Candyman and the gentrification of black culture The importance of black ownership in the world of art and fashion

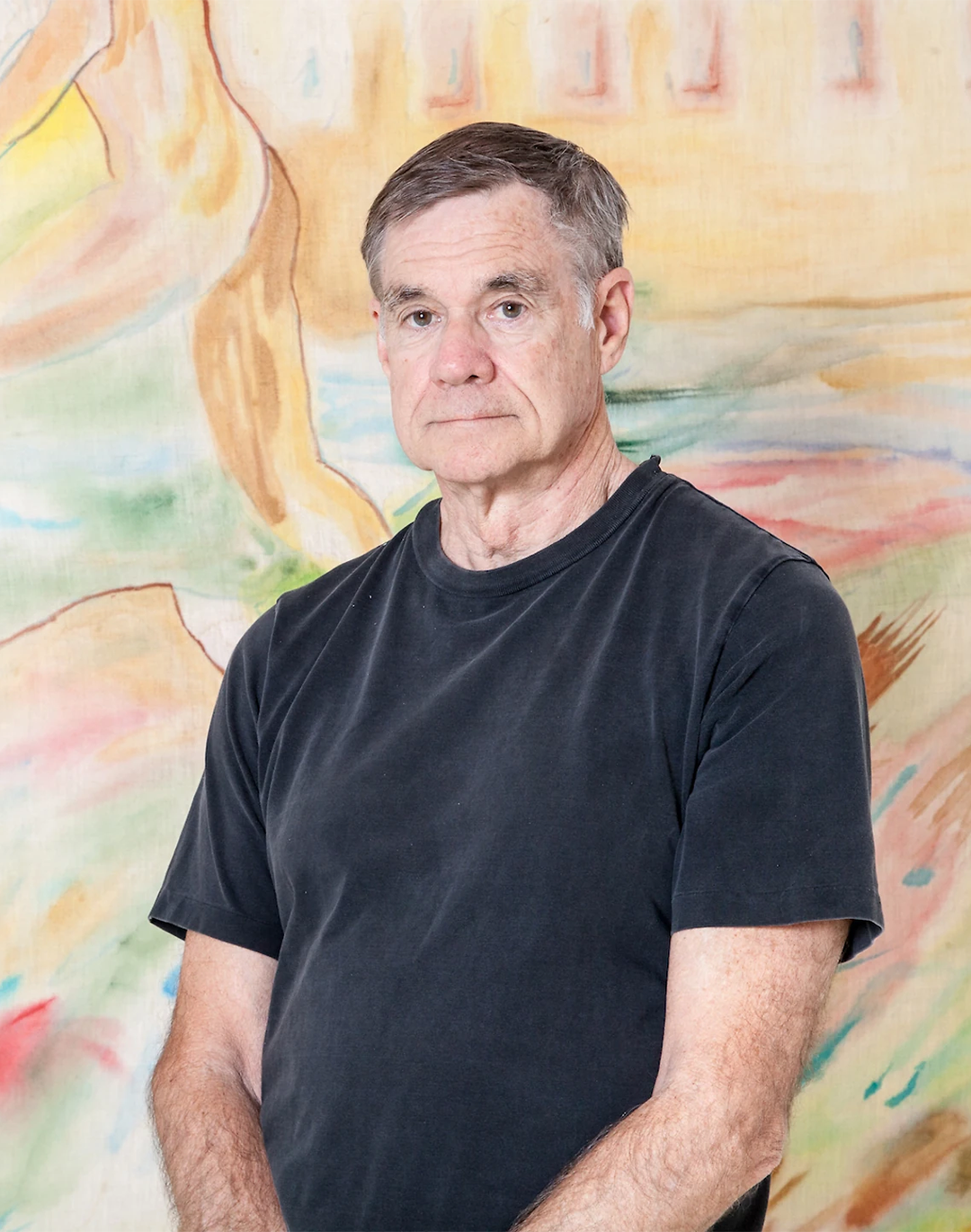

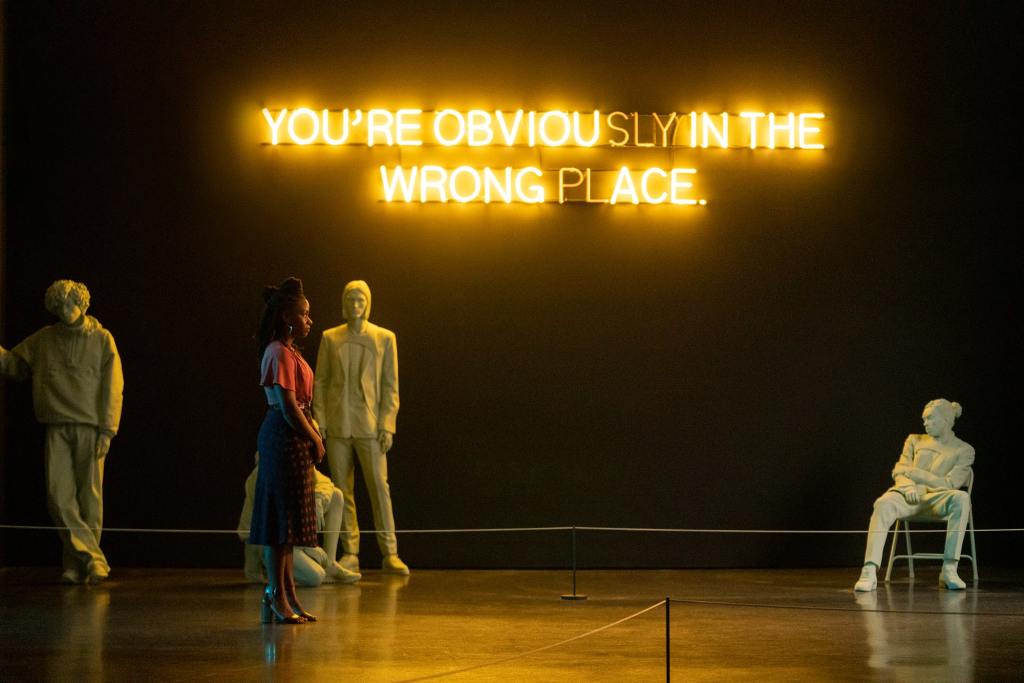

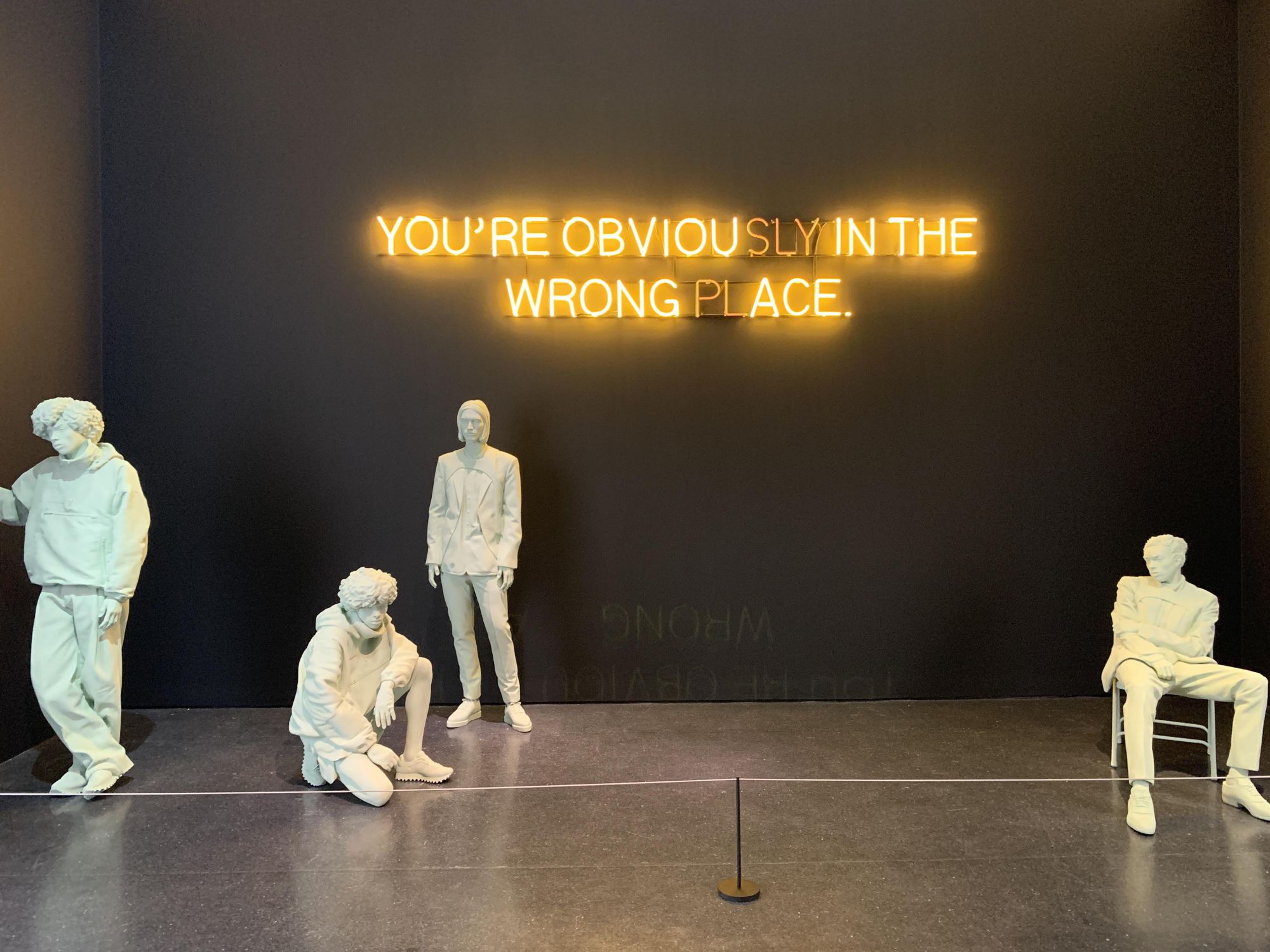

What happens when African Americans gentrify a neighborhood? Where is art positioned in the process of re-appropriation of spaces? What happens if you try to use black art as commodities to increase the value of your brand? When Brianna Cartwright, partner of Anthony McCoy - the new protagonist of Candyman - and gallery owner, is invited to the MCA in Chicago to discuss potential working synergies, she ends up talking about a possible exhibition of her partner in front of the work that perhaps most of every other represented the gentrification of modern art: a giant luminous neon depicting the phrase "You're obviously in the wrong place", part of Virgil Abloh's installation for his personal "Figures of Speech" held right in the museum of his hometown.

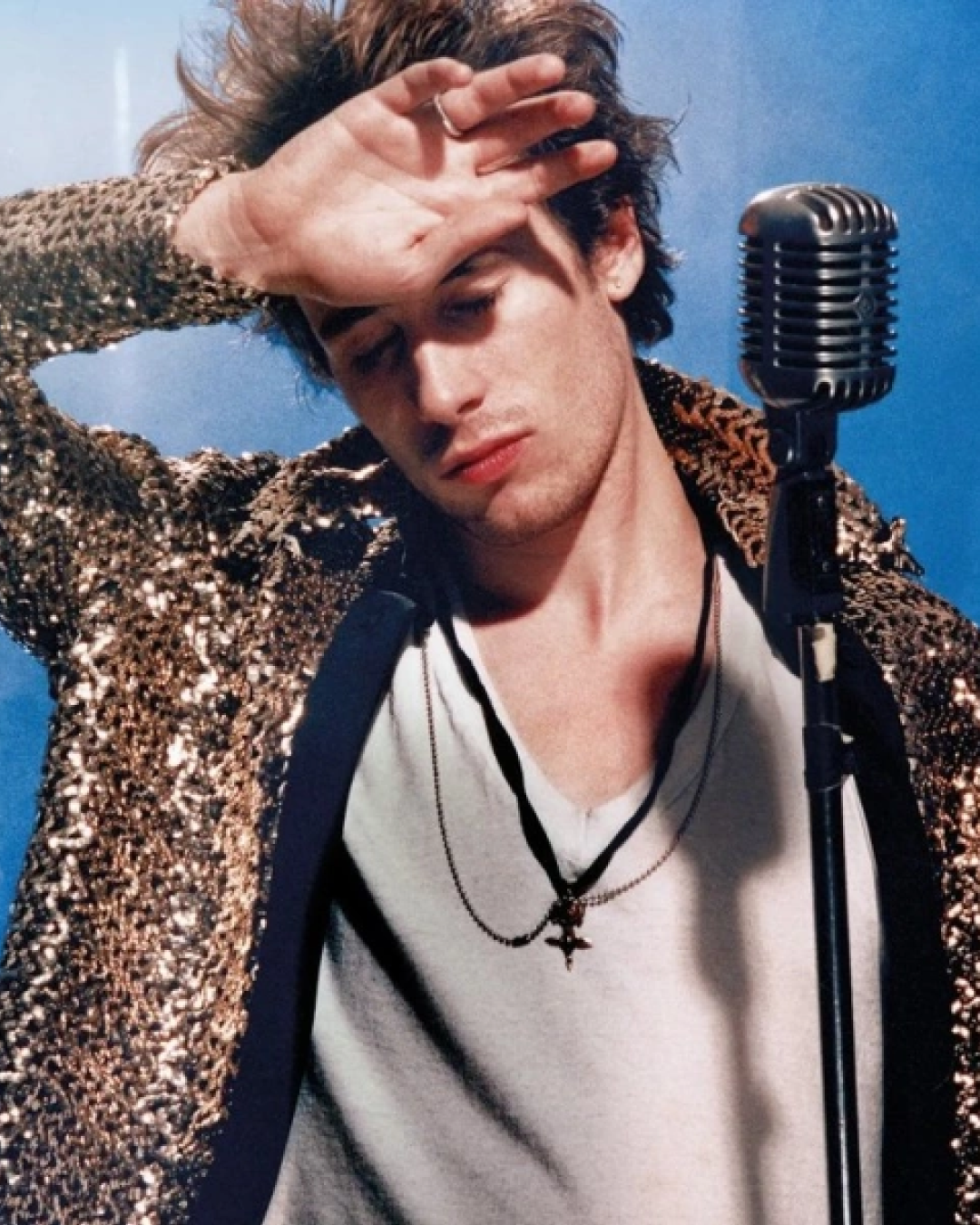

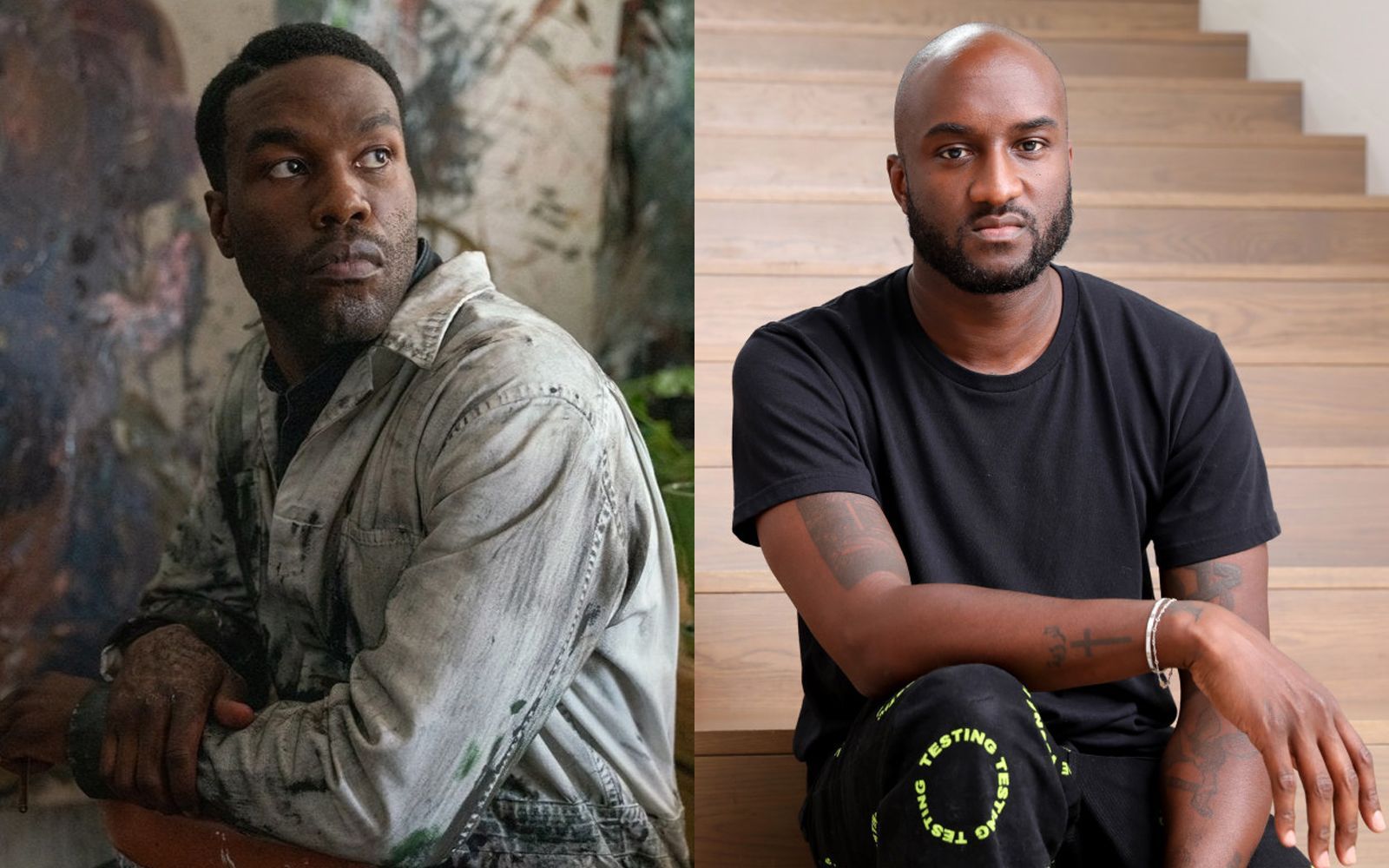

This scene offers a fairly clear answer to those questions, just as - more generally - some of the things that have happened in these days between cinema, fashion and art respond in a certain sense to these questions. Starting from the story of the protagonist of the new "Candyman", produced by Jordan Peele and directed by Nia DaCosta, who takes "spiritual inspiration" from the black horror masterpiece of 1992: Anthony McCoy is a young - not so young - black artist, one of what was called "the promise of Chicago black art", who recently moved to the redeveloped Cabrini-Green neighborhood with his partner, who works like him in art and pays the rent for both of them. The film takes off when Anthony, looking for inspiration for a new exhibition, comes across the story of Candyman, a man with a hook instead of his right hand who avenges the wrongs and violence suffered by African Americans.

In this sense, the actualization of Candyman works perfectly: inserted within the modern black horror - the one that originates with "Get Out" and of which "Us", "Lovecraft Country" and "Them" are the best examples - the film identifies horror with the inhumane treatment suffered by all the men who over time have taken the form of Candyman. The character - who in his original version was played by Tony Todd, who returns to the screen for this adaptation - is nothing more than a proxy to show the origin of the violence. The same violence that in the 80s and 90s stormed entire American neighborhoods, which the institutions had deliberately transformed into ghettos, only to notice when by now violence and degradation had taken their place. It is at that moment that the process of revaluation begins which is, often in a too simplistic way, called gentrification: old buildings are demolished and new, modern ones are built at affordable prices. Those prices attract artists who, with their presence, contribute to making the neighborhood more desirable by inexorably increasing its prices. At this point it is the old inhabitants of the neighborhood who pay the price, forced by the increasing rents to leave the neighborhood. This is what happened in Williamsburg, for example, which Jay-Z recounts in "Dumbo". And Jay-Z, like Anthony McCoy, is one of the answers to the first question: What happens when African Americans gentrify a neighborhood?

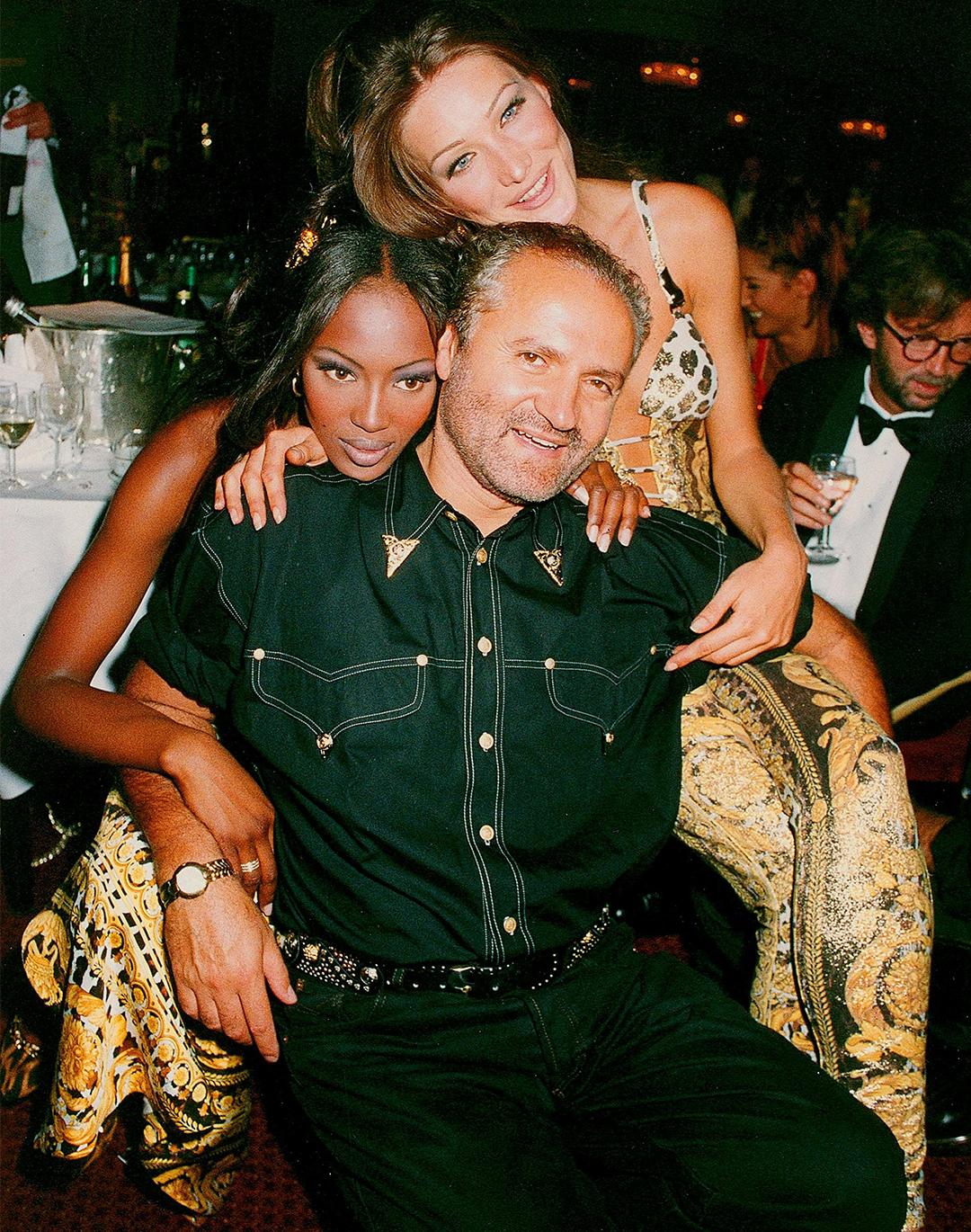

Nia DaCosta, who became the first African American director to break the box office, uses a white art critic to answer this question, in a scene from the film in which, after demolishing McCoy's artwork, he is asked « isn't this what you do? », where that you manages to have a double value, racial and social. But that same question has also been asked several times to Jay-Z, guilty of having contributed to the bourgeoisie of Brooklyn and having become a cog in the capitalist machine - one of the things that was most talked about at the time of the agreement between his Roc Nation and the NFL. Speeches that belong roughly to the same sphere as those that crossed the media (and social media in particular) on the occasion of the latest Tiffany & Co. campaign, which featured Carter's and an almost unedited painting by Basquiat, the black artist which more than any other represented the idea of black art becoming a commodity. Gentrification was intertwined with the idea of exploitation of black art, a concept that goes hand in hand with the idea of "appreciating our art, but hating us" which in a very didactic way can be heard repeated in Candyman.

So what happens when African Americans gentrify a neighborhood? Jay-Z believed he had given a fairly clear answer to the question, in the freestyle dedicated to Nipsey Hussle: «gentrify your own hood before these people do». That phrase was not liked by too many people, from the Washington Post to Taiza Troutman activist and researcher at Georgia State University, who said in an interview: "Black gentrification differs completely from black property, as the latter usually involves black elites who use their wealth and financial capital to secure space and property in the community that are intentionally used in ways that improve the living standards of people already living in the community." Candyman fails to go that deep, trying to raise these issues in a superficial way - in the positive sense of the term - and ending up letting the news, police brutality and the rest swallow up what seemed to be one of the main issues.

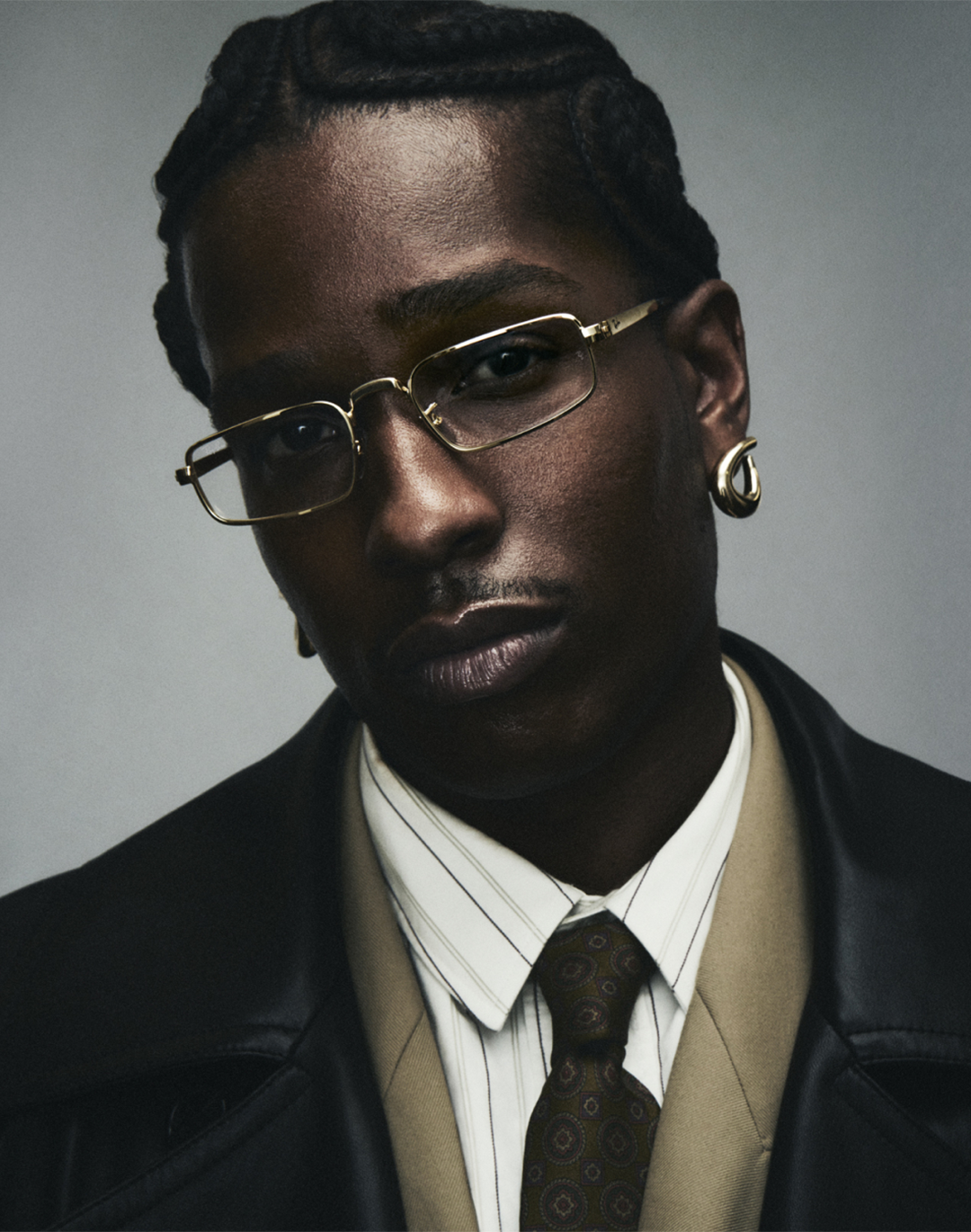

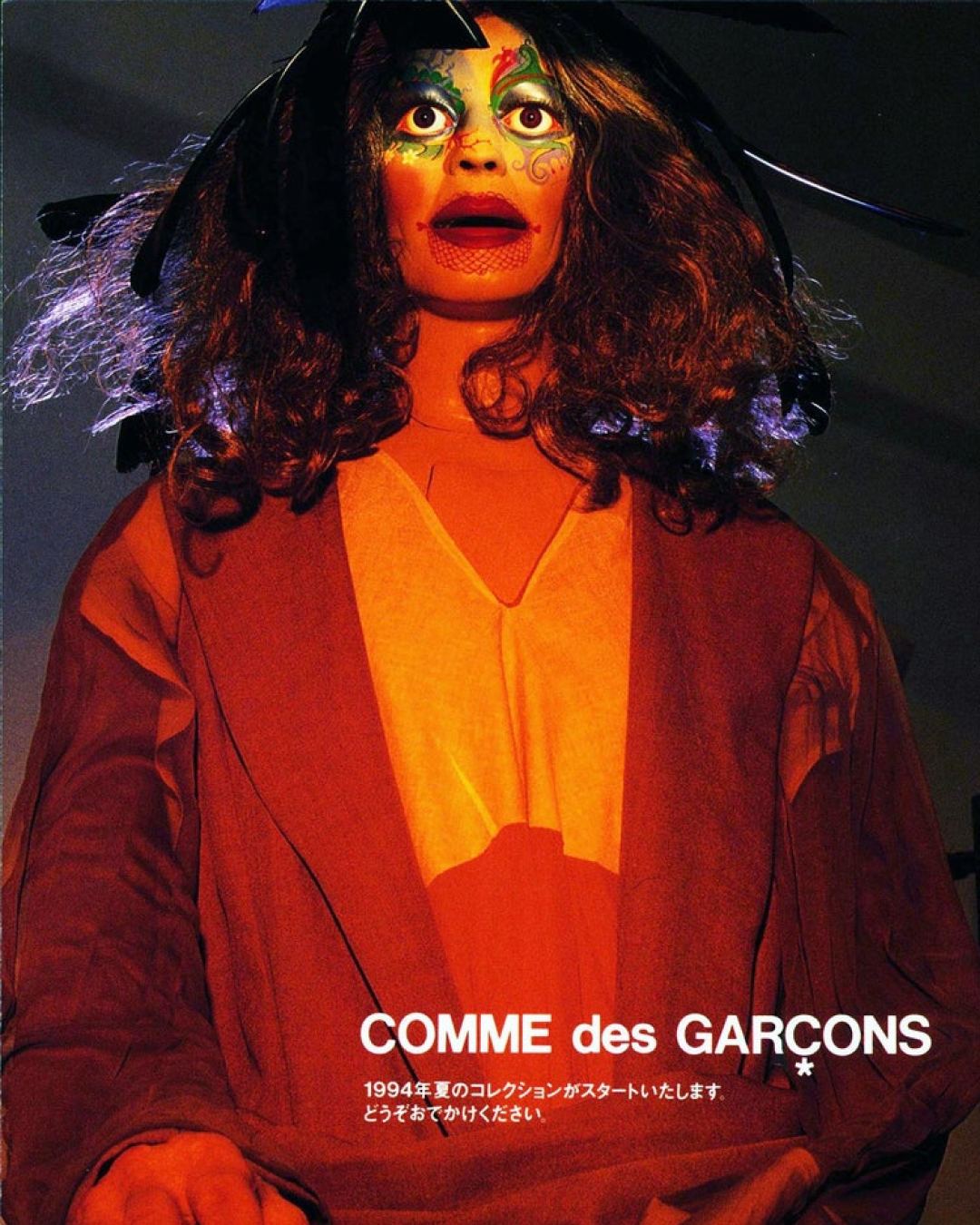

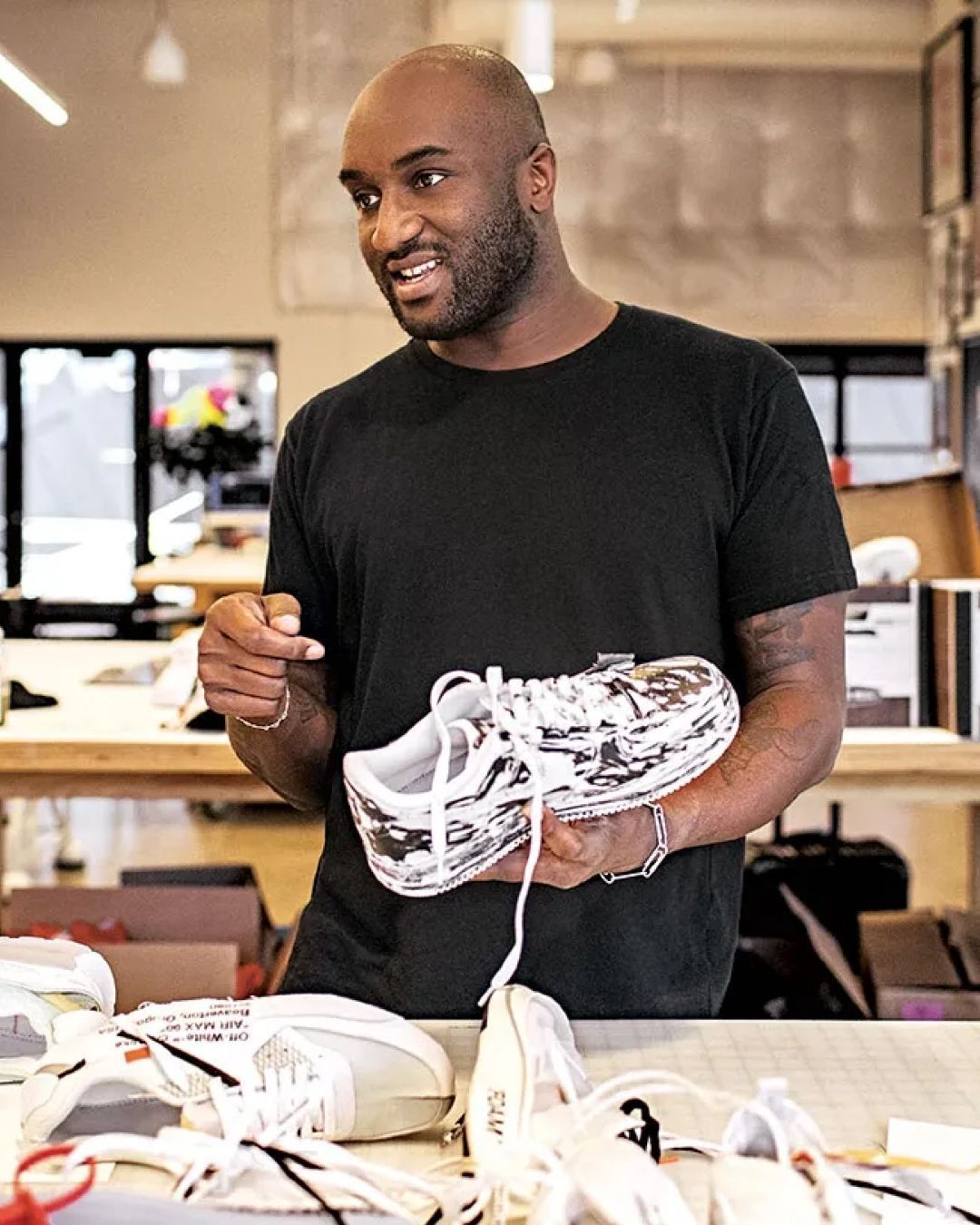

The issue of black ownership had become central following yet another proof of the excessive use of American police force against African Americans: the murder of George Floyd. The media noise - and the incredible boost that the BLM movement has received from it - caused the most immediate social consequence of an endless list of "black owned" activities to be supported. Fashion and streetwear had done the same, putting black owned businesses and black owned brands at the center of attention for an infinitesimally small period. Virgil Abloh himself had created a show, in the very center of white high fashion, Paris, with a dancer wearing a t-shirt with the claim "I support young black businesses".

Abloh, who is constantly referred to as the man who gentrified fashion, had figuratively highlighted how black ownership and "black-lead" were the most important thing. On the other hand, black art has gone through the same dynamics in recent years, only recently managing to enter not only the walls of museums, but in the roles of curatorship and on the boards of the main American art institutes. Was it Brianna who was in the wrong place - trying to exploit black art to benefit her career while her community needed her - or black art itself? And what happens when African Americans gentrify a neighborhood?