What if music were to save Naples from tourism? From the birth of gathering places to a genuine cultural resistance

What is universally recognized as the golden age of the Neapolitan renaissance is, in fact, nothing more than the natural continuation of a season of urban reprogramming that began at the dawn of the first De Magistris administration and, barring any COVID setbacks, has never really experienced a break in continuity. It was ideally sealed with Napoli's third Scudetto, more ideologically than anything else, but it did contribute to an increase of approximately 10% in hotel occupancy, reaching its peak of 80% in 2019 when Capodichino Airport had the highest growth rate in Europe. The fact that Naples is experiencing a boom in tourism is now an established fact, as reported by observers and national news outlets. It feels like we've returned to 2018 when everyone wanted a piece of the Naples brand. However, with this change being a given, the most pressing question immediately becomes: How has this change impacted the social fabric of Naples, especially in reference to the historic city center, which, for obvious reasons, experiences the most significant transformation due to tourism? When we talk about an increase in tourism, our minds often jump to Venice, urban touristification, and the Airbnb-ization of the historic center. These concepts might be called gentrification in other countries and historical eras, but in a context where youth unemployment continues to hover around 50%, they struggle to tell the story of a creative class taking control of the city center. There's also a social aspect that's challenging to convey through statistics: unlike many other major Italian cities, Naples' historic center is densely inhabited, vibrant, and primarily populated by the city's less affluent residents. For some, this in itself guarantees that Naples' center will never lose its essence. For others, it's just another excuse from a people who have the absolute conviction of knowing better than others.

In his book Appugrundrisse, Paolo Mossetti recounts the strange experience of returning to Naples during the COVID pandemic, when it seemed that fate had dealt yet another blow to a city that considers itself unlucky. Instead, it allowed an entire generation of Neapolitans to renovate old abandoned houses and open one of the countless makeshift B&Bs that now form the backbone of the historic center, especially the Spanish Quarters. Naples has changed, and that's undeniable, but from certain perspectives, the city remains the same. It always likes the same things, which may change in the preferences of Neapolitans but ultimately return. One of these enduring favorites is music. It's a common belief that music serves as a necessary palliative for a city that Benedetto Croce once theorized as the "Paradise inhabited by devils." In this sense, one might expect that the best music would emerge from the city during its worst moments, as a means of redemption. In reality, when you analyze the years of the Neapolitan Power and the subsequent New Naples, the city's finest moments have always been intertwined with its musical moments (with some exceptions, of course, like the rise of street rap by Co'Sang). It's because, again, away from the common belief that an artist's work is a reflection of daily life, it's essential to create musical gathering places and groups that allow a movement to collaborate, improve, and mix. The records brought by NATO and Via San Sebastiano in Naples gave birth to the Neapolitan Power, along with a mix of venues in the historic center and the Piedigrotta Festival.

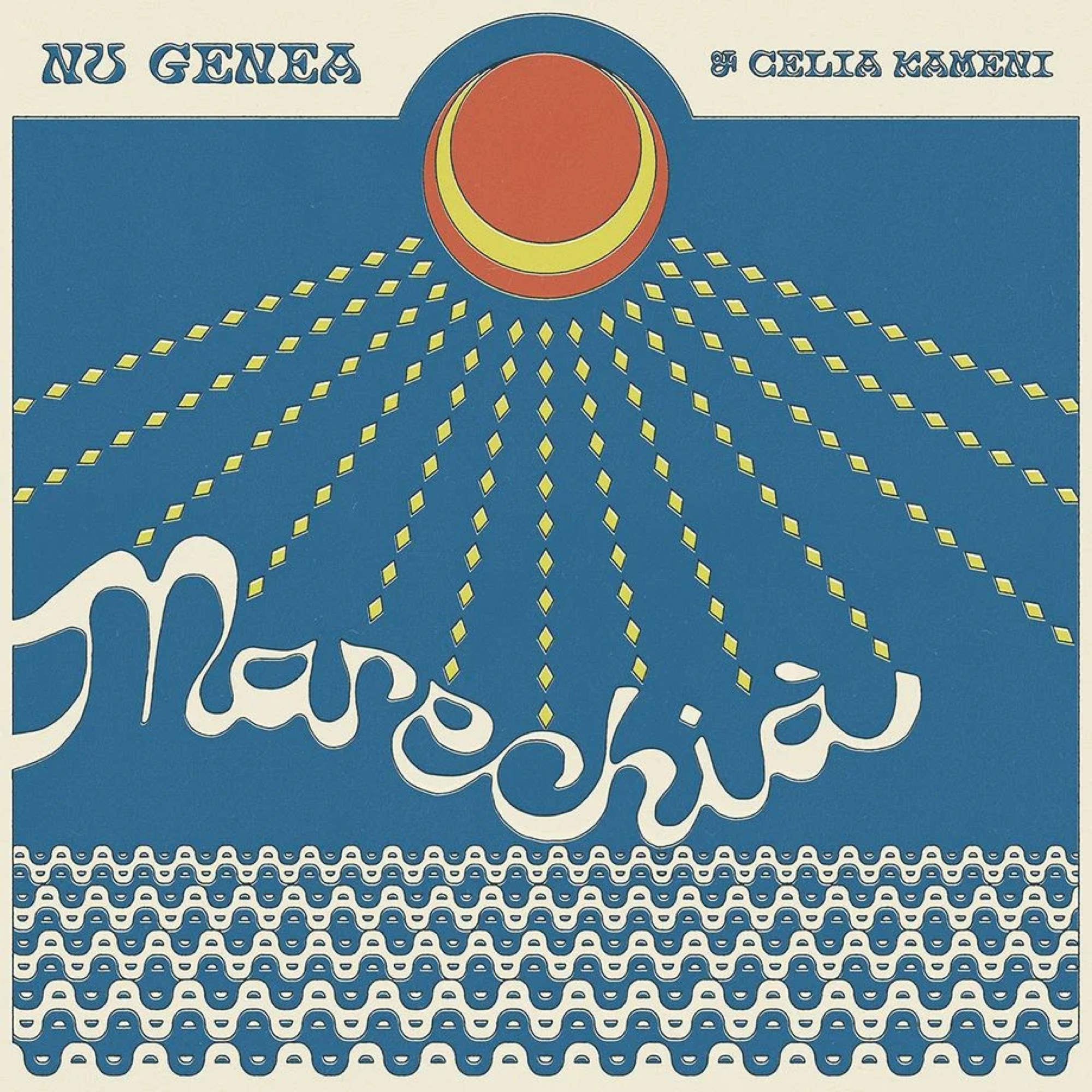

Something similar happened with the Westhill Studios in Camaldoli and Futuribile Records for what was identified as the Newpolitan Sound, the sound of the New Naples that Nu Genea represents but which has an entire class of artists and producers behind it – Mystic Jungle, Whoodamanny, Pellegrino, Periodica Records, or Napoli Segreta – who laid the foundations on which Nu Genea's success rests. It's undoubtedly risky to establish physical gathering places in the era of digitalization and dematerialization of experiences, yet these risks pay off. Like Vesuvius Soul Records, a record store ironically located on the street adjacent to Via Pino Daniele in the heart of Naples' historic center, which has become a place of musical resistance and innovation. Over time, it has also become a "tourist" destination, in the sense of a space in the historic center where one can have authentic experiences, away from the clichés of the new postcard Naples, which comes with its own set of problems. What if this were the solution to prevent cities from losing their vibrant soul as they quickly become low-cost tourism goldmines in the age of Booking? Generating genuine moments of social gathering that go beyond mozzarella, stale sandwiches, and stories about a city where an increase in tourists is accompanied by an increase in problems. What if music were the act of cultural resistance that helps Naples preserve its soul?

We'll be discussing music, physical gathering spaces, and tourism during the talks at TUM, in Quartiere Intelligente, Naples, on October 21st. You can register here.