Givenchy's marketing problem

Celebrities have power, but hype can't be manufactured

October 20th, 2020

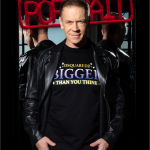

Over the past weekend, half the world's Instagram feeds have been flooded with a shower of stars wearing total looks from Givenchy's latest SS21 collection designed by Matthew Williams. A roundup consisting of Travis Scott and Kylie Jenner, J Balvin, Kate Moss, Naomi Campbell, Alton Mason, Skepta, Kaia Gerber, Kim Kardashian, Bella Hadid and all that round of well-known and lesser-known faces (which also includes Williams himself) that are part of the brand's friends & family. Resorting to mega-influencers and famous actors is now a bit of a common practice of all luxury brands but with this project we are (unfortunately) far from iconic moments such as the appearance of Adrien Brody, Willem Dafoe and Gary Oldman on the Prada catwalk, back in 2012. Givenchy's social strategy was not born with the intention of associating pop culture faces with the value system of its brand but instead has the air of a generic attention-grabbing stunt to take advantage of the more momentary and superficial aspects of celebrity marketing. There is only one problem: the hype is born, it is not created.

This episode is one of the most obvious examples of how a certain side of the fashion industry is trying to artificially reproduce the hype – but the hype is a social phenomenon that comes from below, from the street and cannot be imposed unilaterally from above without consumers not noticing. Givenchy's campaign (but is it a campaign?) is not interested in aesthetics or storytelling: it is just a violent frontal attack on the attention of the consumer whose final result is paradoxically bland, lazy and forced at the same time. Bland because there is a lack of history and art direction: it all boils down to a bunch of superstars dressed in very expensive clothes – that is, the daily bread of anyone with a profile on Instagram. Lazy because there is no desire to create a culture or aesthetic but the protagonists of this non-campaign seem to have been chosen only based on their number of followers and given carte blanche, with clearly sub-standard, blurry or (worse) banal photos. Forced because such a huge deploy of celebrity makes one assume an excessive need for attention for a brand and a creative director who, in themselves, have all the visibility they deserve and even more.

Perhaps if the protagonists had been two or three instead of fifty (sic!) and if the social initiative had been gradual over time there would have been nothing to complain about. After all, as has been said, resorting to celebrity marketing is a bit of a common practice for luxury brands – but it's also an art that requires subtlety, calculation, timing. Take, for example, the Jacquemus phenomenon, a true modern touchstone of a brand's social success: the hype created around Jacquemus is, for better or worse, the result of a patient and organic strategy, careful timing and a very measured recourse to Bella Hadid's star power, made the official face of the brand in surprising campaigns and parades without excessive fanfare. But if, before his mainstream fame, Jacquemus's Instagram profile was almost a moodboard of his designer, a visual diary that is now even sold as a photo book in its own right, Givenchy immediately went all-in with the star power, playing its cards all at once, immediately betraying his true intentions: to sell.

Riccardo Tisci had injected new life into Givenchy veins, a maison in historic identity crisis as Alexander McQueen once said in one of the most abrasively honest outings of his career. And Tisci, let's face it, had revitalized the brand with a new aesthetic for its times but, ultimately, aged not very well (the t-shirt with the rottweiler, the stars everywhere, the logo hoodies in all the provincial boutiques are the greatest hits of his career) but they were other times, still the market was not saturated with streetwear products and at least there was the air of novelty.

And after Clare Waight Keller's sleepy interregnum, Williams was supposed to restore lustre to the old house – her debut collection worked, mostly, though there was room for improvement. And this collection should have settled more in the collective unconscious before being flaunted without the slightest grace as it just happened. But, apparently, everyone who counts wears it now. We are curious to wait for the way the brand will try to top itself when the collection comes to stores: it is difficult to imagine a campaign so over-the-top as to erase the memory of this.