The ultimate redemption of the corset From Maison Margiela's show to the Sanremo stage

Last year, during Sanremo Festival, we commented on the rising trend of men's corsets, first seen on the fashion week runways, and then brought to the Ariston stage by Blanco. In that article, we noted how the surge of corsets seen between the FW23 and SS24 seasons actually had a historical basis, being the classic bodice widely used by those English dandies who first conceived the idea of a public figure linked to a specific personal style and provocative attitude. However, a year has passed, and discussing the legitimacy of fluid dressing still means touching on a topic that has already been examined far and wide, becoming somewhat tiresome: genderless or fluid fashion is now considered normal, either completely accepted or silently left behind. Corsets have continued to appear at the margins of the collective imagination, albeit infrequently but in significant moments: the incredible show with which Maison Margiela closed Couture Week; Mahmood's look on the Green Carpet the night before the start of the Sanremo Festival, which came from that collection; BigMama's evening gown, also at the Festival, designed by Lorenzo Seghezzi; the looks worn during the award season by Taylor Swift, Selena Gomez, Halle Bailey, Nicola Peltz, Blue Ivy Carter, but also Kylie Jenner, Billie Eilish, Jennifer Lopez, Victoria Monet, Doja Cat. In all these different cases, we can certainly identify a trend in evening or ceremonial wear that includes laced bodices, but we also notice something else: the semantics of the corset have completely changed, shifting it from an antiquated symbol of oppression to a vehicle for rethinking gender binarism, as well as an increasingly emancipated expressive tool freed from its ties to eroticism.

Mahmood sul green carpet#sanremo @Mahmood_Music pic.twitter.com/dQ4Jkm5Tjo

— Clara (@MariaclaraPra1) February 5, 2024

A couple of years ago, a film presented at Cannes that recounted episodes from the life of the famous Princess Sissi was called Corsage – a title that made the corset or bodice of the protagonist's royal dresses, obsessively tight in an attempt to control one's figure, breath, and limits of resistance, the metaphor for an atmosphere where women's oppression was not only external, but oftentimes internalised. Essentially, since their existence, corsets have been seen as symbols of vanity and abuse, both of oneself and of gender: philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau lamented them as early as the late 1700s in the pages of the Lancet, starting around 1860 the moral panic against corsets was in all newspapers despite being considered an essential requirement of the female wardrobe by society as a whole, and it was the very first feminists who made them a symbol of oppression – so much so that Dior's famous Bar Jacket, in '47, which featured a wasp waist in which a woman could not move or work, was seen as a very reactionary design at first but still became a global success, and it cannot be forgotten how Chanel is credited with liberating the female wardrobe from corsets when it is true that much of Belle Epoque fashion had already begun to do without them. In a somewhat banal manner, what attracted to the corset was its ability to "create" the impression of thinness and define a silhouette - in an era where the idea of training to sculpt one's physical forms (forms that were rarely seen live in public) was something vaguely foreign. When the corset became the subject of debate, the division became cultural: those who wore them defended their use, claimed to find pleasure in wearing them and in the discipline necessary to hold them and accused their detractors of never really wearing them; those who opposed them called them a symbol of oppression. In the end, partly for convenience, partly for historical necessity, and partly because they were still the prerogative of a declining aristocracy, their use was gradually abandoned as the female wardrobe became more practical and "bourgeois".

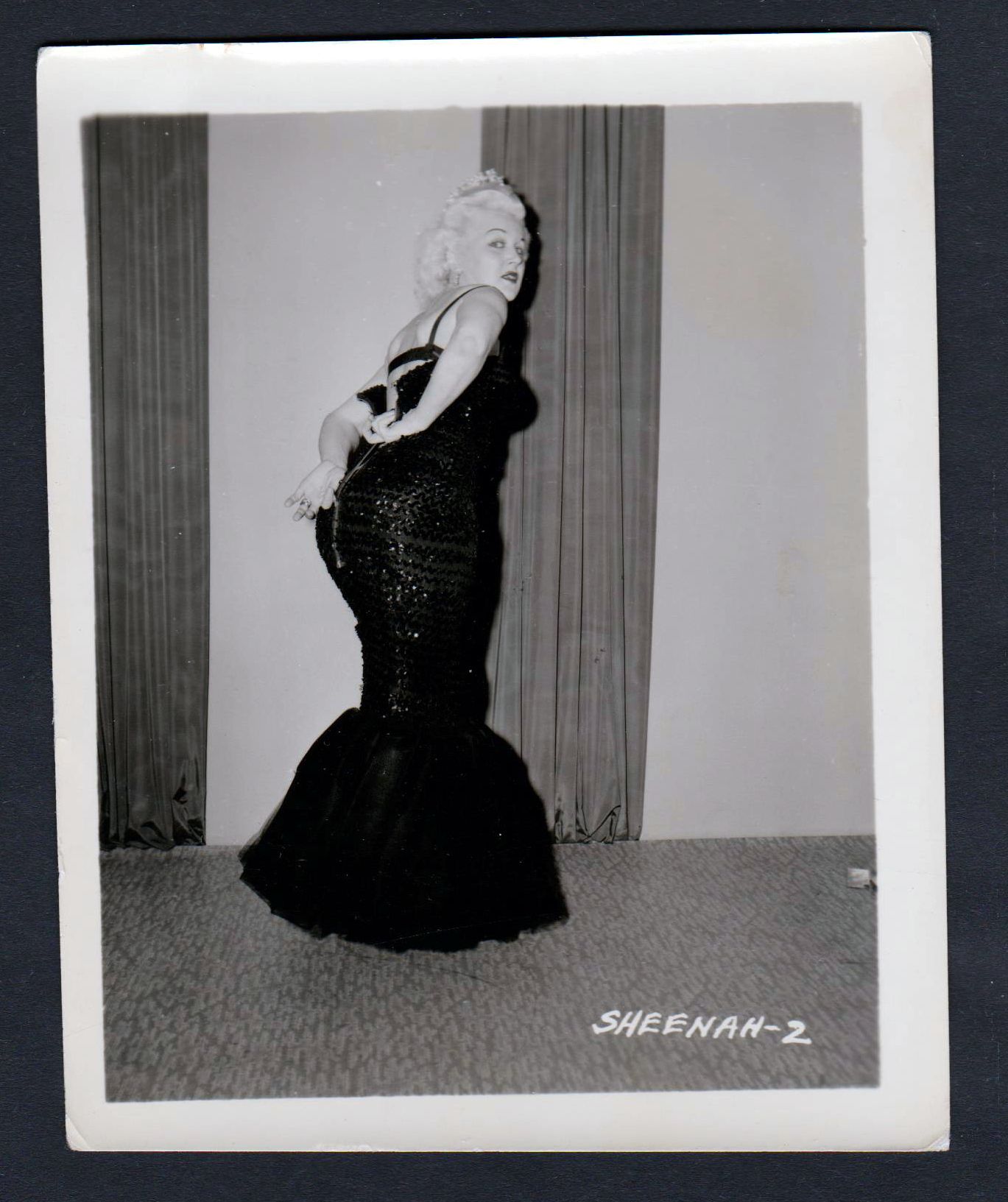

Meanwhile, corsets, along with all women's lingerie, given their ability to create unnatural and exaggerated silhouettes, penetrated the realm of erotic fantasies of Sacher-Masoch, into proto-pornography born with early 1900s cameras, in the disturbing photos with which self-proclaimed "Pin-Up King" Irving Klaw stirred the imagination of 1950s America. In the '70s Vivienne Westwood brought them back during the SEX store times and then again in the '80s (the one presented in 1987 remains famous, making it a cornerstone of the brand's language) when, in France, both Gaultier and Mugler popularised them: intimate attire became just clothing, sex could be displayed to dominate with audacity an increasingly declining respectability which was never truly banished. The corset was not normalised, only sexualised in a more socially acceptable way: it still remained a kind of costume, romantic in its antiquated nature, beautiful because evocative of some forbidden dimension - a fetish, in every way. A few years later, for his SS95, Alexander McQueen brought the famous Mr. Pearl on the runway more to shock than to question gender norms, and twenty years later, when Miuccia Prada gave them a central role in the FW16 of her brand, they were more exotic than erotic – they were not, however, normality, they were not just another piece of clothing but an eccentric element, which served to reflect on looks and which took up the theme of a collection concerning women's wear archetypes and their general conceptual rethinking.

@zozoroe Reply to @zozoroe Uhm... OMG I’M NEVER TAKING THIS CORSET OFF #fyp #corsetchallenge #corset #YasClean #viral #tryonhaul #aprilfools Lacrimosa - Vienna Mozart Orchestra

After 2020, with the media explosion of Bridgerton and the proliferation of aesthetics inspired by every possible pre-existing imagery, it was the moment of Regencycore and the resurgence of corsets - and here, without a doubt, the work of Dilara Fındıkoğlu should be mentioned. With this trend, moving from the scenic reality to the everyday one, the corset has become almost a romantic accessory designed, more than to constrain and contain, to define and shape without compression, to create a silhouette and evoke a kind of modern fantasy on par with military-inspired jackets or slightly '70s bootcut jeans. The corset has briefly moved from a mischievous symbol of forbidden dimensions to a more pure expressive vehicle: this is how John Galliano used it for the already famous Margiela show (even though corsets had appeared in the brand's collections for three seasons, and Galliano has been using them for decades) where the corset was indeed a historical evocation but also an artistic tool that surrealistically deformed the models' silhouettes and a layering element.

Mahmood was the first celebrity to wear a look from that collection after the fashion show, giving his outfit a queer dimension but with almost nothing explicitly or exclusively sexual; just like BigMama's outfits in the first two evenings of the festival, designed by Lorenzo Seghezzi, who made the corset the pivot of an entire visual language that in its ambitions goes far beyond the banality of erotic suggestion to broaden the discourse to the concept of queerness itself and the eradication of traditional clothing binarism. The cultural moment seems ripe, in any case, for this resemantization: on TikTok the #corsetchallenge reached 690 million views just in January, according to Vogue, and involves an audience of all genders and body types - demonstrating that, if nothing else, what in the 19th century was a social requirement expected of women has turned into something to play with and do what we prefer to do with clothes: have fun.