What we mean when we talk about sustainability in fashion

A conversation with Francesca Romana Rinaldi

December 18th, 2019

Sustainability. This is the word that has marked the fashion industry over the last twelve months. Overrated, abused, full of different meanings, the term defines the effort - often belated - that brands and industry players are making to become more eco-friendly. The focus on this kind of issue is now widespread among big brands, but especially among consumers. Lyst's Year in Fashion 2019 report also shows that research on sustainability issues has increased by 75% on an annual basis, with an average of 27,000 searches per month.

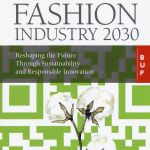

Francesca Romana Rinaldi, university professor at Bocconi University, has always been interested in sustainable fashion, well before it became a trend. In her new book Fashion Industry 2030. Reshaping the future through sustainability and responsible innovation, the author collects the voices and statements of the major players of the industry, which tell what can be done to dress and shop in a sustainable way. There are already many good examples and the companies' approach is gradually moving away from greenwashing to become truly strategic. The book presents many of these positive business experiences, but also the main findings of more than 50 interviews with opinion leaders, entrepreneurs, CEOs, managers, organizations, policymakers, some of which were shared during the event.

During the presentation of the book at the Patagonia store in Milan, Rinaldi took us through the complicated and insidious world of sustainability, very often the topic of brands' positive statements hiding greenwashing habits. Rinaldi immediately emphasizes the importance of using the right communication when dealing with these kinds of topics:

It is very important we approach the problems of the fashion industry starting from data, we need a scientific perspective. What I tried to explain in the book, which is what I often talk about during my lectures, is the fact that we must try to use a multi-level method: not all consumers are interested in the same way and not all consume in the same way. Not everyone considers sustainability as a fundamental factor, not everyone is radical. There are many consumers, I call them fashionistas, for whom aesthetics is still the key element that drives shopping. It is essential that we try to educate different types of consumers and readers in the right way.

A first step could be the awareness of consumers about the environmental cost of what they buy, for example, a simple pair of jeans.

Up to 10,000 liters of water are used [to make a pair of jeans], considering the water needed to produce the cotton, to make the product, and the water the consumer uses to wash the jeans. But then we also need more detailed information, which shows what really happens in the supply chain.

While Lyst's data already showed consumers' response to environmental issues, the Getting Woke section of The State of Fashion 2019, a report by BoF and McKinsey&Company, reveals that nine out of ten consumers of the Generation Z believe that big companies have a responsibility and a commitment to take action on the most important social and environmental issues of our time. It's a landmark change, and it's not just thanks to Greta Thunberg.

There is certainly more interest. This is happening because there are information channels, such as social networks, that act as megaphones for information that in the past was not shared so powerfully and not by so many people. Peer to peer sharing really can make a message viral. The case of Greta is the best example of virality. It's also a matter of media and social networks.

It is no coincidence that Rinaldi almost immediately names Patagonia, a brand that has always been synonymous with environmental sustainability, a B-Corp that makes an environmental commitment one of its driving forces. The company is well aware of the costs and difficulties that such a decision involves.

There are not many companies that are activists, as is Patagonia, so I believe that the success of brands like Patagonia lies in the fact that it is able to create engagement for the consumer, for friends, for those who love the brand. They are log marks because they use the same language of the community. In particular, in the case of Patagonia, they are nature lovers, people who have respect for nature in their DNA. In my opinion, the secret to success is precisely this.

However, how would it be possible for brands to make a radical turnaround and become real sustainable brands?

I hope it really will happen and that we don't have to wait until 2030 for this radical transformation. There are brands like Patagonia that have already undertaken this radical transformation years ago, others that are just starting to approach. There are still examples of green washing, examples of companies that have not yet restructured their environmental processes to move towards circularity, for example. The path is long and complex. It is also true that it is the only possible path. The costs of sustainability are there, even in the various videos of Yvon Chenard in which he says that sustainability actually has a cost. Patagonia is not the only proof of this. Many companies say so, such as Candiani, who worked with Dondup on an innovation in the supply chain that, however, requires an investment in research and development. The cost of one type or another, depending on the value chain and the business model, is a necessary cost. It should not be considered a cost but an investment for the sustainability of the competitive advantage on a long-term basis, if you do not do this you will not survive.

Someone calls 2019 the year of awakening, twelve months in which it has become essential for every company, even in the world of fashion, to satisfy the increasingly urgent demands of consumers for transparency and sustainability. If these requirements are the basis for the development of start-ups and small companies, for the big ones the process towards the eco-conscious renovation is not so simple, and above all, it is not so fast. However, it is now clear that a more sustainable future for fashion is not only possible, but it is also necessary. Everyone has realized that the companies that will be successful will be those that combine aesthetics, ethics and responsible innovation. Kering Group is trying to do this, and by 2025 it has planned to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 40%, while LVMH is reducing its packaging by 60%. But taking an active stance on social issues, satisfying demands and often changing sources, production methods, mentalities or even identities to adapt to the needs of the planet and simultaneously win over new generations of customers is not something that can happen in a short time. It requires costs, efforts, time.

The book by Francesca Romana Rinaldi reminds us and emphasizes the importance of educating consumers who must be aware, involved and informed. There is still a long way to go if, as a recent Swg research that asked Italians to mention some truly sustainable brands, 77% of the interviews were unable to name a brand. Maybe 2019 was the year of the awakening of our eco-awareness, but what will be the year in which we will see the first real results of this call for sustainability?