Who do works of art really belong to?

A lawsuit filed against Maurizio Cattelan has reopened the diatribe between artists and artisans

May 6th, 2022

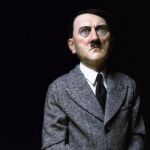

This week, Artribune reported on the story of Maurizio Cattelan and Daniel Druet. Druet is the French sculptor who has materially realized works such as The Ninth Hour (1999) and Him (2001), which respectively portray John Paul II and a surreal version of Hitler, yet his name did not appear in any of the catalogs where instead, as the total author of the works there was only Cattelan. Now Druet wants 5 million and has sued Cattelan himself, gallery owner Emmanuel Perrotin and the Musée Monnaie de Paris, which in 2016 hosted the exhibition Not Afraid of Love. «He would send a ten-line fax or his Italian co-workers, who barely spoke French, would give me instructions. Everything was always very vague and it was up to me to manage it», recounted Druet to Le Monde, on whose pages he said he had been engaged for four years in a battle against «all those artists who use the work of others to promote themselves». To make a long story short, this is the issue: Cattelan commissions to Druet a dozen hyper-realistic sculptures that the sculptor realizes at 33,000 euros each, the statues are then exhibited with complete attribution to Cattelan who resells them for millions and millions. In the meantime, no one talks about Druet, who materially made those works, also deciding many aspects and details.

At the time when the agreement between the two was made, the terms were very vague, the copyright contracts did not yet exist, nor apparently did the gallery owner and artist care to give credit to Druet who found himself, in his own words, in «the humiliating role of the modeler» and which aroused a feeling that is as simple as it is unsettling in a contemporary art world in which artist and maker are two increasingly distant figures: «An unrealized idea is worth nothing», said the sculptor to Le Monde, «and without me Cattelan can do nothing». The most paradoxical thing is not only that Druet was not even invited to the exhibitions where the works were displayed, but that those same works bear Druet's signature engraved on their surface. «Academic merit versus design genius, we're dealing with two virtuosos belonging to two different universes, it's exciting» commented the director of the Palais de Tokyo, Jean de Loisy. According to the gallery owner Perrotin, if Druet loses, the law will protect the artists «against the abuse of power by manufacturers» while if he wins «all artists will be attacked and it will be the end of contemporary art in France». The case, by De Loisy's own admission, is quite intriguing. The problem for Druet will be proving that he has infused his own personality into the various works, given how Cattelan was involved in their conception and display down to the last details. «This trial will demolish a myth», said Druet. «The artist who never touches his work and who is acclaimed by the world is finished».

Regardless of how the case evolves (the trial date is set for May 13), Druet's lawsuit exposes a problem that goes well beyond art and touches the entire design world - including fashion. For too long now there has been a division or compartmentalization that has seen the creative person lose contact with the material of his or her works with a role that is increasingly abstract, self-referential and philosophically opportunistic. Through conceptual acrobatics of all kinds, artists justify their distance from technical expertise - yet a painting by Picasso would not be as valuable if Picasso had had someone else paint it by giving him instructions over the phone. On a level of banal intuitive logic, the work has value because it was created by the artist. Yet today it seems that the artist is only a creator who cannot lower himself to come to terms with reality, and whoever does not appreciate this is a retrograde who has remained stuck in the past, with the Impressionists and their en plein air canvases. And this only increases the distance between the public and art itself - especially if the names of the makers, modelers and actual creators of the objects we see are hidden behind the scenes, in anonymity.

Something similar happens in the field of fashion where, for example, it is not unusual to find creative directors who lack the most elementary notions of tailoring, whose work is limited to an impalpable "vision" and to the work of extensive research and design teams. And while it is true that the work and the figure of the creative has changed a great deal in recent years, the rhetoric about attributing the entire creative work to a single designer-demurge remains. The cult of creative directors is necessary, even when they have so many declared collaborators that it is not clear what role they have played in the success of such a collective work. Yet to imagine a creative director increasingly detached from the final product seems counterintuitive: fashion was born precisely because a certain clientele wanted their clothes to be made by a certain professional who was better than the others - a relationship with clear logic. Today, the creative director carries out a job that is much less hands-on, focused on communication, on concepts as well as on the collections themselves - a progressive abstraction that distances the creator from the executor. In this growing distance there is a concreteness and authenticity that is being lost.

This is not to say that the current way in which fashion works is wrong, but that when the creative person moves further and further away from the materiality of his or her works (i.e. from reality), the artistic weight of those creations also begins to diminish. If the creative director conceives the collection but others design the individual items, who should be credited with the design? When it comes to Alexander McQueen, a genius in his field, many emphasize that his great ability was to know how to manipulate the material, to know how to take needle and thread and build a couture dress himself, which makes his clothes much more precious and valuable. The same can be said of an entire generation of couturiers, from Cristobàl de Balenciaga to Yves Saint Laurent, who before designing entire collections possessed the practical know-how that would allow them to create a certain garment by grasping needle and thread in person. Empires were founded on those technical skills. Will we tomorrow be able to found equally long-lived empires without that necessary connection of academic merit and design genius that Jean de Loisy defines as belonging to different universes?

And even though we live in a post-modern world, where Duchamp cleared customs almost a century ago of the concept of the ready-made, the circumstances of today's society are leading to a re-evaluation of the role of the "technician": if the fashion world has resumed reminding its clientele of how handbags and shoes are handcrafted, or if in certain cases design teams have gone bow to bow instead of the individual creative director, it is precisely because the public has begun to be less and less persuaded by the rhetoric of press releases. Once again, we are not invoking here a return to the mythical origins of art and craftsmanship, an idealistic and unfeasible vision, but a reunification of the roles of the pure creative and the pure craftsman. The risk, otherwise, would be that of finding ourselves in front of a generation of creatives who are increasingly vacuous, lacking in skills that can be expressed in the physical world and detached from reality, in which the exercise of art is limited to the production of an intangible fantasy that, however, doesn't translate into an actual object through comparison and technical knowledge of reality. In a world of creatives, where are the artists?