The Matchday's programs long tradition

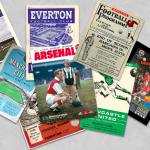

Printed since the 1880s, soccer club newspapers were and are a link between fan and club. But with digitization, a lot of memories will be lost.

February 11th, 2022

For a long time now, in the publishing industry, but not only there has been talk of the effects that the digitalization of information is having. A process that, in the different levels of publication, also involves independent publishing up to that of soccer teams. It is no longer the custom, in stadiums, to go through the gates and stop for a few seconds to pick up and browse through the various matchday programs left there by the home club.

In some cases they are a pamphlet, in others one or two Berliner or A3 sized sheets, in others still a real magazine, like the one published every month by Sudtirol FC, a Serie C club, a magazine of almost 50 pages with news, interviews and special features. The aesthetics of these small magazines is all aimed at the fan, so, as in a normal magazine - music, fashion, soccer - on the cover a character is exalted: the coach, the most prolific striker, the captain, the latest purchase. And just like a newspaper it has a colophon with editors, graphic designers and administrative managers, a director who coordinates and often an editor. There are sponsors, as is the norm, and all the companies on the advertising boards at the edge of the field are in it. There is also a photo section - Sportweek style -, a comments section, and a chronicle of the main events of the moment. Equally unfailing is the page dedicated to the opponent of the match.

In the older magazines, there are the Nineties layouts with the cover framed by cubist lines, and others that are a bit more VHS version with bombed out fonts. In the most recent ones, from the mid-teens of the 2000s, you can see several players superimposed, often with close-ups and their faces in overlay. The centrality of the player is the fundamental aspect, as if they were Hollywood actors. In this we see again the editorial principle of exalting a character, of choosing a star and putting him in the limelight.

This whole world is now suffering from digitization. There are several cases even in Serie A, Milan (only digital), but also Inter (edited by the Inter media house), Napoli (Napoli stadium, physical) Roma (very up-to-date, but online), while others have a real magazine that can be bought directly at the newsstand, like Lazio with Lazio Style or Udinese with L'Udinese. Many other European clubs now publish their match programs directly on the app or as a pdf on the website. Aesthetics and, above all, memories suffer from this phenomenon.

In a piece in The Guardian, Elis James reflects on the end of match programs and on how difficult it is to do without these magazines, especially for emotional reasons. This is a theme dear to the sports editorial staff of The Guardian, having already spoken about it when the English football league voted to abolish the obligation to print football programs (according to some clubs, their earnings were not equal to their production costs), writing about how those little pages at the stadium entrance were mainly there to create a bond between fans and clubs.

They are heirlooms, Proustian madeleines of old sporting achievements or disappointments that have the same value as a photograph. On the other hand, they have a very ancient history, dating back to the first professional clubs. The first match program, known as The Villa news and records, was printed for the match of September 1, 1906 between Aston Villa and West Midlands, but there are those who say that the real, first issue was the one of 1873 referring to the college match in Connecticut between Eton and Yale - found inside a book, it was sold for 30 thousand pounds. They are in fact objects of fundamental importance to remember soccer and, needless to say, it's an English fetish: in the National Football Museum in Manchester there is a section entirely dedicated to football match programmes.

But it's not just memorabilia. There's also a lot of coolness. Especially in England, as with anything involving a rolling ball, there are thousands of online aficionados looking for old copies of match programmes. On the footballprogrammes marketplace (what other name could there be?) you can find everything from England-West Germany in the 1966 World Cup to a charity match between Gerrard's Best XI and Carragher's Best XI; there's even a list of Chelsea-West Bromwich from 2011. Needless to say, most of these memorabilia come from the British leagues and, of all of them, those of Chelsea (who then continued the tradition with fantastic match programmes on Instagram) and those of the English national team, of which there are many antique copies, are among the most sensational. Today, in the Premier League and in the minor leagues, from the top clubs to the provincial ones, many clubs still sell their dossiers in front of or inside the stadium and you can even subscribe to them.

This demonstrates that some forms of publishing still manage to survive, but it is, above all, a British phenomenon. For Italian teams, by now, digitization has taken over - and it must be said that the Match Program has never really been of great interest to clubs. Sure, getting to the stadium by car and reading the match program directly from your smartphone is very convenient. But when you get home afterwards, you actually feel more empty of something.