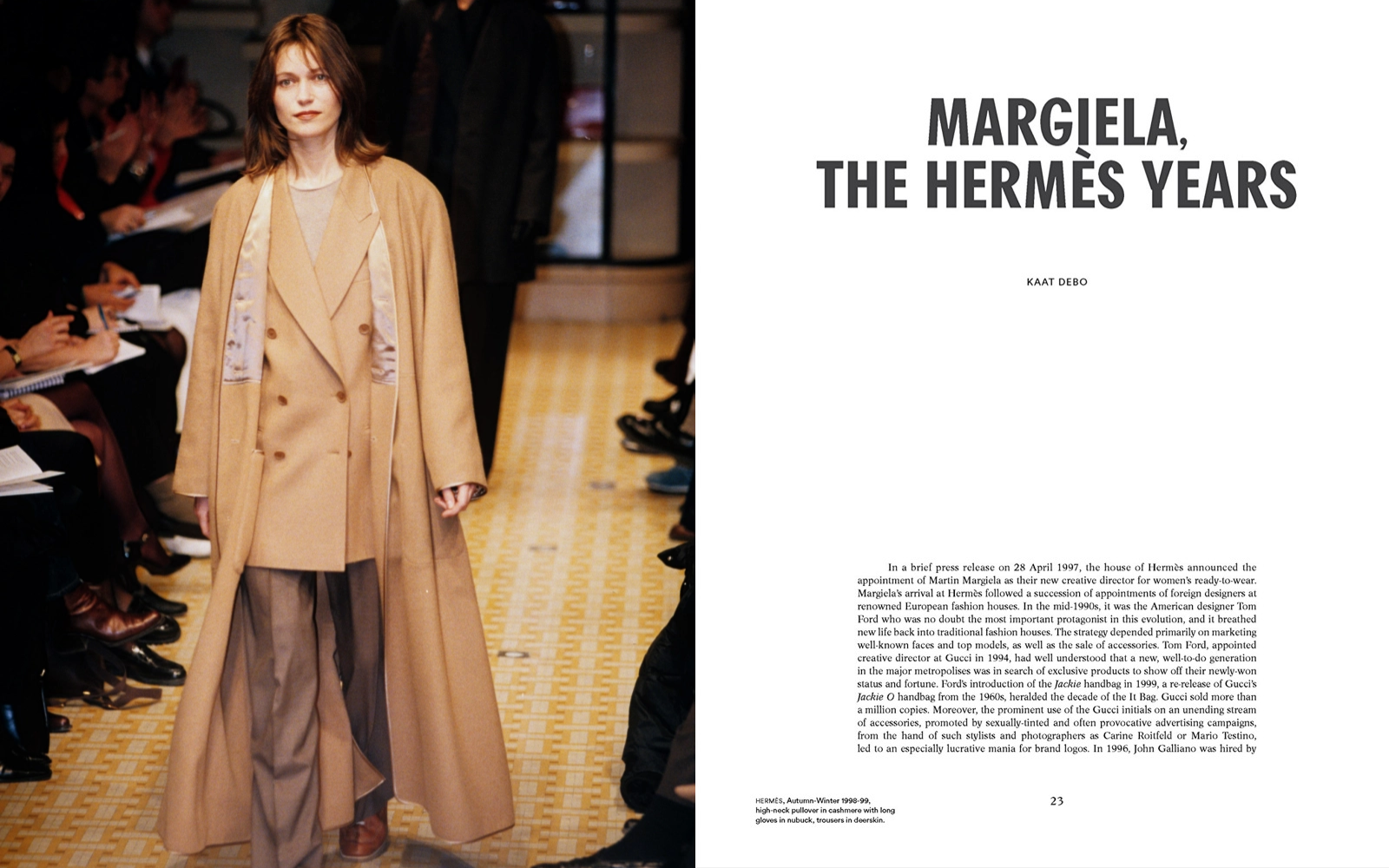

The daughter of Jean-Louis Dumas Hermès had modelled for the Belgian designer several times in the 1990s (unpaid, but in exchange for clothes). When her father asked her one day if she had a name to recommend as creative director instead of Claude Brouet, she answered without hesitation: 'Martin Margiela'. There was no need to convince anyone, there were no mood boards, presentations or business plans, a single lunch was enough to realize that the two personalities, albeit in very different ways, shared a common vision of fashion as synonymous with relaxation, comfort, quality and longevity. And indeed, this unexpected convergence of views was a disappointment to many. The twelve collections that followed under Margiela's direction from 1997 to 2003 were in perfect harmony with Hèrmes' past, a demonstration of the true talent of someone who manages to make the style of such a defined brand his own with respectful mastery. The clothes were characterised by a simple, monochrome yet extremely refined look, an essential luxury that played with the notion of the classic. The clothes Margiela designed for Hermès were very different from those he created for his personal line. They did not cause a stir on the catwalks and were therefore sometimes overlooked at the time.

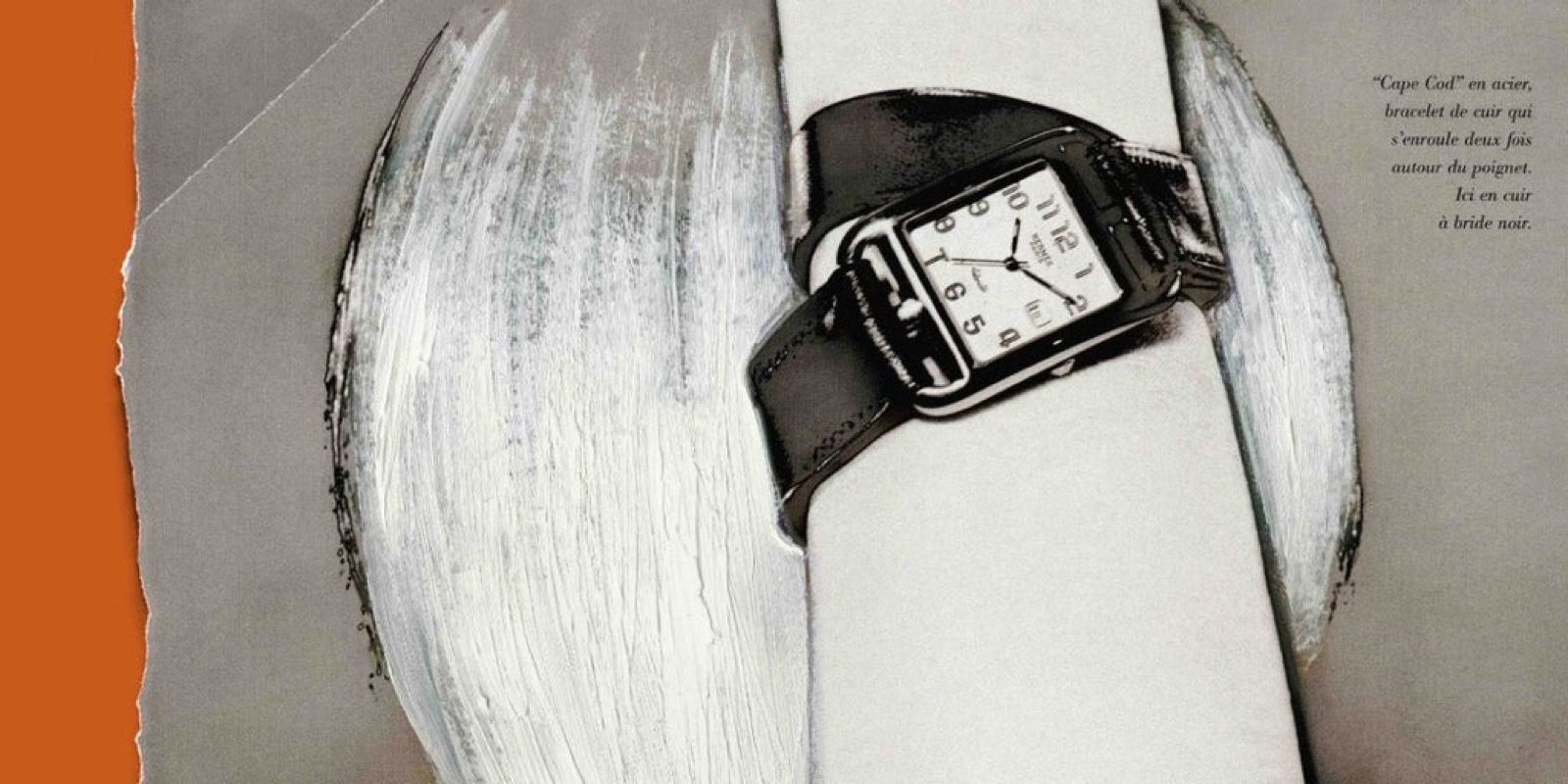

It took time for all the quiet revolutions Margiela made at Hermès to be recognized. A 2017 exhibition at the Momu Museum in Antwerp related Martin Margiela's creations for his eponymous line to innovations for the house of Hermès, through an installation that played with the juxtaposition of Margiela's signature absolute white and Hermès' classic orange. From the famous Vareuse, a blouse with a very deep V-neck, one of the essential components of the "modular" look made of layers and overlaps that the Belgian designer created for the French house, to the convertible trench coats, from the evolution of the twin set to the triple set or the invention of the trikini, Margiela gave an undeniable new élan to the French maison. A legacy that lives on today in the spirit of the brand and in some of the garments and accessories that have become part of the permanent collection: from the Losange scarf, a reinterpretation of the classic silk scarf with yoke, to the iconic Cape Cod watch, a blockbuster characterized by a long bracelet worn as a double loop on the wrist.

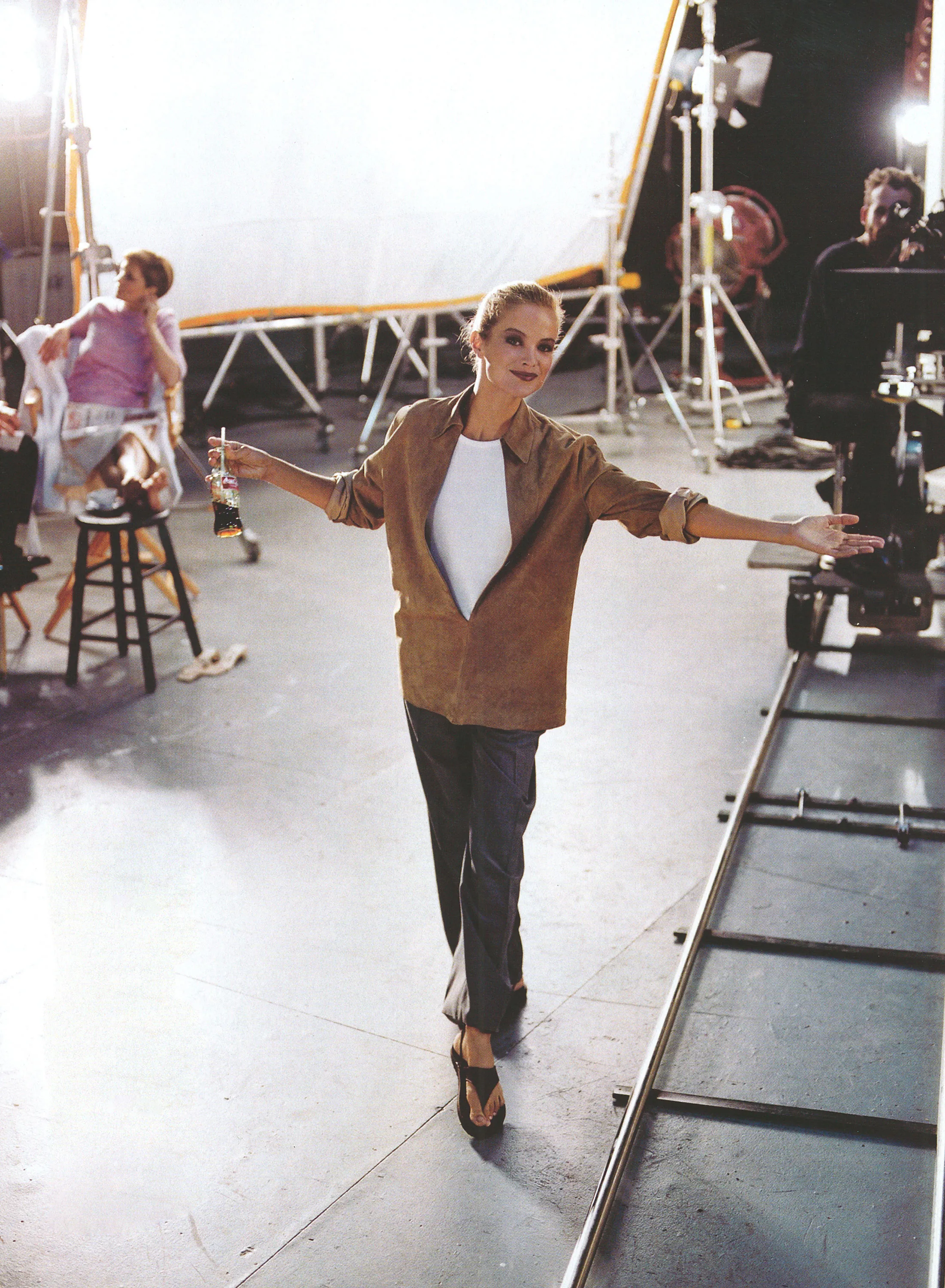

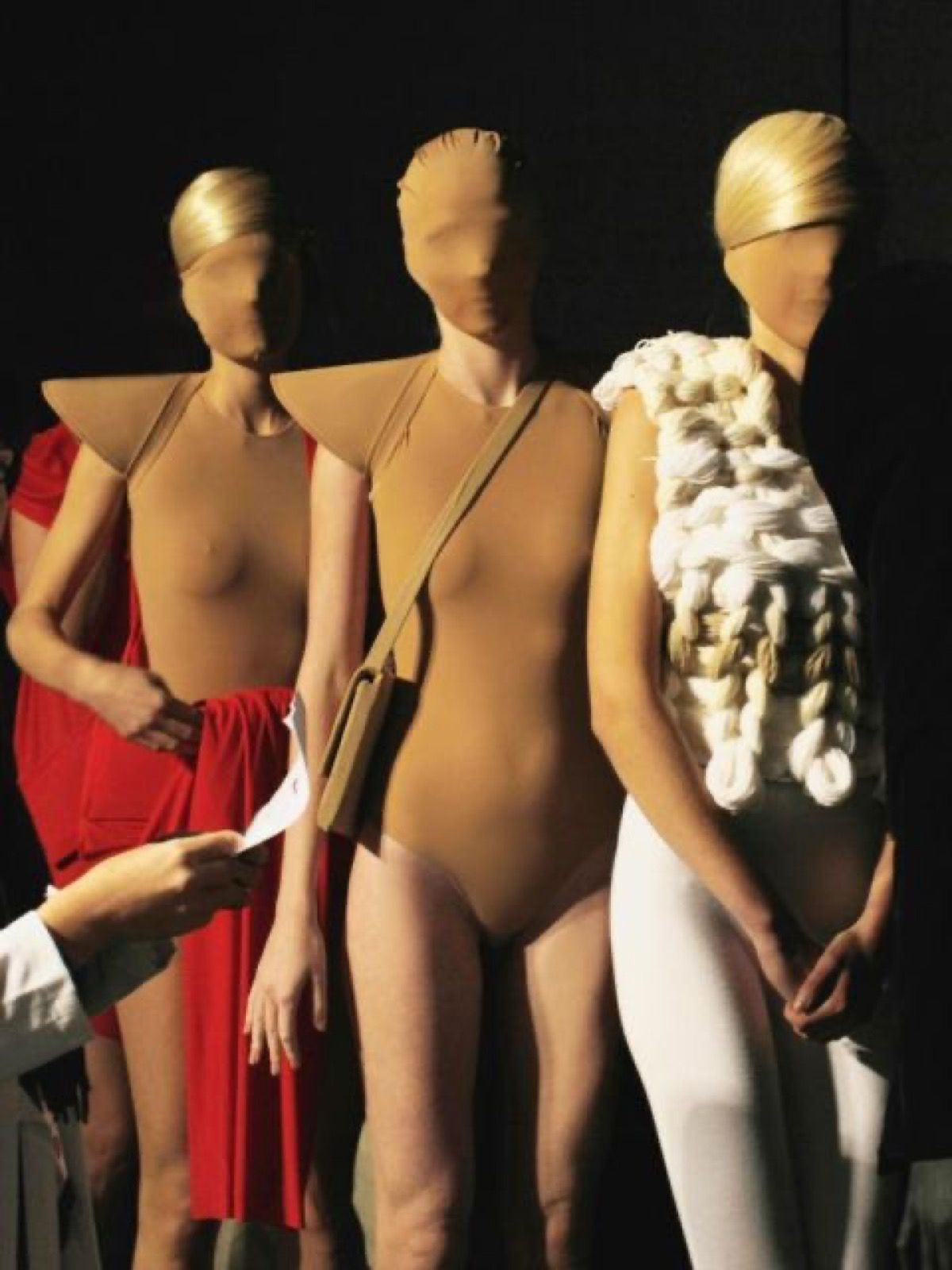

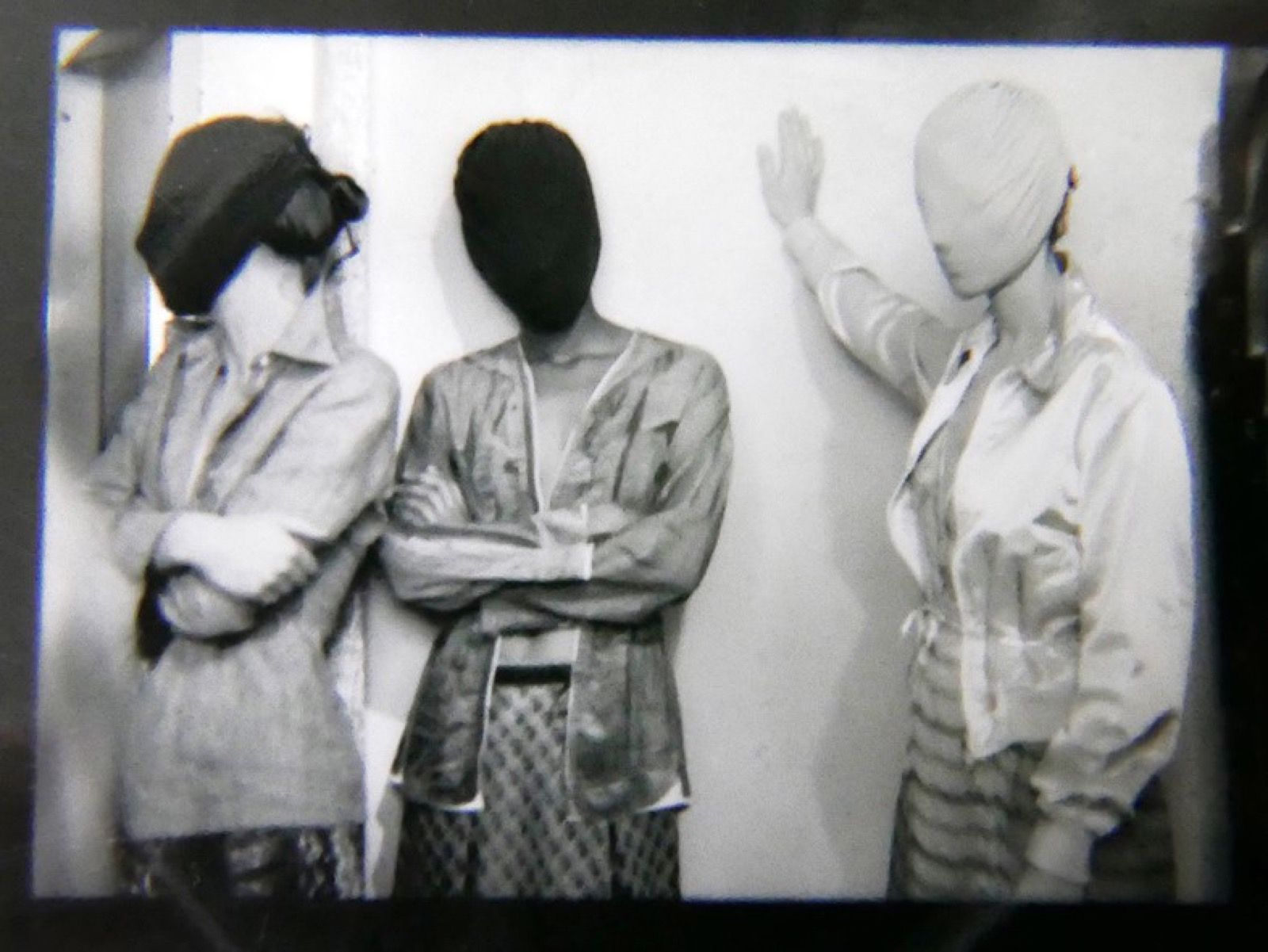

The understanding between Margiela and Hèrmes was also evident in the no-logo philosophy, especially when the designer proposed very simple 6-hole buttons that were hand-sewn into a small, refined H. He did the same with colours, favouring complementary tones over flashy shades: camel, ivory, lead white, taupe (Hermès' legendary 'achromatic'), bronze, stone, alabaster, slate. But the changes were not only in the clothes. For the castings, Margiela always preferred people from the street to professional models, 'real' and often mature women who were truly representative of Hermès customers. The fashion shows took place in the historic Buotique at 24 Faubourg-Saint Honoré, the soundtrack being a male voice giving all the compliments in French that a woman would like to hear: "Tu es fantastique, Tu es charmante, tu es unique...", an idea by Marie-Hélène Vincent to the melancholy background sounds of Erik Satie's Gymnopédies.