Knitwear Football: the story of knitted football shirts in Italy

When the material of the kits unites the Napoli of Diego and Tyler, The Creator

March 30th, 2021

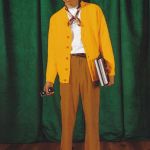

In the latest fashion weeks we have witnessed a resurgence of knitwear in both menswear and womenswear collections. Not only historical brands like Prada have made knitwear a cornerstone of their most recent runway shows, but also independent and up-and-coming ones like Vitelli and Paura, to mention a few, have brought back cardigans, jumpers and vests knitted in fabrics such as mohair wool. Whether in the vintage market or in that of crochet clothing sprung on Instagram during the pandemic with brands like Rathat, knitwear has been spreading through underground fashion for a few years now. Also embraced by rap artists like Tyler The Creator as well as by the skating culture, knitwear is once again back to being the link between haute couture and sportswear.

Afterall, the world of sport has been the first important stage where knitwear became part of popular culture, determining its double nature as both casual and sportswear. Other than cyclism and golf, football is the main example of this legacy, especially in Italy. From Napoli and Fiorentina iconic NR kits to those designed by Kappa for Juventus, knitted wool has dressed (and drenched in sweat) some of the greatest stars from the post-war years to the Eighties.

Prior to the turn represented by the improvement of synthetic fibres, knitwear and twill cotton were the epitomes of sportswear fabrics. Think of how Slazenger V-neck jumpers were simultaneously worn on greens by golfers - including Sean Connery in the famous match framed in Goldfinger - and by Her Majesty’s footballers in their free time, hence covering the role that is now assigned to tracksuits.

At the roots of the term "jersey" used to refer to football kits lies, in fact, a machine stitching technique for wool and cotton fabrics. Being football born as a winter alternative to the game of cricket, since its beginnings shirts were made of knitted wool, with crew necks and slim cuts that made them fall right on the waist; exactly like knitted t-shirts, like those that have recently resurfaced in the fashion industry, are still designed these days.

If in England manufacturers soon opt for heavy cotton mixed with synthetic fabrics, Italy - with its sartorial excellence - makes abundant use of knitwear on football pitches. Vicenza wool factory Rossi is possibly the most famous example of this trend, responsible for setting up a dialogue between sportswear and casualwear. However, there also are the cases set by the Milanese Maglificio Vittore and by Maglificio Lama in Perugia (Milan, Inter Milan, Fiorentina, Genoa, Sampdoria, Cagliari are just some of the clubs equipped); not to mention many other local manufacturers whose names are lost in the ranks of Italian football, in days when the logos of technical sponsors were still banned from shirts.

Wool came in blends with threads of early synthetic fabrics like Terytal - that helped to increase the garments' elastic properties and to avoid their felting - in percentages that varied according to the season. The Napoli 1988-89 NR shirt is an example of this. There were, in fact, two versions of the same kit: a traditional woolen one for the winter and a lighter summer one in Rayon-style shiny synthetic fabric.

The necessity of innovative kits led to the landing of Umbro in Italian football. The British brand, between the mid-60’s and the following decade, represented an international avant-garde in matters of sportswear design, both esthetically and technologically. Think, for instance, to the kit made for Sunderland beginning from the 1977-78 season, with its vertical stripe pattern weaved using the jacquard technique.

English brands like Umbro and Admiral are, in fact, among the firsts to understand - starting from the 1959 Umbro Set - the potential of the replica kits, hence contributing to normalise the use of jerseys, albeit limited to kids sizes, also outside of football grounds. Similarly, Italian department store chain Upim released on the market a series of kits including knitted shirts, shorts and socks - although not comprising the clubs’ crests - of some of the main Serie A teams.

The liberalisation of the use of technical sponsors on the shirts of italian football teams starting from the winter of 1978, alongside the advent of colour television, finally contributed to bringing also to the Belpaese the wave of innovation that Admiral had introduced British and European football to since the beginning of the decade. Following the example set by the likes of Admiral, Umbro, adidas and Puma, we witness a decrease in the number of manufacturers flirting with football in favour of brands exclusively dedicated to sportswear. From this moment on, sports clothing and design begin to take a more authentic and delineated route.

A series of both new and existing brands - like Kappa, Superga, Pouchain, NR, Tepa, Tiko, and Mec, among others - take over the more traditional wool manufacturers, beginning a successful period where knitwear acquires a new consciousness in matters of brand identity and innovative chromatic solutions. The fabrics employed are responsible for shirts characterised by neat silhouettes and dense volumes, further enhanced by small yet vibrant details like spear collars mounted on V or slightly rounded necks, through which vests and golden rosary chains peek; geometrical logos with a modernist attitude; and crests, numbers and sponsors first hand and then machine-stitched. Many are the examples, from the NR Roma kit sponsored by Barilla, to the sophisticated blue-and-white elasticated jacquard fabric hems designed by Umbro for the 1979-80 Brescia kit, whose official technical sponsor was actually Tepa. From the 1971-72 Monza kit featuring numbers futuristically stitched on the sleeves and the NR Avellino shirt with its Ajax-style black-ribbed green centre strip, to the Misura-sponsored jersey Mec designed from 1981 to 1985 for Inter Milan, featuring the iconic biscione scudetto stitched, depending on the season, either on the left or right sleeve.

The latest achievements in matters of jacquard looms helped to work on more complex patterns responsible for shirts like those made by NR for 1983-84 Fiorentina, 1983-84 Pescara, and the 1982-83 Lazio "flag" jersey, that featured printed numbers. This nonetheless represented football’s incoming synthetic future and the imminent decline of knitwear.

Despite the progressive decline of many glorious provincial Italy brands that occured with the rise of synthetic fabrics and international giants like Nike and adidas, over time knitwear still succeeded to impose itself within pop culture. Woolen kits, with their fitting similar to that of knitwear garments, alongside sober yet iconic designs, have managed to acquire a new relevance in the field of casualwear. Think, for instance, to how Lyle&Scott and Lovers FC have recently reimagined a series of classic kits in a knitwear and streetwear perspective, or to Colin Firth sporting the Arsenal 1970-71 shirt in the famous film Fever Pitch.