Is the return of the perfect bodies of the 2000s good news? From Olivia Rodrigo to Dua Lipa, the real step forward of the Y2K revival

The hashtag #throwback2000s but also the profile @thr0wback2000s on IG give a very clear idea of the fact that we have suddenly fallen back into a spiral of skinny pants, Destiny's Child, spring breakers teen pop, Britney Spears, soft colors, sex and thin bodies. Something that until yesterday was remembered as horribly decadent, millions of years away from the new idea of inclusion and body positivity, something that we thought we had left behind with the closing that we believed to be definitive of Sex and The City and that instead, just like in every respectful horror, comes to life at the end leaving us foreshadowing sequels full of destruction and rolling heads.

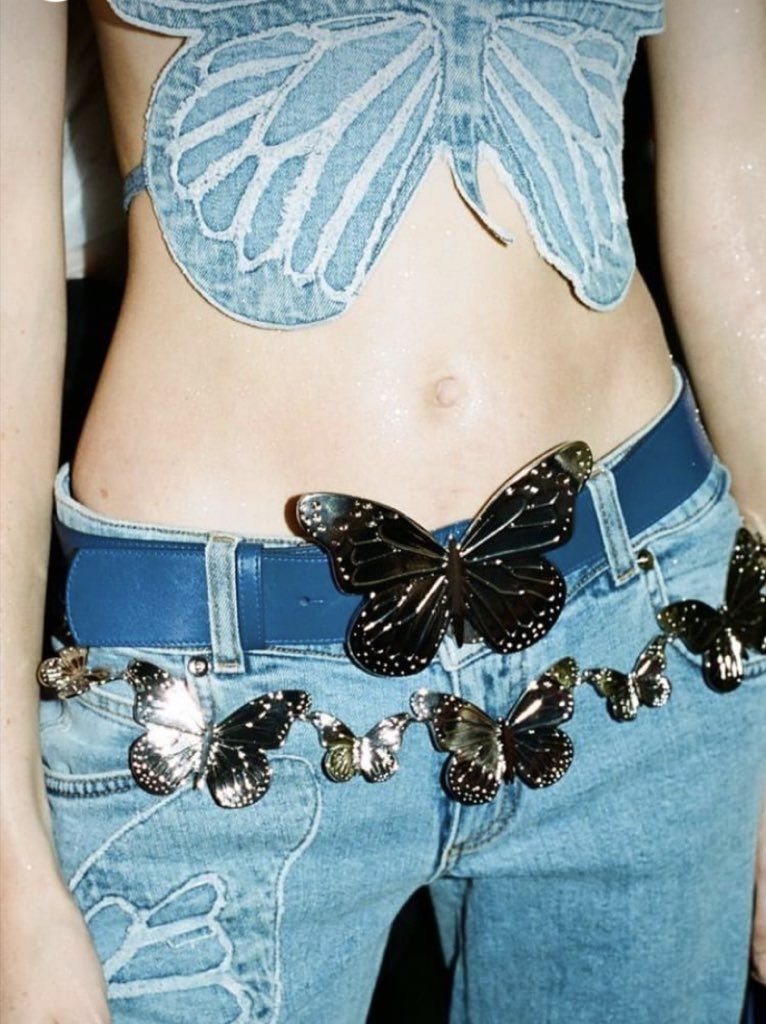

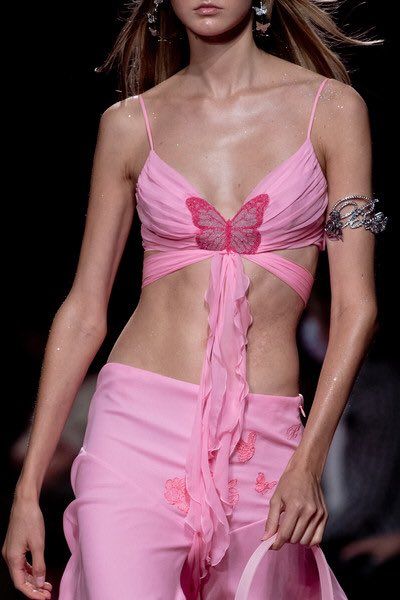

Y2K, an English abbreviation of 2000s born from the name of a computer bug that never really existed, is the term suddenly on everyone's lips after the seminal MiuMiu fashion show for SS22 or that of Blumarine by Nicola Brognano and Lotta Volkova, which combines an air of restless light-heartedness with an apparent involution in customs, with a hasty forgetfulness of the achievements hitherto made not only by political activism but also by common aesthetics. If you don't have the faintest idea of what I'm saying, go and see Spring Breakers, 2012 masterpiece by cult director Harmony Korine (you can find it both on Prime Video and Apple +), in which a trio of, as Cristina d'Avena would say , "Three beautiful girls / they are three very skilled thieves / very smart, very agile / with cunning and skill / and always combining a little cunning / always manage to escape / and disappear in nothing". The three girls in question, sixteen-year-old psychopaths addicted to drugs and occasional sex, manage to gain the upper hand over a gang of robbers and drug dealers in a world made of sequined bikinis and guns, of pop Miami style colors and psychoactive substances. You will hardly be able to find something more politically incorrect and, in fact, far from what has now become the true religion of inclusion.

Indeed, the point is probably just that. After years of media and aesthetic pressure on issues such as gender equality, neo feminism, non-binarism, fluidity and body positivity (if any of these terms are foreign to you it is because you have lived on another planet in recent years), what we are seeing happening in front of our astonished eyes is a redirection towards the polarization of genders and roles, an incredible nostalgia towards lightness, superficiality and unconsciousness (even chemically induced) and a mad desire for perfectly thin bodies, sexualized, admired and objectified. As if behind the flag for the empowerment of Dua Lipa, Ariana Grande, Selena Gomez and Olivia Rodrigo, the putative daughter of Britney Spears, there was not only a fierce claim of the right to re-appropriation of the female body but also a true and serene desire to have fun without any political or social excuses. Fortunately, nothing is ever as it seems in fashion (as well as in life) and if you go to see the video of Brutal, the first single of the album Sour, directed by the cool Petra Collins, our Olivia Rodrigo is certainly dressed as a former Disney girl while she sings Oops, I did it again but the lyrics say things like “I feel like nobody wants me / I hate the way I am perceived / I only have two true friends / and lately I'm in a depressive crisis / because I fall in love with people who I don't like / hate all the songs I write / I don't feel beautiful or smart / and I can't even double-park". For a debut album that has managed to beat even the unshakeable Taylor Swift in sales, this isn't exactly a reassuring message.

The reality is that the 2000s of Olivia Rodrigo and most likely of all Gen Z are not a period to return to forget today but the representation of a moment of planetary alignment in which it seemed that collective happiness was gushing free from the public fountains and that the ecstasy tablets could be dissolved in water instead of an Alka Seltzer, without particular negative consequences for anyone. So also fashion is returning to be interested in that moment, because, being a complex system of production of meaning, it needs to go back to looking at what it was before the inclusion revolution, when it prompted the world to reflect on the meaning of bodies that are too thin or too fat, which has subverted the categories of masculine and feminine forever.

What is happening is not historical revisionism but a profound analysis of a decade that we all looked at with sympathy and sufficiency, which was instead the driving force for everything that came after, for a radical awareness of the fundamental values of that decade (success, fame, perfection, sex and optimism), that if they had not existed they would not have been dismantled and would never have led, by reaction, to the conquests we have made. Going back to seeing thin bodies on the catwalks is good and right both because it is part of a complete inclusion process and because it reminds us of the starting point of a positive evolutionary process that we hope is only just at its beginning. One of the most powerful forms of fashion storytelling is the ability to reread, through aesthetics, very recent social phenomena that had not yet been given a precise historical value. The lean bodies we've seen come back in the spotlight aren't a step backwards. They are there to remind us of when diversity and differences were not only not considered values but were not even part of the discussion. They were unthinkable.