Why does China cancel brands? Sometimes an apology is not enough

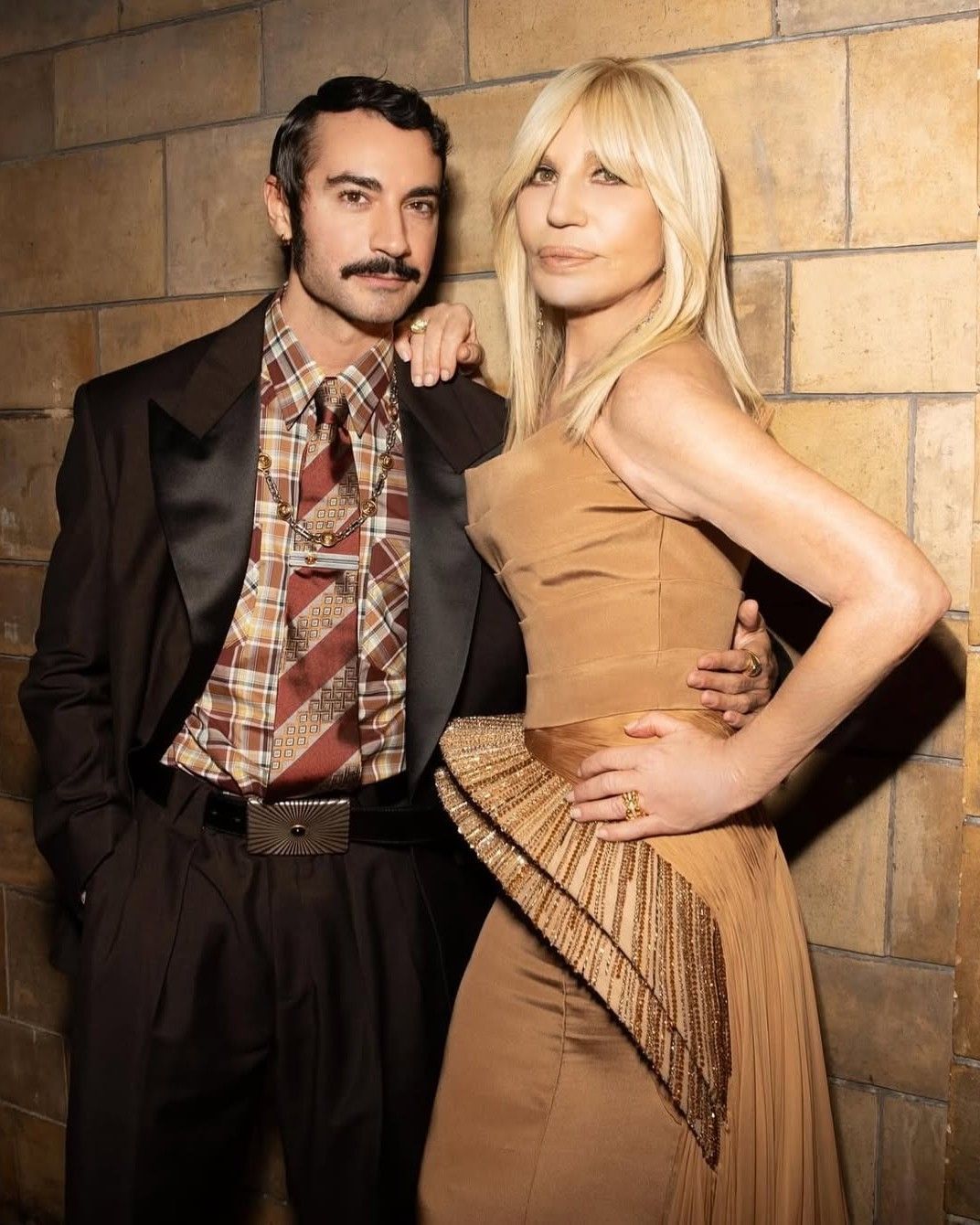

According to a study conducted by BOF, growing nationalism in China continues to be a threat to foreign brands, which have experienced at least 78 boycotts since 2016, a number six times higher than in the previous eight years. China's 1.4 billion buyers represent an incredible revenue potential for international brands, but at the same time the strict political regime has always been an obstacle, especially during historical periods of particular tension such as the trade war between China and the United States or the demographic and cultural genocide of the Uyghurs, a crime against humanity that brands have publicly condemned, soon suffering the consequences. Generally speaking, US, Japanese and French companies have been the most frequently targeted, in sectors such as food, beverages, luxury goods and the automotive industry. State media, for example, supported a 2019 campaign against luxury brands, including Coach, Versace and Givenchy, for not respecting 'China's territorial integrity'.

It is very easy to hurt the sensitivities of the Chinese government: Walmart Inc. had to apologise in 2018 for a sign in one of its Chinese shops indicating Taiwan, not China, as the origin of some products, but did not do so in 2021 following accusations on social media that it had taken products from Xinjiang off its shelves. However, it is difficult to discern whether or not it is better to justify oneself in the face of accusations, in the case of H&M - the largest company targeted by the wave of boycotts linked to Xinjiang last year - not apologising, stating that it has always respected Chinese consumers and is committed to long-term growth in the country, led to deletion from almost all e-commerce platforms, in other cases, however, the apology caused a further backlash, with social media users accusing companies such as Hugo Boss of behaving hypocritically.

Xi Jinping ha visitato lo #Xinjiang. Intanto tarda ad arrivare il Rapporto @UNHumanRights della visita del Commissario ONU per i Diritti Umani @mbachelet effettuata a maggio nella regione abitata dagli #uigurihttps://t.co/WQYCfewyPO

— Matteo Angioli (@Matteo_Angioli) July 15, 2022

A winning strategy has been that of Uniqlo, which, despite the historical rivalry between China and Japan, has quickly managed to become one of the favourite clothing brands in China. So although anti-Japanese sentiment in the country is pervasive and competition with local brands increasingly fierce, the Yamaguchi-based brand, known for functional staples such as T-shirts, jeans and thermal underwear, has secured 1.4% of China's $350 billion clothing market by 2021, according to Bloomberg: a larger share than any other brand, up from 0.4% a decade ago. Moreover, between 2018 and 2022 - a tumultuous period that saw some global brands hit by nationalist boycotts in China - Uniqlo remained among the top five womenswear retailers on the e-commerce platform Tmall, the only foreign brand not to lose its position by choosing to keep well clear of any political conversation. Surely the key to success and collaboration with the Chinese government is silence, but is refusing to publicly take sides in the face of, say, a genocide such as the Uighur genocide in honour of sales really forgivable?