Goblin mode is not what you think it is Social trivia or celebration of depression?

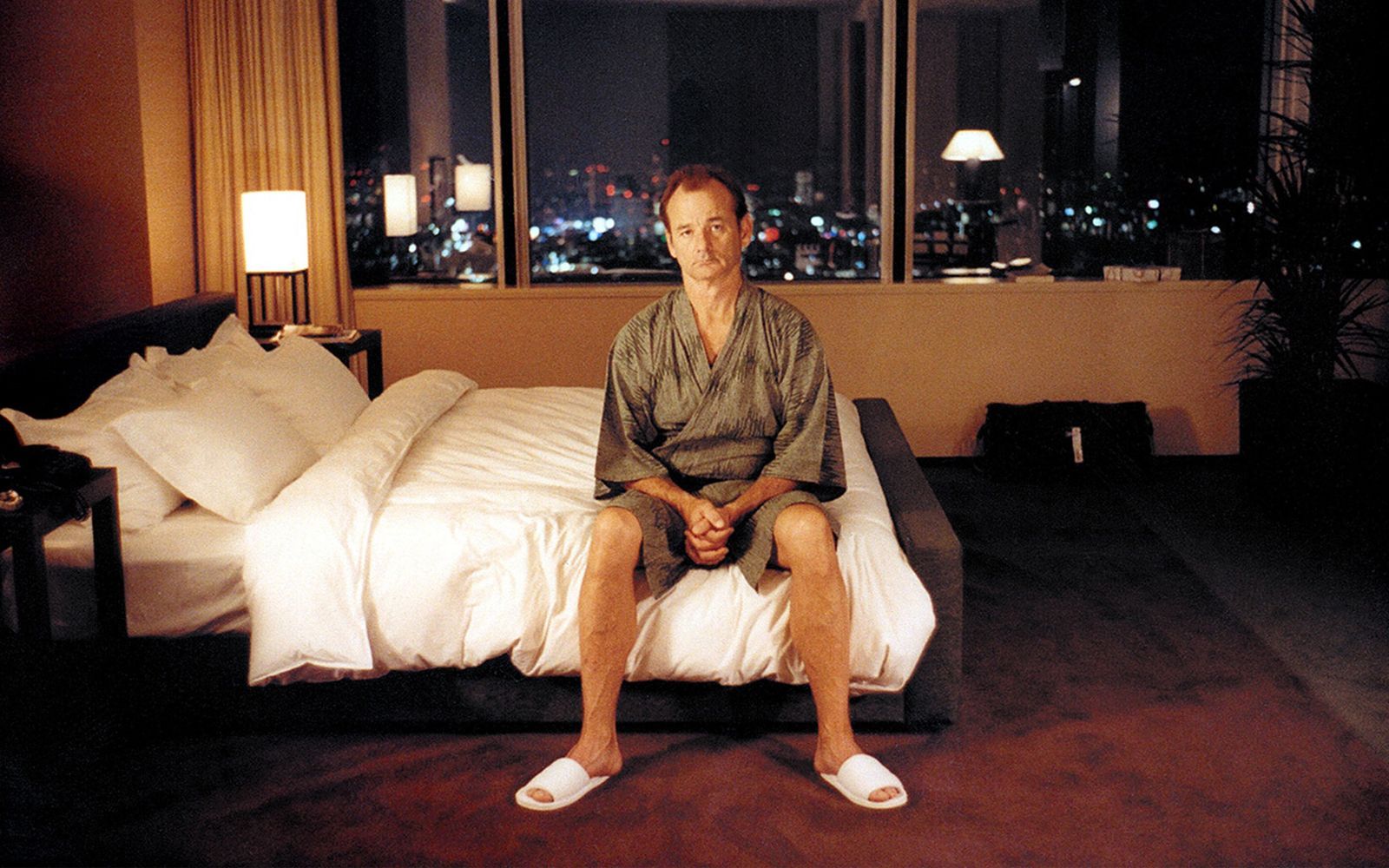

The new hashtag that is racking up views on TikTok, Twitter and Instagram is #goblinmode, fueled by photos of Zendaya dragging herself across the floor of her house in Euphoria, candid videos of roommates in pajamas rummaging through messy apartments, various humorous skits about staying in on a Saturday night drinking beer and watching trashy movies, and so on. The idea of goblin mode is actually a narrative frame for different contents that all refer to the idea of "letting yourself go when you're at home" without caring about physical appearance, outfit, makeup or skincare, diet and so on. Which is, on a social culture level, a response to those motivational videos in which super-healthy guys clean their man cave and sneaker closet or girls brag about waking up early and drinking a purifying smoothie. On a human level, however, one could interpret the spread of the trend as the extreme reaction to a world so chaotic, problematic and unpredictable that people simply decide to lock themselves in the house, go out for groceries or the occasional walk around the block and talk to their cat. As many have already pointed out, the trend touches on (albeit superficially) the topic of mental health by questioning social expectations and the culture of productivity, celebrating self-indulgence but also highlighting a certain nihilism that a meme once summed up in the motto: «Death is coming. Eat trash. Be free».

@horrible.glitter Reply to @bratssica #thatgirl #girlboss #elizabethholmes Love You So - The King Khan & BBQ Show

Beyond the trend itself the emergence of the idea of goblin mode highlights two phenomena through which the social media discourse is articulated today: the first concerns the urge of inventing increasingly disparate names to explain phenomena that have existed for years; the second concerns instead the increasingly polarized view that one has of mental health through the lens of social. The first phenomenon is a direct derivative of the system of hashtags, which must be short and hyper-recognizable, and which in recent years have multiplied following the multiplication of the number of so-called "aesthetics" on social media such as TikTok - terms that actually typify people's ways of being, summarizing states of mind or complex imaginaries in single words. Which is not a bad thing in itself but tends to shift and rewrite the meanings of things. One possible example is the use of psychological terms related to disorders such as anxiety or depression to describe normal emotional states with the result that people say they feel depressed but in reality they are just sad. One possible example is the use of psychological terms related to disorders such as anxiety or depression to describe normal emotional states. A term like social anxiety, for example, has gone from describing a real psychological problem to any unpleasant situation - with the result of bringing into the same psychologist's office both those who are in an unpleasant situation but do not really suffer from a chronic disorder and those who are seriously affected by hikokomori syndrome or agoraphobia - two possible scientific aliases of goblin mode.

you’re not “going goblin mode” you have clinical depression

— trash jones (@jzux) March 5, 2022

A simple but telling tweet illustrated this issue of names well «You’re not “going goblin mode” you have clinical depression». This statement highlights, on the one hand, the fact that creating a funny and memorable name for a certain mood ends up justifying its symptoms, making them normal and acceptable and therefore preventing their resolution; and, on the other hand, the more abstract risk of trivializing psychological problems by offending with humor those who really suffer from depression and have difficulty socializing and getting out of the house. To be fair, however, it must be said that a lot of online content related to the idea of goblin mode is not used seriously to discuss depression or to describe ongoing mental conditions - depression manifests itself superficially as the symptoms of goblin mode but is something profoundly different and more serious. The implicit risk of course lies in the generalization of justifying giving up as something liberating in an uncodified and uncritical way and preventing that basic dialectic between obstacle and overcoming it that is the key to people's growth.

As mentioned, then, the insistence on goblin mode on social as a reaction to the "positive" narrative coming from influencers large and small with videos that follow them through the various steps of their routine as they methodically clean their homes, move through minimal-perfect furnishings, get dressed, pack and shower. This storytelling doesn't focus on the "perfect life" but on the pleasant sense of order and discipline that, ideally, is the metaphorical garnish for a well-trained body, an immaculate diet and a closet full to bursting with Louis Vuitton clothes and sneakers. The unhinged and opposite reaction is therefore radical, it is the chaos of goblin mode, of cheese snacks at two in the morning, of dishes left dirty accumulated from two days, of hair ruined by the pillow. But what's missing from this narrative (which, incidentally, lends itself poorly to high-intensity storytelling on social) is a heartfelt account of people's daily lives that oscillates between the extremes of #cleaningmotivation and #goblinmode - and it's precisely because of the lack of mediated, tempered storytelling that discussion of mental health issues via social results in such an incomplete, sloppy, and simplistic, and therefore pointless, narrative.