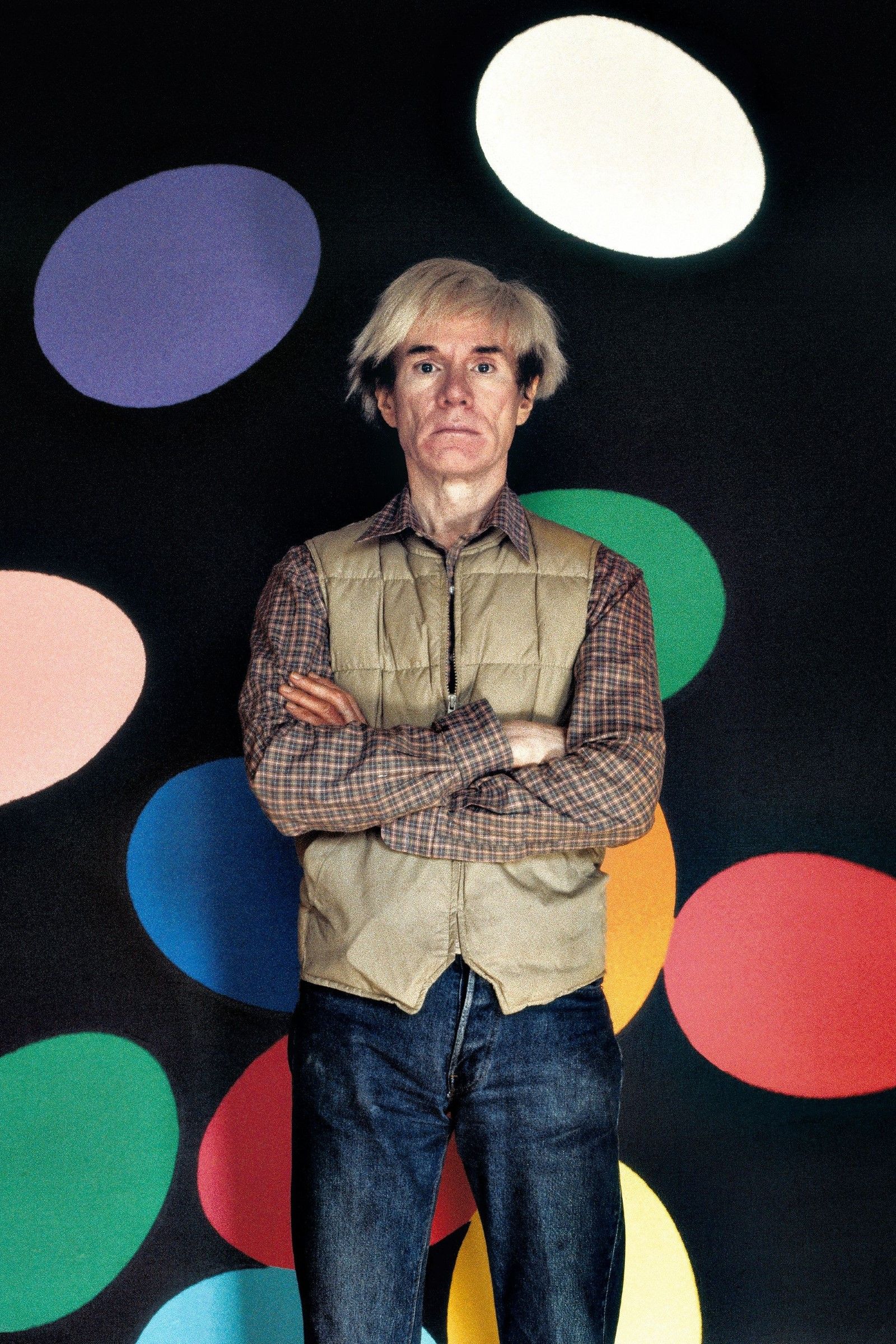

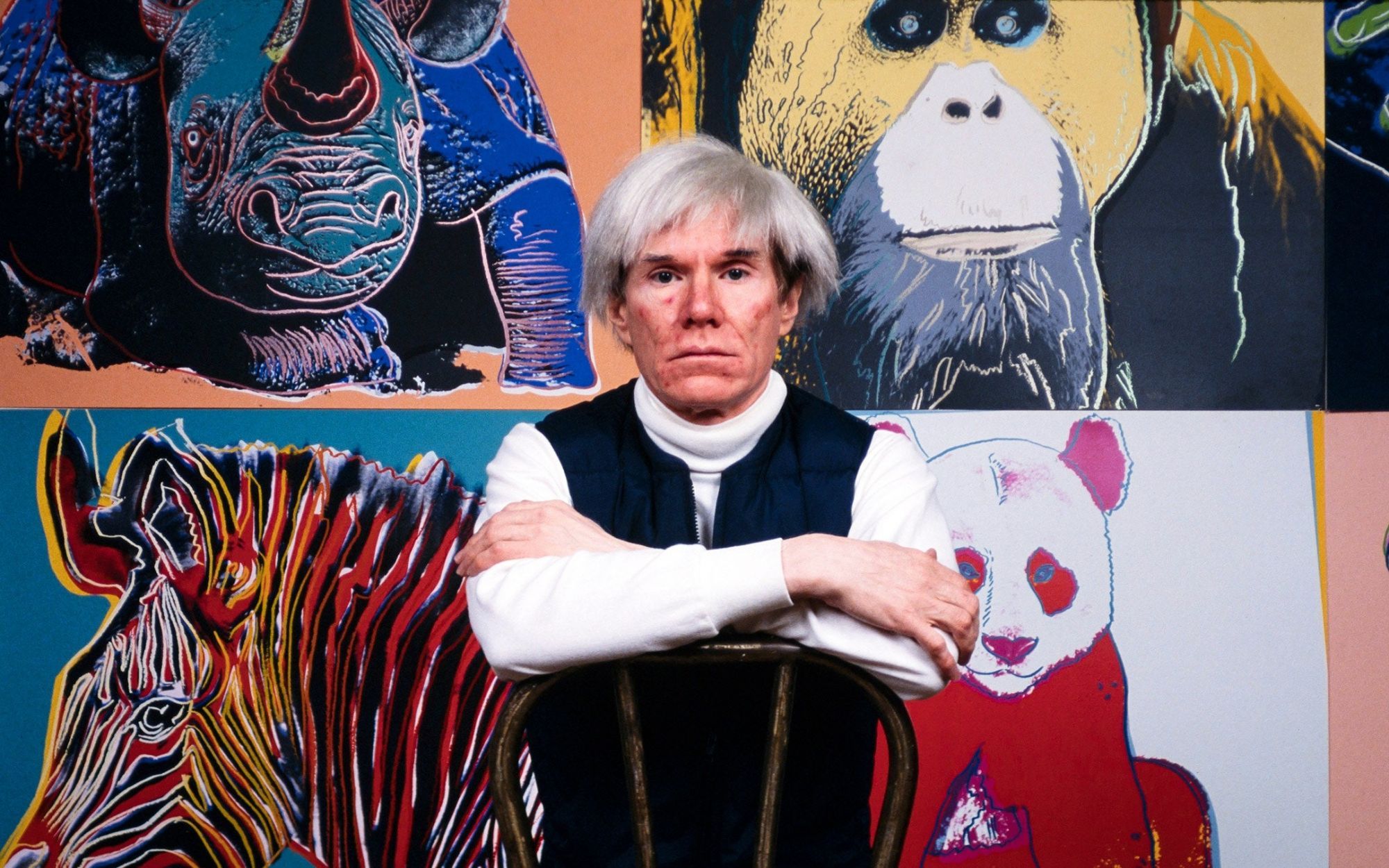

Is fashion celebrating or exploiting Andy Warhol? Reflections on a ubiquitous artist

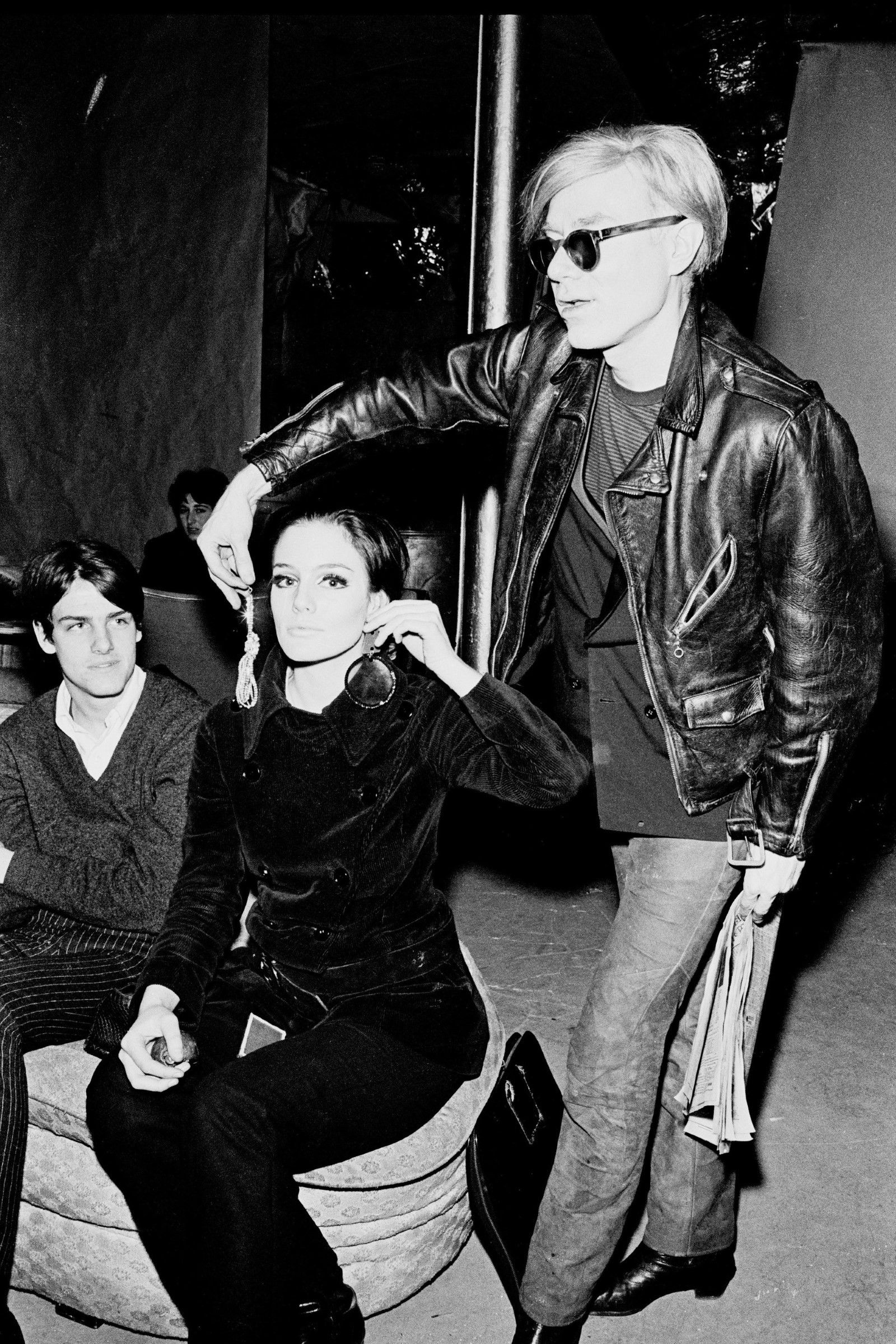

«Business art is the step that comes after art. I started as a commercial artist, and I want to finish as a business artist. Being good in business is the most fascinating kind of art. [...] They’d say “money is bad” and “working is bad”. But making money is art, and working is art - and good business is the best art», Andy Warhol once wrote in his diaries. A phrase that makes one think a lot - especially in an era like ours divided between commercialism and the uniqueness of art. All notions that Warhol had thrown out the window, declaring himself a superficial lover of consumerism, of the commercial repeatability of industrial products, of what the culture of the time had of pop. And seeing the way in which fashion today makes use of Andy Warhol and his art, that is, transforming his artistic legacy into a series of easily sellable graphics, one might wonder whether the artist would consider himself more celebrated or exploited by industry. Warhol, after all, was infatuated with celebrity, with popular icons, with the smiling commerciality of Hollywood stars - he might have loved our age, the digital, Instagram and probably even the idea of fast fashion. We're talking, after all, about the same artist who declared that the greatest thing about the capitals of the world was McDonald's. «What’s great about this country is that America started the tradition where the richest consumers buy essentially the same things as the poorest», he wrote once. «You can be watching TV and see Coca Cola, and you know that the President drinks Coca Cola, Liz Taylor drinks Coca Cola, and just think, you can drink Coca Cola, too. ».

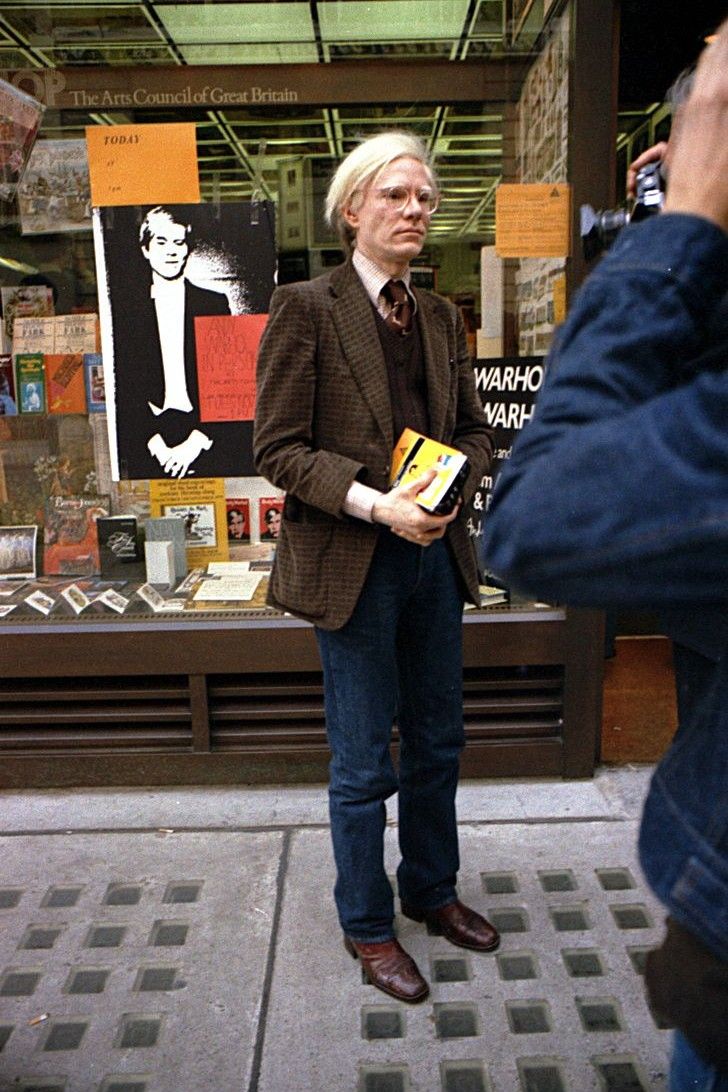

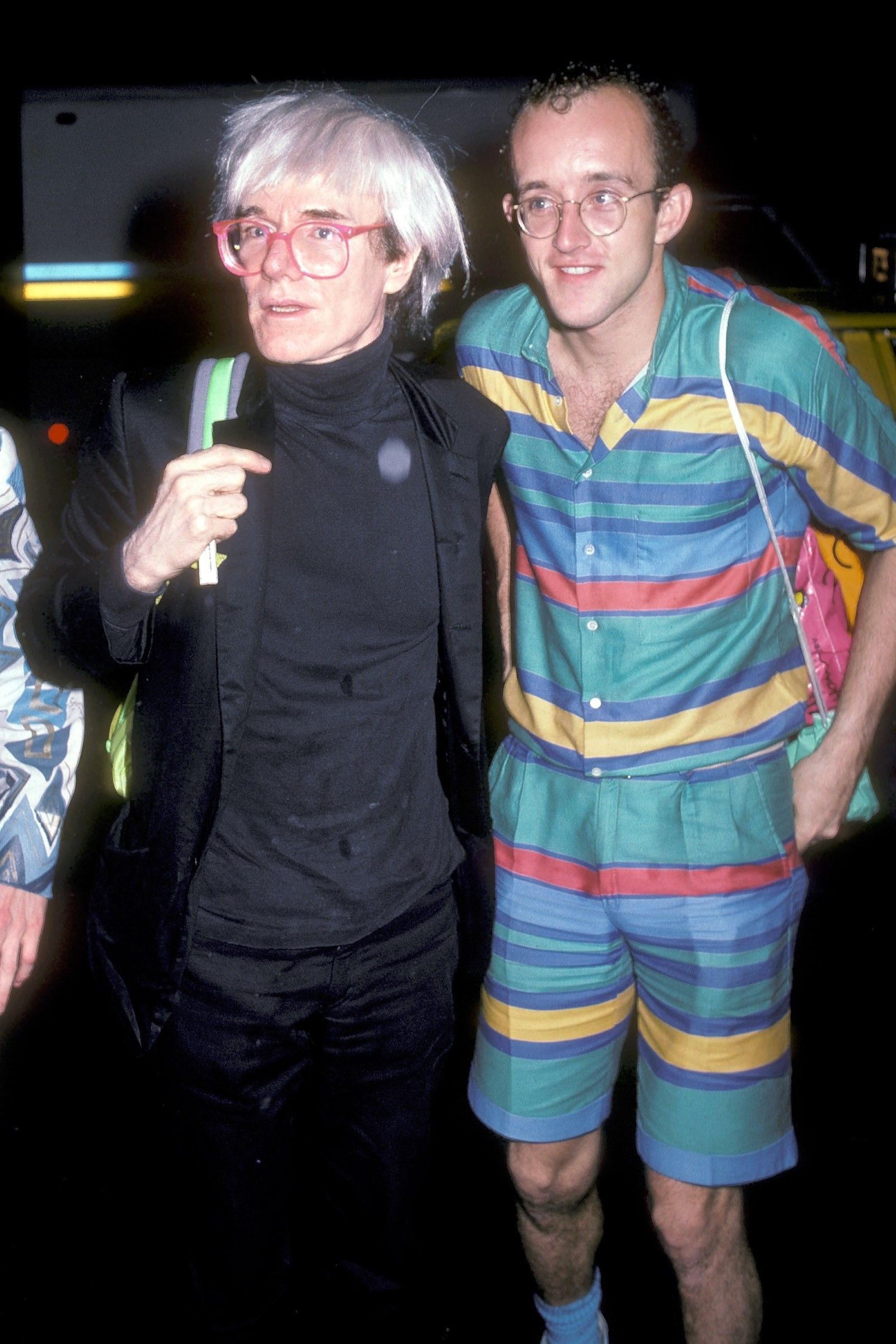

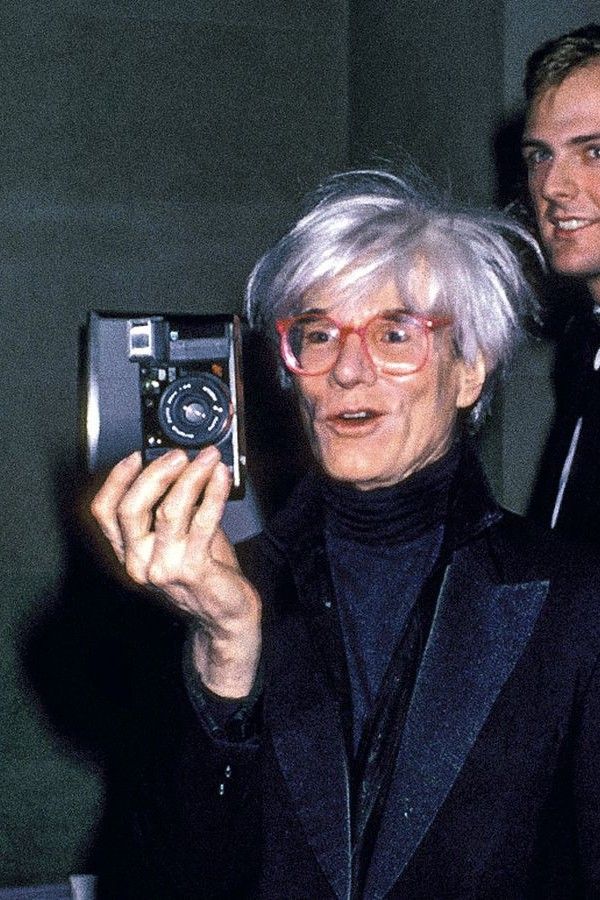

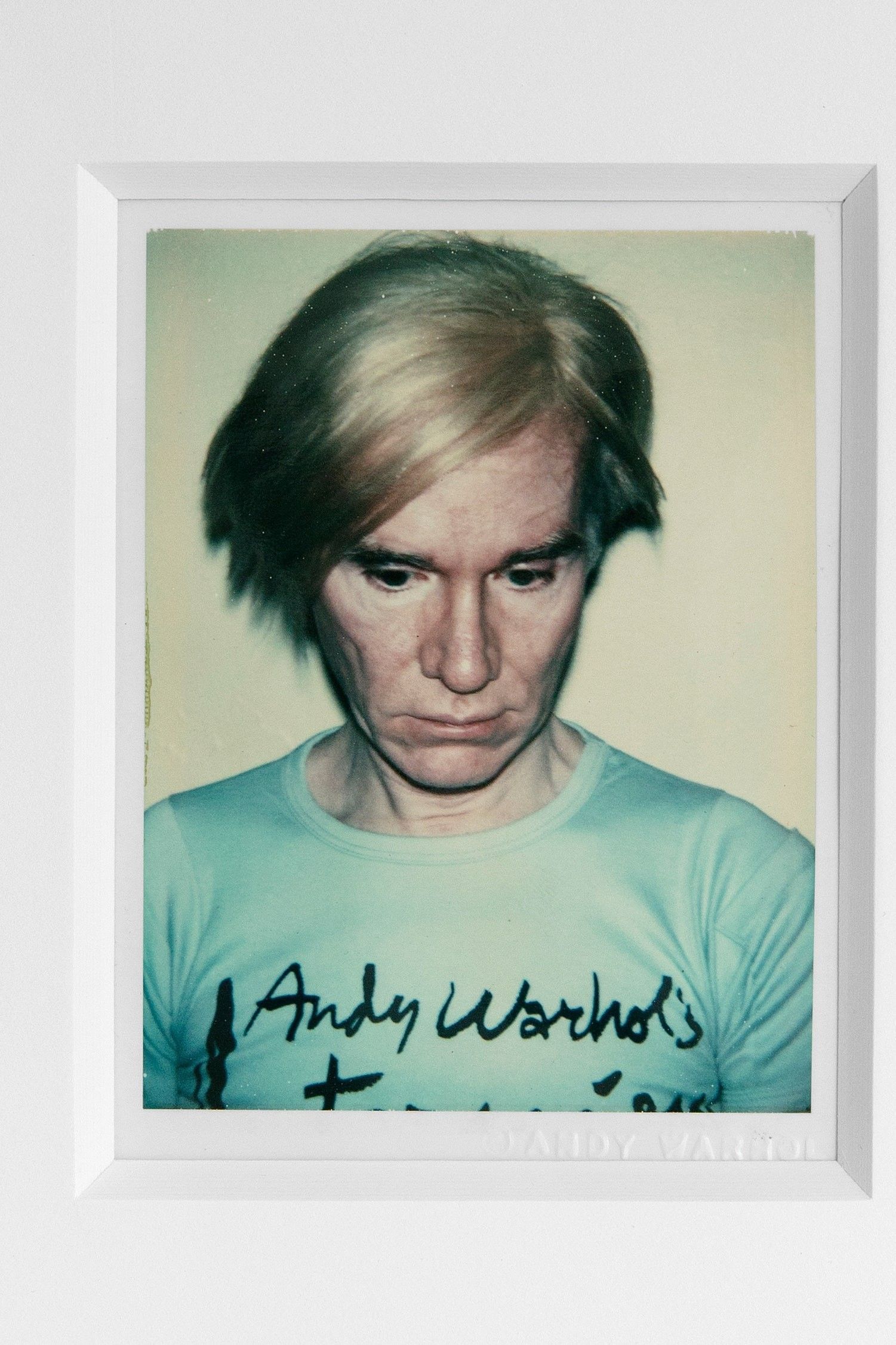

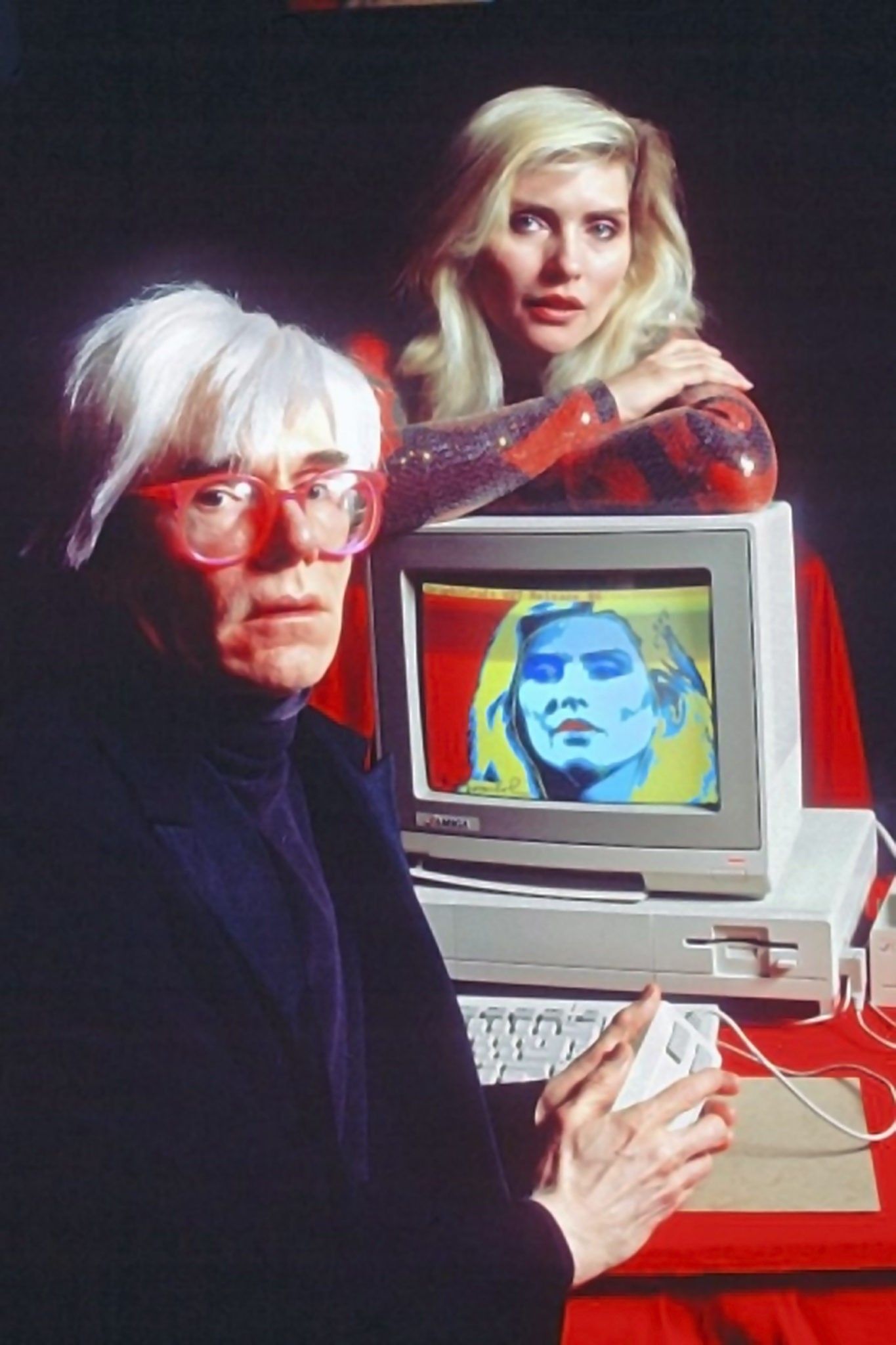

In the world of fashion and merch, Andy Warhol's name has appeared over the years on products by Vans, Eastpak, Medicom Toy, Supreme, Zara, Uniqlo, Retrosuperfuture, Comme des Garçons, Pull & Bear - even Bottega Veneta recently capitalized on Warhol's prestige by showing the public the Polaroids the artist took at the brand's New York boutique in the 1980s and by returning to talk about the Bottega Veneta Industrial Videotape short film. It's not just fashion: there are skateboards, furnishings, puzzles, one-off BMW models, vinyls, Burger King ads, perfumes. Theoretically, Warhol might have seen this commodification as a kind of transcendence, a consumerist apotheosis. But in an era in which even Netflix offers us with its series, The Andy Warhol Diaries, a detailed exploration of Warhol's artistic work in which his voice has been recreated by artificial intelligence to read his private diaries "live", it is inevitable to feel a little bitter to see the cultural relevance of this artist flattened and used to sell yet another cheap t-shirt, yet another gadget, yet another fundamentally useless object. All the more so because all these collaborations use Warhol's name within the limits of the fame of his works, without attending at all to the true, great and sometimes "scandalous" heritage of his complete catalog. In fact, Warhol's works went far beyond tomato soup, bananas, and Marilyn Monroe and tackled topics that were impossible to publicly talk about at the time such as social alienation, the death penalty, HIV, LGBTQ+ culture, prostitution, drugs - all aspects of a multifaceted artist that can't be printed on a pair of canvas sneakers or the back of a hoodie and that are not only less immediately commercial but still make you wonder how much our contemporary mass society is ready to deal with them. And therein lies the true limit of the commodification that has been made of the artist and his work.

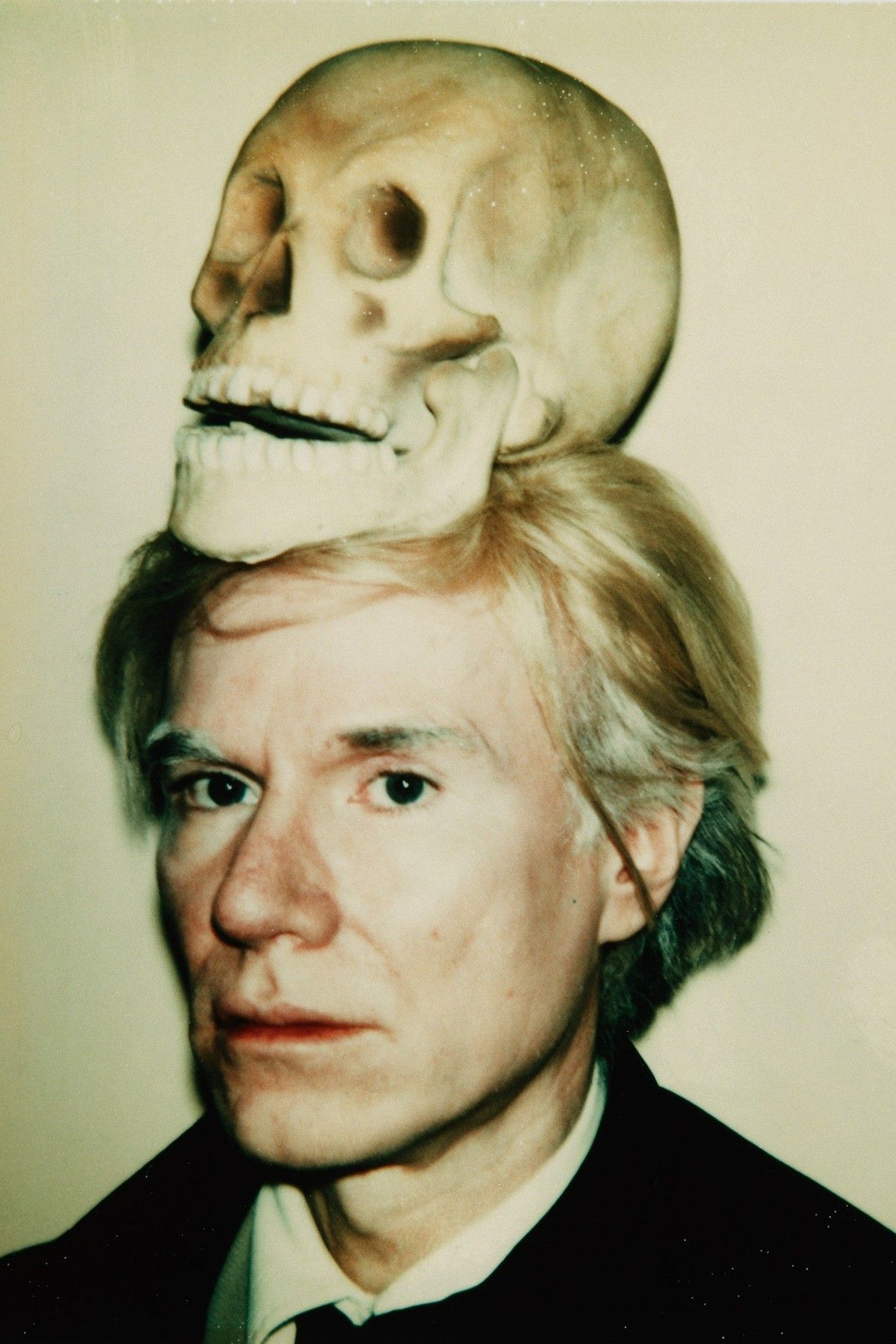

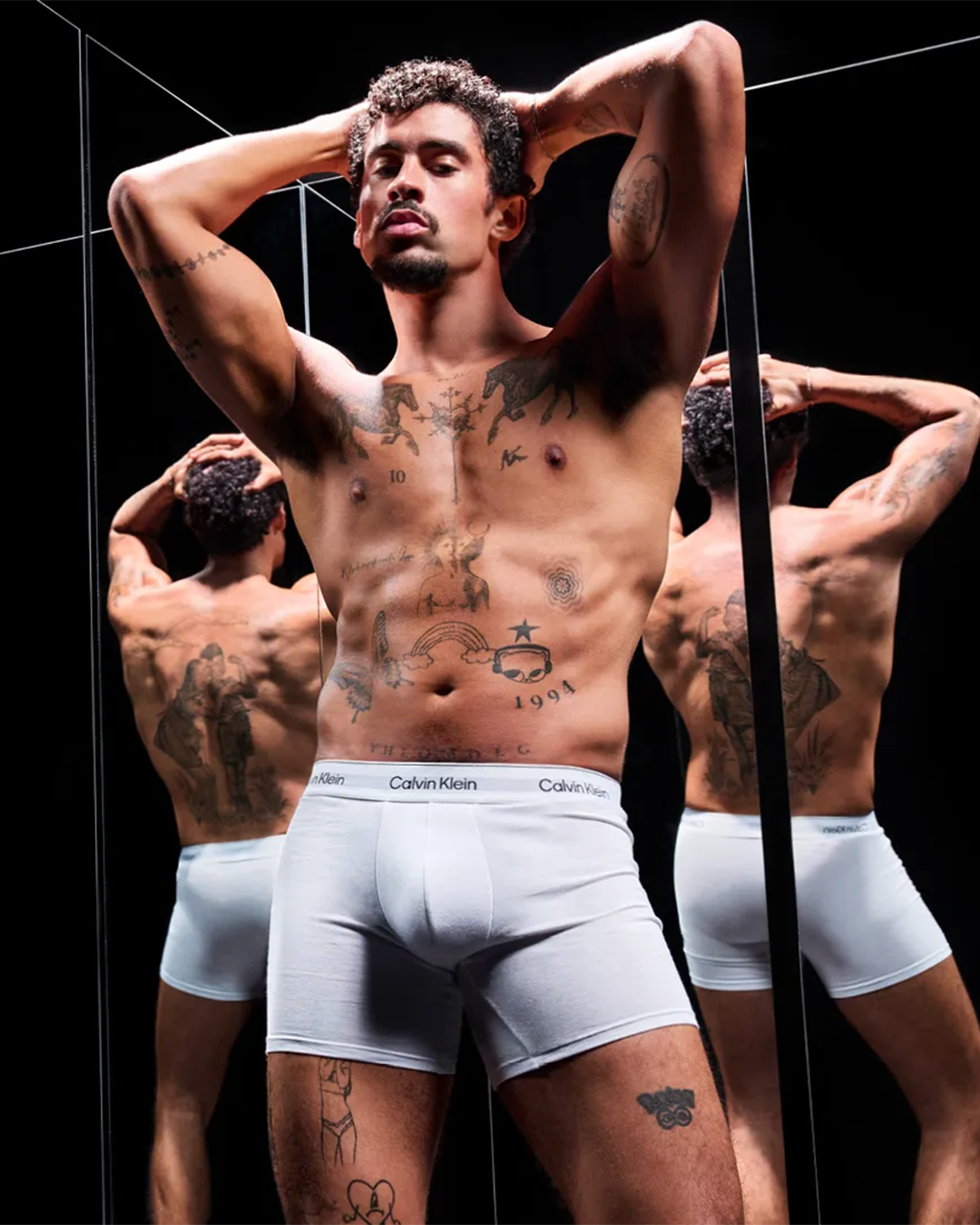

Perhaps the only example of intelligent use of Warhol's work in fashion was that of Raf Simons during his brief but brilliant season at the helm of Calvin Klein. The collaboration between The Andy Warhol Foundation and Calvin Klein 205W39NYC for the SS18 collection was more than fortuitous: not only did Raf Simons recontextualize Warhol's work in a multidisciplinary sense, between sets designed by Sterling Ruby and his own designs, but he sank his gaze into the more melancholy and macabre side of the artist's work by printing his photos of car crashes and electric chairs on the clothes, mischievously placing frames from the film Kiss on underwear and portraits of Stephen Sprouse (one of the first designers, along with Halston, to bring Warhol's language into fashion) but also indirectly quoting the artist by covering some wool coats with plastic - a touch, it must be said, that is a bit of a trait d'union between the languages of Simons and Warhol. «American horror, American dreams», explained Simons to Vogue, after having mixed in the same collection citations to The Shining, Carrie and Dennis Hopper. Simons' work with this collection was significant precisely because he didn't commodify Andy Warhol for himself, repurposing his more "easy" and recognizable side, but contextualized his works in a larger universe of references to paint a portrait of American culture as seen by a European. To date, no other designer has interpreted Warhol's art as effectively.

To answer the title question, we could say that fashion is both celebrating and exploiting Andy Warhol - while skewing slightly to the exploitative side. Perhaps Andy Warhol would have enjoyed more being commodified rather than seeing his private life dissected through a thousand films and a thousand documentaries. After all, as Vanessa Friedman wrote in 2018, in the midst of the Trump era, we live in a profoundly Warhol-ian age:

«We are living in a Warhol moment inside a Warhol moment inside a Warhol moment — in a country run by the most Warholian president we have ever had, at a time when Instagram has made everyone an influencer for 15 minutes, during a year where the Warhol body of work is being celebrated as never before».