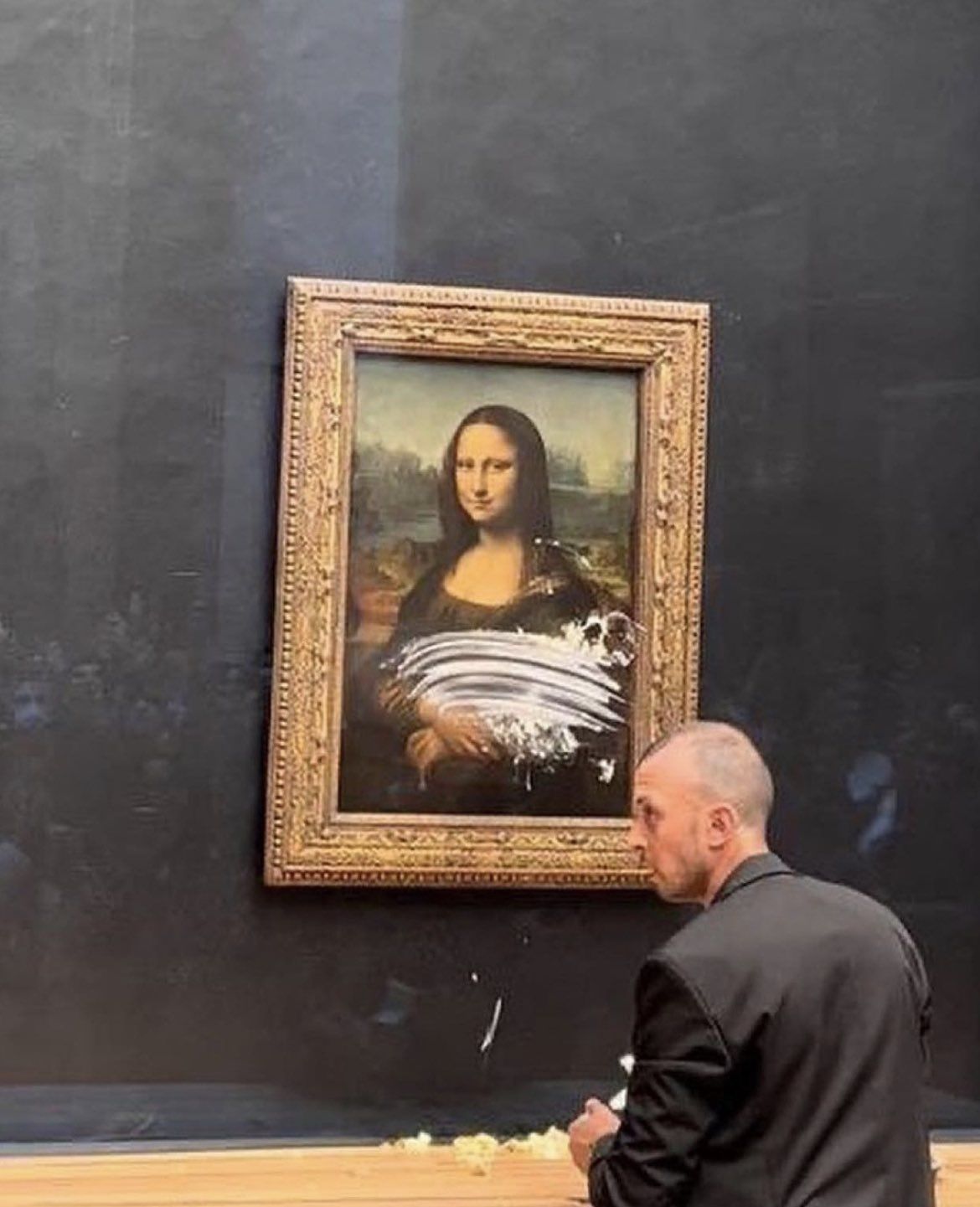

Can vandalizing the Mona Lisa be an art performance? Reflecting upon the "cake vandal" incident.

At the Louvre yesterday, a man whose name has not yet been revealed tried to vandalize Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa by throwing a cake at the painting. After throwing the cake, which obviously smashed against the bulletproof glass case protecting the painting, the man threw roses around himself before being dragged away by museum guards shouting phrases that a Twitter user transcribed: «Think about the Earth, think about the Earth, there are people who are destroying the Earth, think about it. All the artists tell you think about the Earth, all artists think about the Earth, that's why I did this, Think about the Planet». The affair certainly has grotesque overtones, considering the fact that the activist had dressed up as an elderly disabled lady and had a wig on, to the somewhat comical throws of cakes and rose petals - none the less, the lucidity of the gesture, its premeditation, and above all the clear awareness on the part of the vandal/activist that he could not actually damage the painting make the whole episode seem like a kind of performative gesture. The man must have known that the Mona Lisa would not be damaged, that his gesture would probably be useless - and this is because the real motive of his gesture was to send a message, not unlike that activist who interrupted the Louis Vuitton show last October.

Maybe this is just nuts to me but an man dressed as an old lady jumps out of a wheel chair and attempted to smash the bullet proof glass of the Mona Lisa. Then proceeds to smear cake on the glass, and throws roses everywhere all before being tackled by security. ??? pic.twitter.com/OFXdx9eWcM

— Lukeee (@lukeXC2002) May 29, 2022

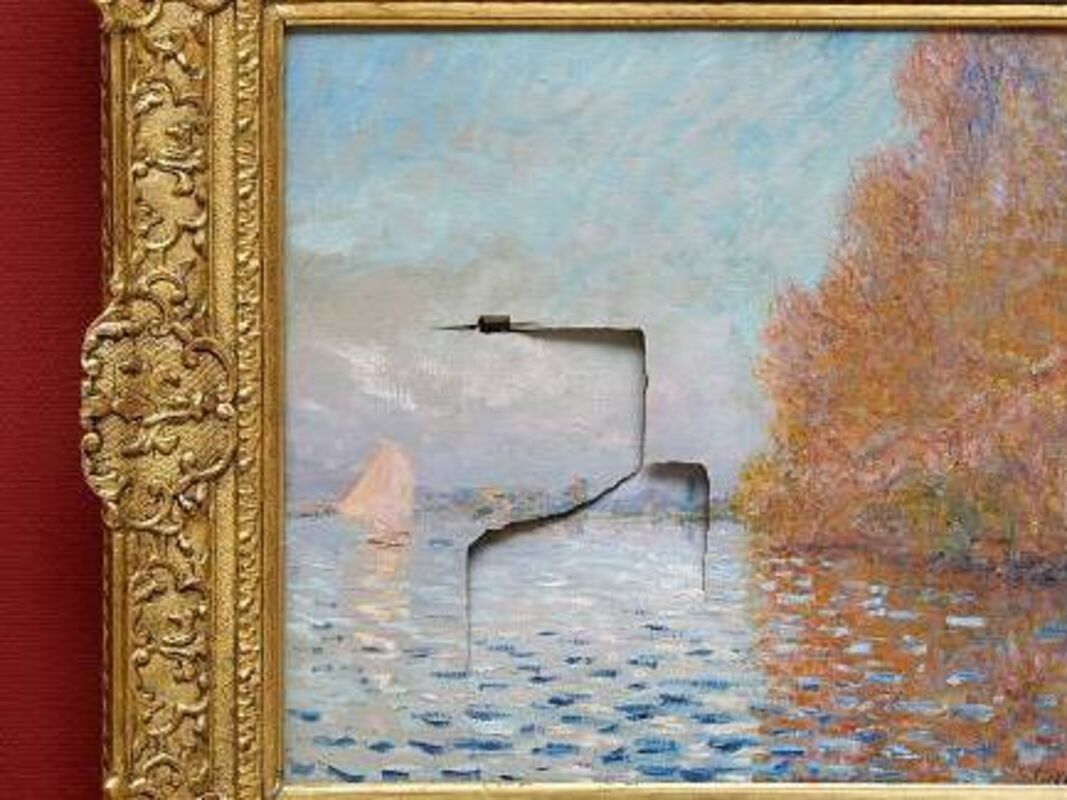

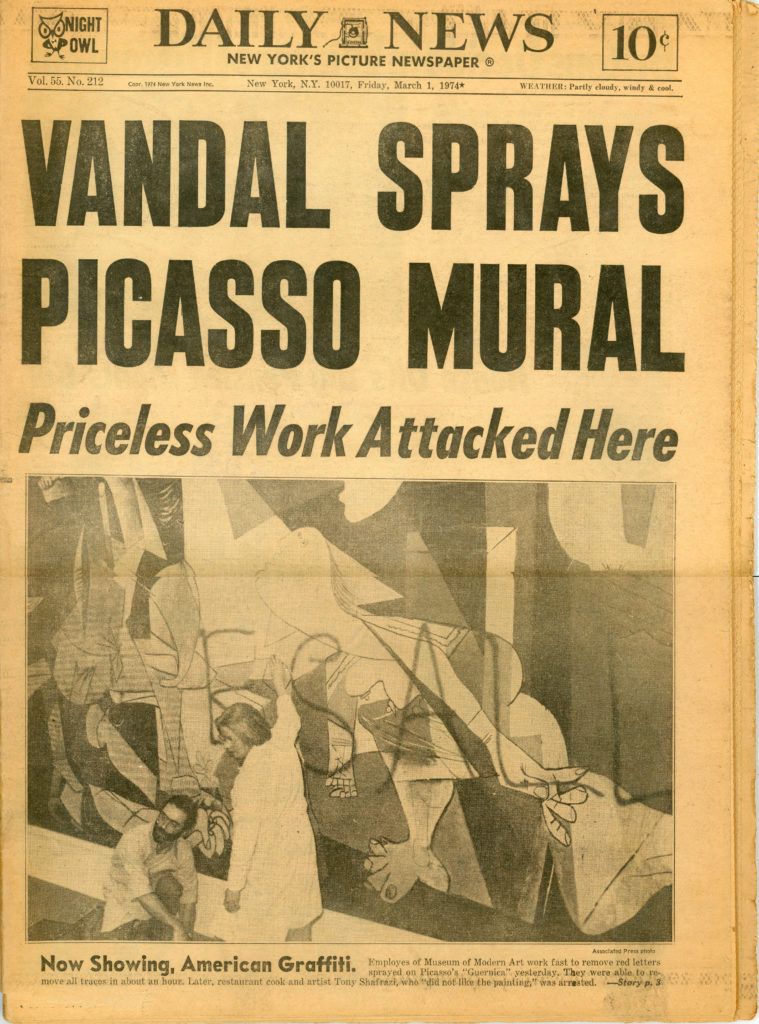

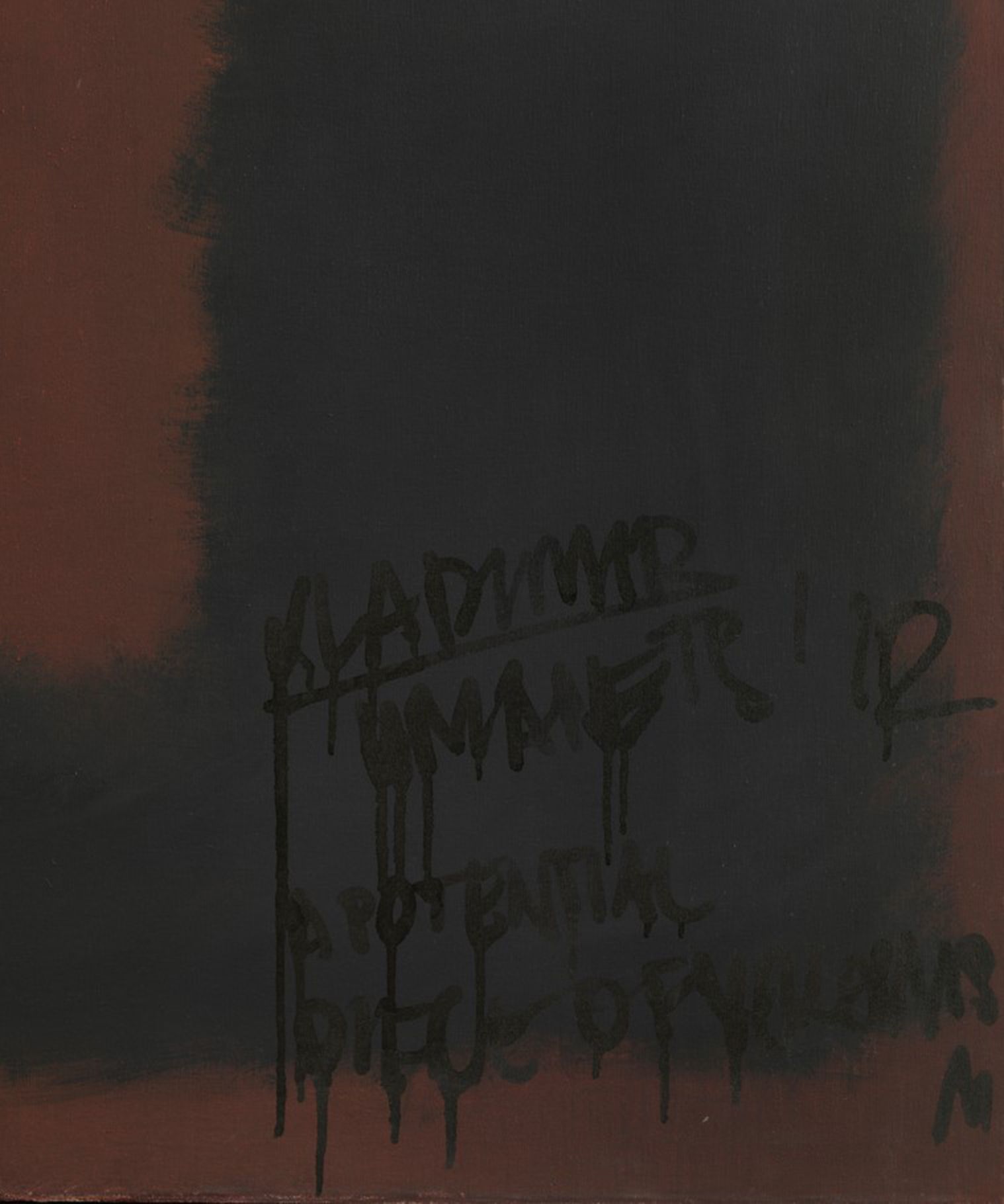

Among the world's most famous works of art, this is not the only time the Mona Lisa has become the victim of vandals. In August 2009, a Russian woman who had not received French citizenship threw a porcelain cup at the painting, which, that time too, shattered against the bulletproof glass protecting it. Then in April 1974, while Leonardo's painting was at the Tokyo National Museum, a woman sprayed red paint against it to protest the museum's lack of access for the disabled, while in 1956, while the work was on display in Montauban, two different vandals had damaged it by throwing a rock and acid at it, respectively. Just as happened with countless other masterpieces of art, from Michelangelo's Pieta to Picasso's Guernica, acts of vandalism are often due to the actions of mentally challenged individuals (after damaging the Pieta in 1974, Laszlo Toth proclaimed himself as the new incarnation of Christ) or, in most cases, to acts of protest. In 1914, suffragette Mary Richardson cut up Velazquez's Venus in London to protest in favor of face rights for women; in 1970 Rodin's The Thinker was blown up in Cleveland by members of the terrorist group Weather Underground in protest of the American presence in Vietnam. Another more cross-cutting category includes vandals/artists who turn vandalism itself into performance: the man who in '74 wrote Kill Lies All on Picasso's Guernica with spray paint shouted «Call the curator, I am an artist»; while in 2014 Wlodzimierz Umaniec wrote with a black marker on a Rothko painting, signing himself with an artistic pseudonym.

Without, however, wanting to justify the gesture of the "cake vandal," in itself also quite harmless, it is very striking how activists and artists decide, if not rationally, at least lucidly to vandalize great works of art as a form of revenge on institutions. An attitude exemplified by the words of Andrew Shannon, who in 2012 punched a Monet painting in Ireland to «get back at the state». As mentioned above, the throwing of roses and the message shouted to bystanders make yesterday's episode a kind of performance art - a quite shocking performance for a public accustomed to the kind of tame, inoffensive, marketable art such as that targeted by the vandal. Specifically, the Mona Lisa has over the years become a symbol of the state, its institutions and its reassuringly quietly museified art - it is against this state that the man has thrown his cake, or against this status quo, of which the Mona Lisa is only merely an embodiment.

The gesture inevitably makes one reflect on how, after all, a large part of our contemporary art is not so much about creating icons for the future but about our relationship with the icons of our past. Every work of art that reimagines an iconic pop culture character, from Andy Warhol's Marilyn Monroe to Daniel Arsham's Pokémon, represents this kind of attitude - yet from pop art onward the general public's taste has by far favored tame, neo-bourgeois art over a far more radical, iconoclastic, and subversive kind of performance art, of which the case of the "cake vandal" is perhaps an unintentional and tragicomic example. And in a world in which art, and especially its new frontier of NFTs is increasingly reduced to a vehicle for socio-political messages or a mere asset to be sold and traded, a "product" like any other that must be solvent before it is meaningful, it would perhaps serve to return with our thoughts to a time when art did not console us, indeed, a time when the world of creativity still had the capacity to lash the public consciousness with the brutal sincerity of its subversive gestures.